Nancy Holt’s System Works: A Reflection on Research

My 2004 dissertation, Nancy Holt and the Sculptural Lens, was intended to be a comprehensive overview of Holt’s artistic production. The goal was to present “an in-depth study of Holt’s oeuvre, organized thematically around her admitted focus on perception,” illustrating “the myriad and increasingly complex perceptual layers Holt has explored throughout her artistic career, as well as the manner in which her work reflects a wide array of the artistic concerns central to the period in which she was working.”1

I devoted an entire chapter to Holt’s System Works, which she began producing in the early 1980s. These installation and site-responsive projects referenced resource delivery—specifically heating, electrical, drainage, plumbing, and ventilation systems. In thinking about these works at the time, I noted that,

Though aesthetically the works vary greatly, based on the specific parts and mechanics needed for the variety of systems involved, they are intimately related in their thematic intentions. Through them, Holt attempts to focus attention on devices that are considered critical for modern-day life, but that we tend to ignore, take for granted, and even disown. 2

My interpretation of the systems works relied heavily on Holt’s own description of her intentions:

The sculptures are exposed fragments of vast, hidden networks, they are part of open-ended systems, part of the world. Over the years these technological systems have become necessary for our every-day existence, yet they are usually hidden behind walls or beneath the earth and relegated to the realms of the unconscious. We have trouble owning up to our almost total dependence on them. 3

