Nancy Holt’s Sky Mound: “The exposure is better than at the Met”

Every time I travel from Strasbourg, where I live and work, to Princeton, where I go for research, I fly from Frankfurt to Newark and then drive to my destination. The landscape is made of highways, parking lots, office buildings, motels, and occasional vegetation, but nothing stands out and invites one to pause. Nancy Holt’s unfinished Sky Mound (1984-1991) was meant to catch the eye, provoke awe and tear the texture of suburban New Jersey by its stunning difference.

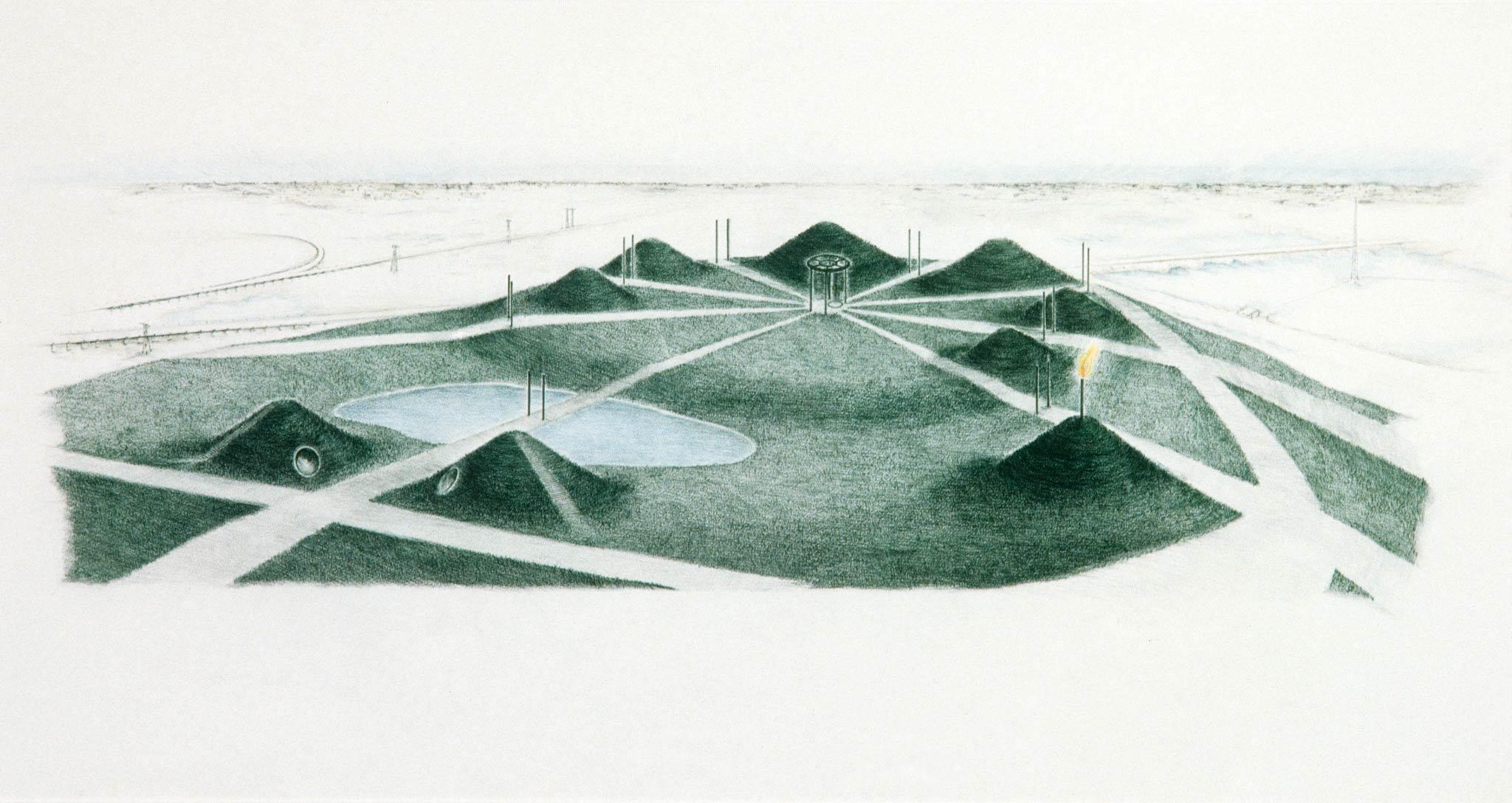

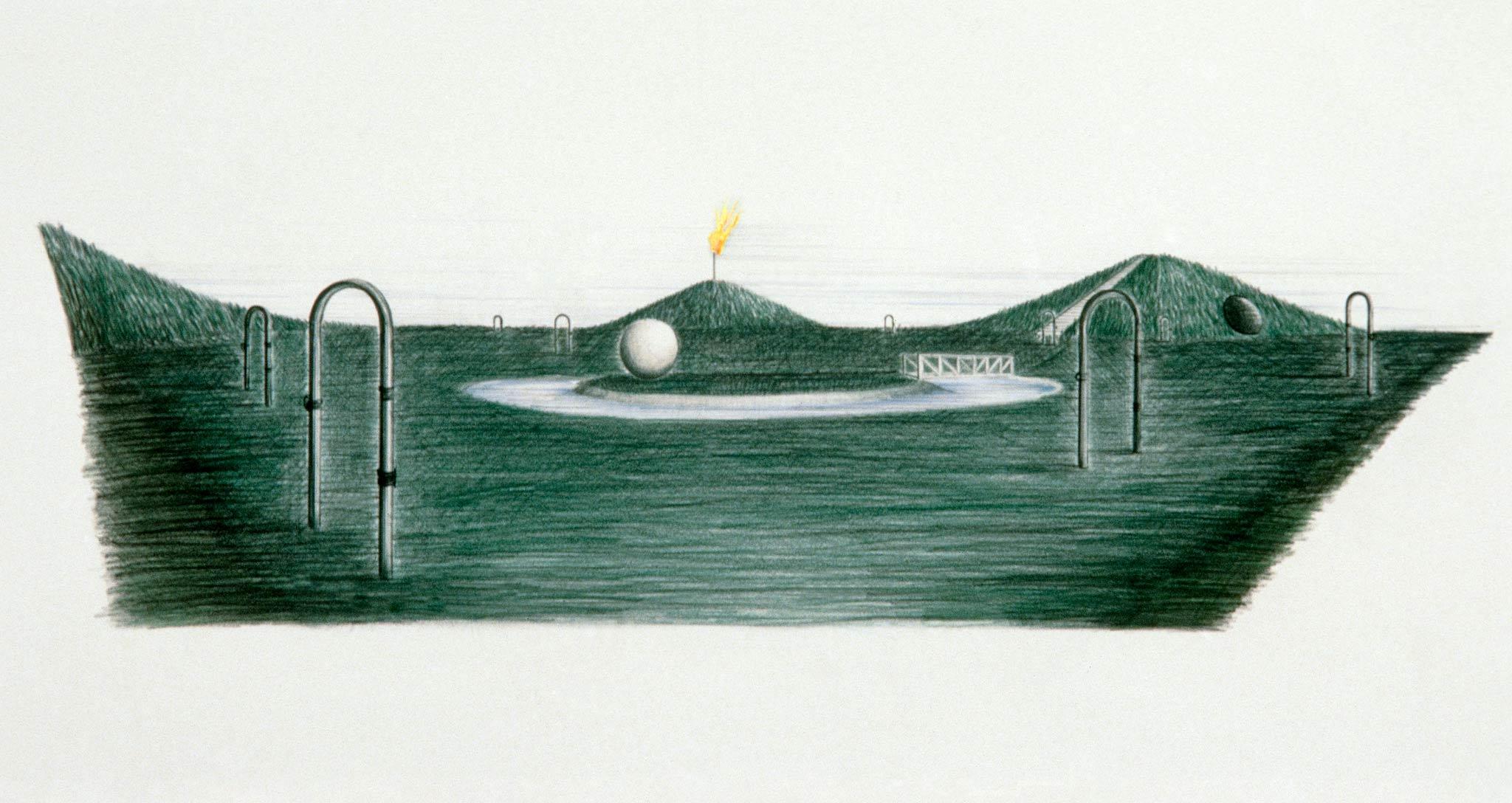

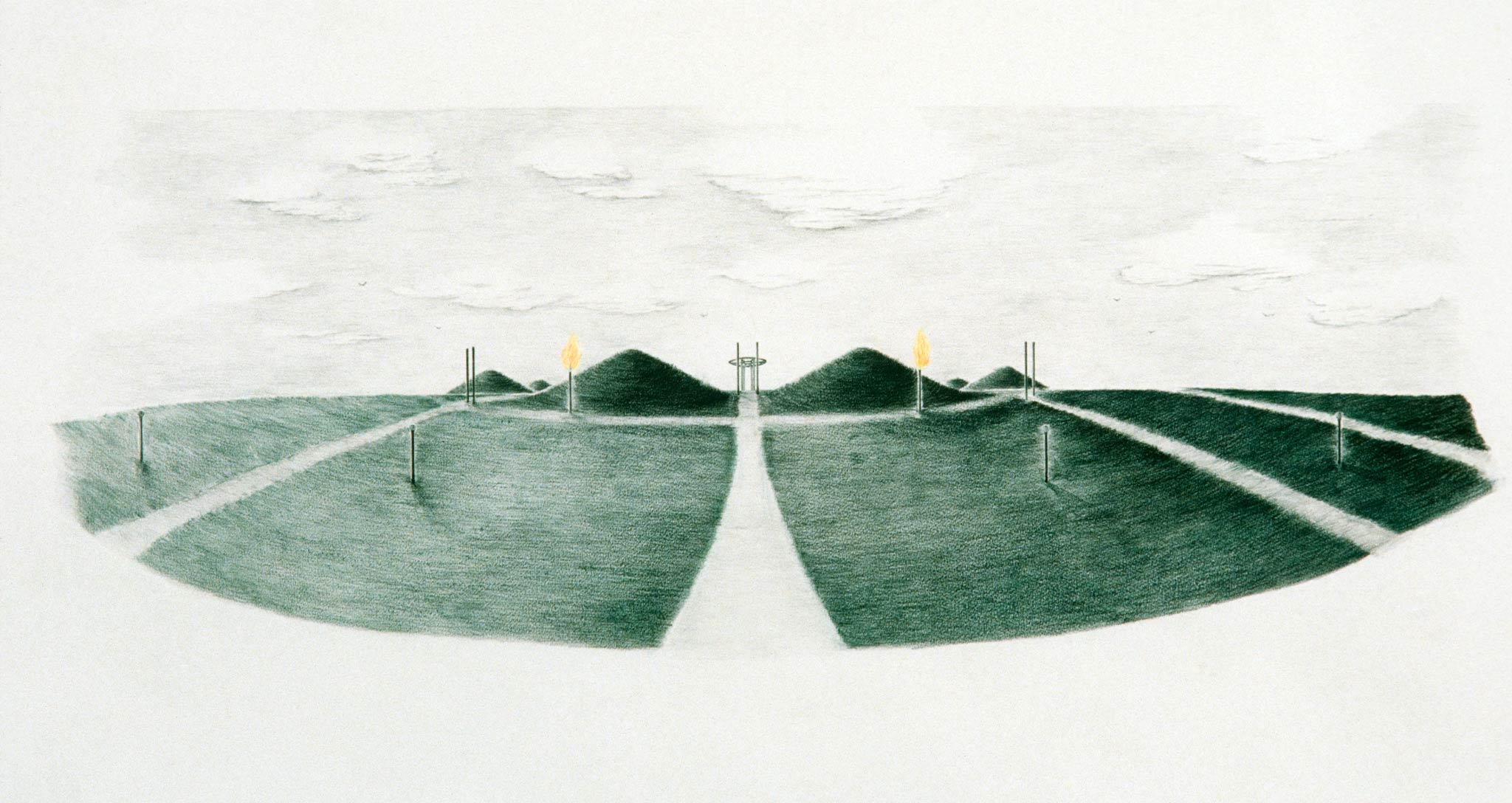