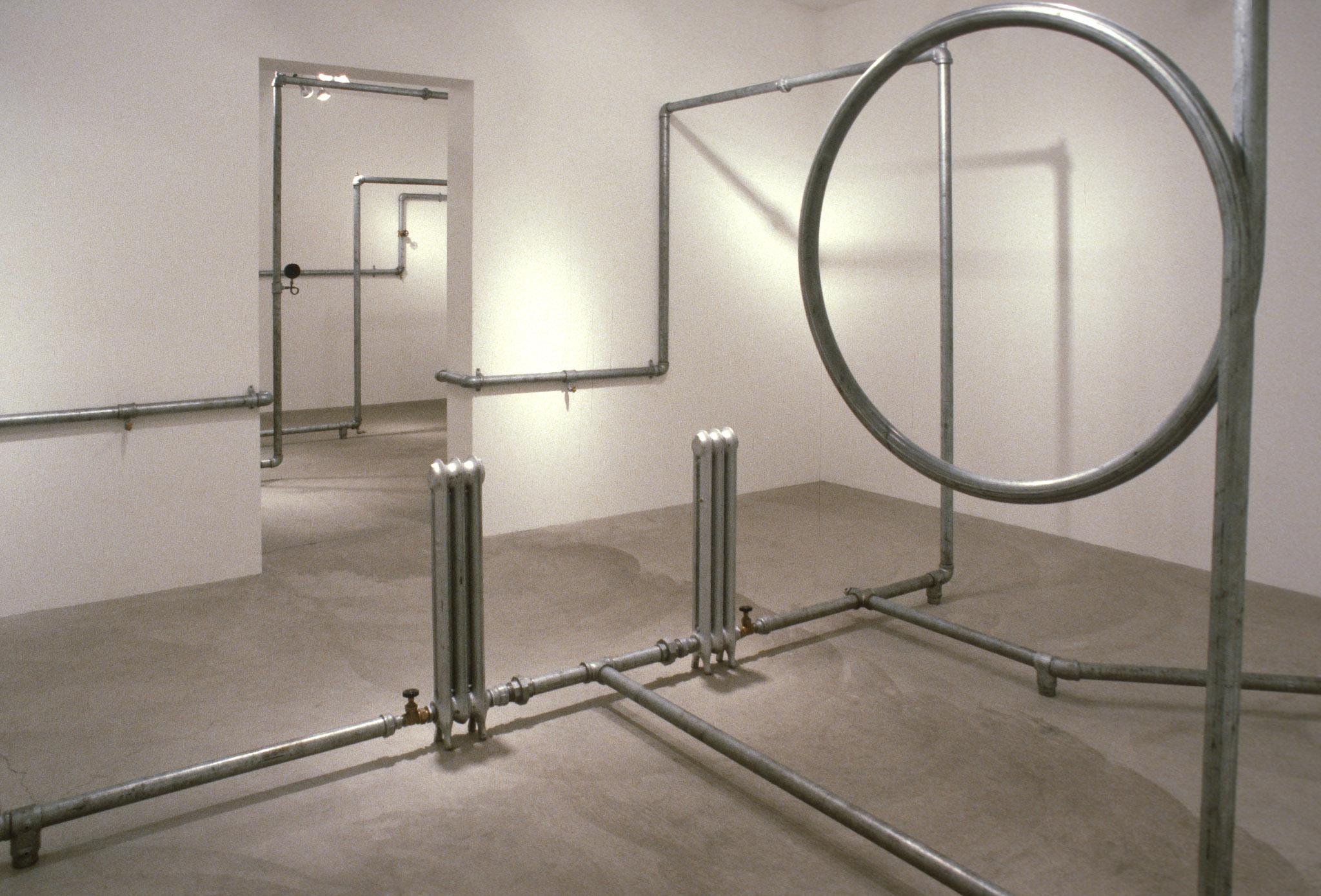

In discussing gallery installations such as Heating System (1984-85)—first presented at the John Weber Gallery in New York City with the title Hot Water Heat, and secondly at Flow Ace Gallery in Los Angeles with the title Flow Ace Heating—and public art projects including Catch Basin (1982), I emphasized the formal details of the works, highlighting that Holt typically utilized the hardware of a particular system—piping and conduit, valves, gauges, sockets, radiators, basins—and then multiplied it profusely. The system continued to be functional, providing light or water or heat or air movement, but the way that the work grafted onto it ensured that viewers observed and interacted with it in a more mindful way. Holt’s intention seemed to be primarily about awareness and understanding of the largely invisible structures that provide physical comfort in our built environment. Holt expanded our perception of the world around us by making it visible in new, aesthetically and physically compelling ways.

In the more than twenty years since, I have come to understand the value of Holt’s artistic practice quite differently. Previously, I particularly appreciated her art as a “snapshot” of the time and place in which she was working. The breadth of her practice seemed to sum up the complexity and messiness of ’70s and ’80s art. Her work was especially timely in that she was working in so many realms simultaneously— installation, public art, video, book art, photography—in the “pluralist era” of Postminimalism. 4 My interpretation today has shifted considerably, as the view from the 2020s, and my contemporary lived experience, provides a very different context in which to see Holt’s art. The System Works in particular now lead to environmental considerations that do not seem to have been her central intent at the time of their creation. However, thinking about these projects from a contemporary environmentalist point of view deepens their meaning and significance, and further highlights the importance of Holt’s artistic contributions. 5

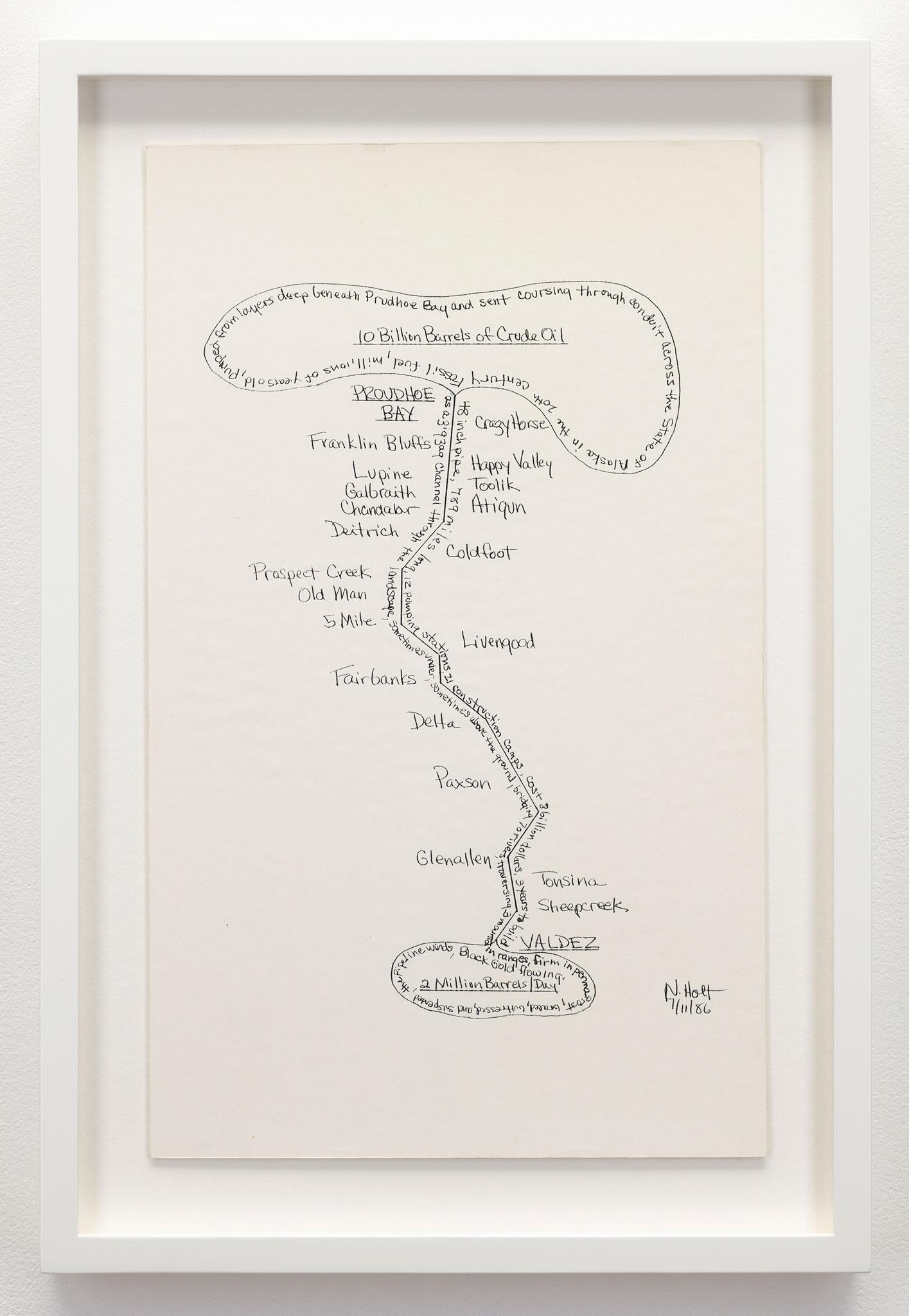

This is not to say that ecological ideas were completely absent in Holt’s mind as the works were being conceived and executed. However, such concerns do not seem to have been meaningfully embedded in her overall practice. She spoke sparingly about environmental ideas, and only most significantly in relation to Pipeline (1986) and Sky Mound (1984–). Pipeline, which was installed at the Visual Arts Center of Alaska, in Anchorage, evidenced an environmental theme that was clearly driven by Holt’s attention to the work’s site-specificity. Rather than referencing general supply or elimination systems, this project unambiguously referenced the Trans-Alaska Pipeline for crude oil. Holt stated, “The Trans-Alaska Pipeline, relentlessly snaking in and out of the ground, spanning rivers and traversing mountain ranges as it channels dark primordial fuel through the frozen landscape from one end of Alaska to the other, became the impetus for the making of Pipeline.” 6

Pipeline was a particularly elaborate System Work, with both outdoor and indoor elements. As it snaked around the art center’s building, it appeared to emerge from and then penetrate the earth. The piping pierced an exterior wall, meandered within the gallery space, and eventually dripped oil onto the floor. Overall, the piping echoed “the vast scope and interplay of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline’s visual inclusion and intrusion on the landscape,” and “while not directly functional, points to an elaborate eight billion dollar system that has twelve pump stations, eight hundred miles of pipe, and ten billion barrels of oil. Oil slowly drips from one section of Pipeline, pooling in a puddle on the floor, thickly black against a stark whiteness, like the snowy background of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.” 7 Holt’s description explicitly suggests an oil spill in the pristine Alaskan wilderness. Here, and as in all the System Works, Holt asks us to look deeply and actually see an existing system. However, the emphasis here is not simply on perception. It is on the potential failures of that system, and the grave ecological impacts such a failure would produce.

Had it been completed, Sky Mound would have converted 10 million tons of decomposing garbage on a 570-acre landfill in the New Jersey Meadowlands into the largest artwork in America. 8 Sky Mound would have served as a gigantic System Work, visually accentuating and enhancing the site’s landfill-capping technology with thoughtfully placed vents, methane flares, ponds, pathways, and viewing mechanisms. This location provided Holt with an entirely new type of system to engage with, and one that naturally called to mind environmental issues. She noted that “seeing the landfill makes one strongly aware of our role in changing the natural environment, and will increase awareness of the complicated problem of what we do with our garbage.” 9 Sky Mound’s location required Holt to explore the forms and processes of a waste management system, which necessitated engagement with ideas around environmental impact and ecological concerns. As with Pipeline, Sky Mound explicitly brought these issues into play in ways that are not clearly present in the other System Works, but they appear here because the particular site expanded Holt’s own perception into this eco realm.

Environmental issues were really only beginning to come into focus in the 1970s and 80s. Concerns about acid rain and holes in the ozone layer, which were terrifying in their own way, seem almost quaint compared to the radically dangerous world we experience today. Climate change, rising sea levels, biodiversity loss, drought, extreme weather, and deadly wildfires threaten everything from our global food supply to coastal population centers around the world. The unequal social impacts of these issues call attention to extreme wealth disparities and social injustice globally.

A viewer experiencing a work such as Electrical System in 1982 was likely awed by its aesthetics, with its plethora of conduit and abundant glowing light bulbs filling the gallery setting. Those unfamiliar with the actual hardware of electrical lighting no doubt gained new awareness about how light is technically delivered when you flip that light switch on the wall. I suspect I was not alone in having a very different experience viewing the work at the Locating Perception exhibition at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles in late 2022. Seeing Electrical System there, I felt a sense of discomfort. Though intensely beautiful, it also read to me as an almost cavalier overabundance of light—so much electricity! So much waste! The installation incorporated contemporary standard materials in its construction, which today means greater efficiency—LED rather than incandescent bulbs, for example—but I still felt uneasy reveling in the formal beauty of the excess electrical material on display. An early twenty-first century aspect of perception in Holt’s work? Eco-guilt.

The pressing environmental problems of today require an all-hands-on-deck response. Everyone, including artists, has a role to play in helping find the solutions we need to protect our world. Holt herself stated that “Technic in Greek means ‘art or artifice.’ The land drainage systems of Crete and Babylon, the aqueducts of Rome are art in their own right. Technology and art don’t exclude each other. By seeing the aesthetic aspects of our basic technologies and bringing art to bear on the construction of future systems, a new technicology can develop.” 10 Further, she explained, “What I’d like to see is artists being involved in planning the world visually. We’re the experts and we’re never consulted about the world around us and how it looks.” 11 Holt did see her work as contributing to the betterment of our built environment, though she seems to have focused on making our systems more aesthetically meaningful. I would argue that seeing her works today can do even more. The perceptions they engender now go beyond the visual and into a desire for action.

Successful art gives on a multiplicity of levels—general visual interest in the work’s physical form, conceptual interest carried through the intent of the artist in creating the piece, and contextual significance as it reflects the time and place of its creation. I have come to believe that the most successful art gives even more. Art that deepens in meaning over time, in ways that the artist might not have even considered, is to me a hallmark of truly great work. That we as viewers many years removed from the point of original creation can find new meanings and relevancies—content that speaks to our current time and place—reflects a work of art that evolves and maintains significance. Holt’s original intention with her System Works was to make us see and understand the world more deeply, and I believe they do so now in an even more heightened way. New questions arise, new feelings are generated. This strikes me as a true marker of what the very best art does over time.

Afterword

I began to research Nancy Holt in 1997, while I was a graduate student at Rutgers University. One of the requirements of my doctoral program was a written qualifying exam consisting of a twenty-page research paper completed over the course of ten days. The prompt asked me to discuss the contribution of women to public art since the 1970s. Holt was the first artist I thought of. I’d been introduced to her work in my “Intro to Twentieth Century Art” class in college. Back in the early 90s, we’d looked at Sun Tunnels (1973–76) and Dark Star Park (1979–84), both of which were illustrated in my Modern Art survey text. These institutional structures—college lecture, college textbook—“told” me that Holt was an important figure, and so she seemed a natural choice for my ten-day paper. I was shocked on the first day of intensive research for that exam, when I searched the Rutgers art history library and discovered that there was no book focused solely on Holt’s work. For someone whom I understood to be so significant, this was astonishing. I decided on that day that my dissertation project would be a comprehensive study of Holt’s art and her contributions to late twentieth-century American art.

I ultimately conceived of the dissertation as a sort of baseline reference tool for understanding Nancy’s work. I strove to present an overview of everything, including detailed specification information on as many of her projects as possible. I was so lucky to be able to speak with her in person as I began. Not only did she answer my many questions, but she was also incredibly generous and helpful in getting me the materials I needed. The John Weber Gallery had just officially closed its doors but was still holding the bulk of her archival materials. Nancy contacted them and ensured that I was able to read all of those files. She vouched for me and helped me gain access to the video works and documents held by MoMA in New York. She directed Video Data Bank to loan me (free of charge—key for a poor graduate student!) the works they held in their collection. She even offered up several large three-ring binders stuffed with a generous portion of her 35mm slides, which I was able to digitize and use for my project. All of this allowed me to create what was, at that time, the most comprehensive overview of her art to date. In addition to my text, which unified her varied art production under the idea of perception, I developed one appendix listing all of her works and another outlining her exhibition history. The bibliography included every article, review, exhibition catalog, interview, and book mentioning Holt that I’d uncovered in the ten years I’d spent researching her.

While I suppose I’m not alone in looking back on my dissertation with a certain amount of mortification (how could I have missed all those typos?), I will always be proud to have produced a useful research tool for others. My thesis, that “Holt’s work provides an illuminating lens through which to examine American art from the late 1960s through the 1970s and 1980s,” 12 was certainly not earth-shatteringly original, but I do believe that my attempt to address her work in its entirety, from the earliest projects more about strictly visual interests, to later works exploring perception in more conceptual ways, was significant in shining light on her art. I was successful in achieving my objectives: “to reveal the provocative and fascinating nature of Holt’s work, to illustrate what makes her such an important contributor to sculptural practice at the end of the twentieth century, and finally to give her the credit that I believe she is due.” 13

By the time I had completed the dissertation in 2004, I was too depleted to undertake the work necessary to turn it into an actual book that anyone would be interested in reading. I held quite a bit of low-grade guilt around that decision, as I still felt strongly that Nancy’s work was important and fascinating and that more people should know about it. I was beyond thrilled when I was contacted in 2008 by Alena Williams, who was working on what would become Nancy Holt: Sightlines. Alena asked me to contribute a chronology for the book, which I was honored to do. To be associated with the first published monographic study on Nancy’s work was such a privilege and a fulfillment of my deep desire to celebrate her and her art.

For me, though, even more exciting than the book was the exhibition organized in conjunction with its publication. I traveled to New York to see Nancy Holt: Sightlines at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in 2010. In my years of research, I had visited almost all of Nancy’s extant public art projects, but I had seen almost none of her work in a formal exhibition setting. I’d read countless ’70s and ’80s gallery reviews and seen many historical photos of exhibit installations, but it was exhilarating to actually see her work—an entire exhibition devoted to it!—in person. It felt as if something had finally, fundamentally shifted in terms of the appreciation of her art.

And has it, indeed! Holt/Smithson Foundation’s efforts since 2018 have ensured that Nancy Holt, and particularly the wide breadth of her production, is now visible on a global scale. This has no doubt introduced her to new audiences, but it also inspires those like me who may have known her art primarily through reproduction. I found visiting the Locating Perception exhibition at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles in 2022 especially moving. To look through an actual Locator? To see photographic projects that I’d only glancingly read about? And especially, to be engulfed by an installation of Electrical System (1982)? I actually cried as I meandered through the conduit, bathed in the glow of Nancy’s light. My understanding of that work, and of her art overall, was profoundly deepened by that experience.

I look forward to many more opportunities for engaging with Nancy’s work in this way. I genuinely believe that she has important things to say, even beyond what she consciously intended as she was creating her work. The System Works, in particular, are deeply relevant for our time as they help us think critically about natural resources and the health of our environment. I thank Nancy not only for the creation of such rich, thought-provoking art but for her foresight in establishing the Holt/Smithson Foundation —that it may continue to share her with us.

Author biography

Julia L. Alderson is a Professor of Art History and Museum Studies in the Department of Art + Film at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, in Arcata, California. Her specialization is in the area of American and European art, 1860 to the present. Her research interests include topics in sculpture, public art, and Land Art, as well as museum methodology and theory. Her publications include "Chronology," for Nancy Holt: Sightlines (University of California Press, 2011), and "A Temple Next Door: The Thomas Kinkade Museum and Cultural Center," for Thomas Kinkade: The Artist in the Mall (Duke University Press, 2011).

Selected bibliography

Alderson, Julia. “Nancy Holt and the Sculptural Lens.” PhD diss. Rutgers University, 2004.

Holt, Nancy. “Notes on Ventilation Works.” May 19, 1992.

Oakes, Baile, ed. Sculpting with the Environment: A Natural Dialogue. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995.

Gelburd, Gail. Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993. Exhibited by Council for Creative Projects, NY.

Perreault, John. “Holt’s Volts.” Soho News 2 February 1982, 24.

- 1 Julia Alderson, “Nancy Holt and the Sculptural Lens,” PhD diss, (Rutgers University, 2004), 30-31.

- 2 Ibid, 71.

- 3 Nancy Holt, “Notes on Ventilation Works,” May 19, 1992, 1.

- 4 Corinne Robins’ book The Pluralist Era was central to my thinking at the time. See Corinne Robins, The Pluralist Era: American Art 1968–1981, (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1984).

- 5 Holt herself retrospectively considered these issues as they pertained to her work in a 1993 untitled statement in Gail Gelburd’s Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993), 34. See the reprint on the occasion of the exhibition Nancy Holt: Circles of Light at the Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany here.

- 6 From Nancy Holt, Michelle Stuart: Alaskan Impressions, exhibit at The Visual Arts Center of Alaska, Anchorage, Anne Lingener-Reece, curator, July 22–August 22, 1986. No pagination.

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 Descriptions of the work are available from a variety of sources, including Douglas C. McGill, “Jersey Landfill to Become an Artwork,” New York Times, September 3, 1986, C1; Terry Ryan LeVeque, “Nancy Holt’s ‘Sky Mound:’ Adaptive Technology Creates Celestial Perspectives,” Landscape Architecture 78 (April/May 1988): 82–86; and Nancy Holt, “Sky Mound,” in Sculpting with the Environment—A Natural Dialogue, ed. Baile Oakes (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995), 61–63.

- 9 Alderson, “Nancy Holt and the Sculptural Lens,” 228.

- 10 Nancy Holt, “Notes on Ventilation Works,” information sheet, 2.

- 11 “Artist Nancy Holt Completes Star-Crossed,” The Miamian, July 24, 1980, 1.

- 12 Alderson, “Nancy Holt and the Sculptural Lens,” 30.

- 13 Ibid, 30–31.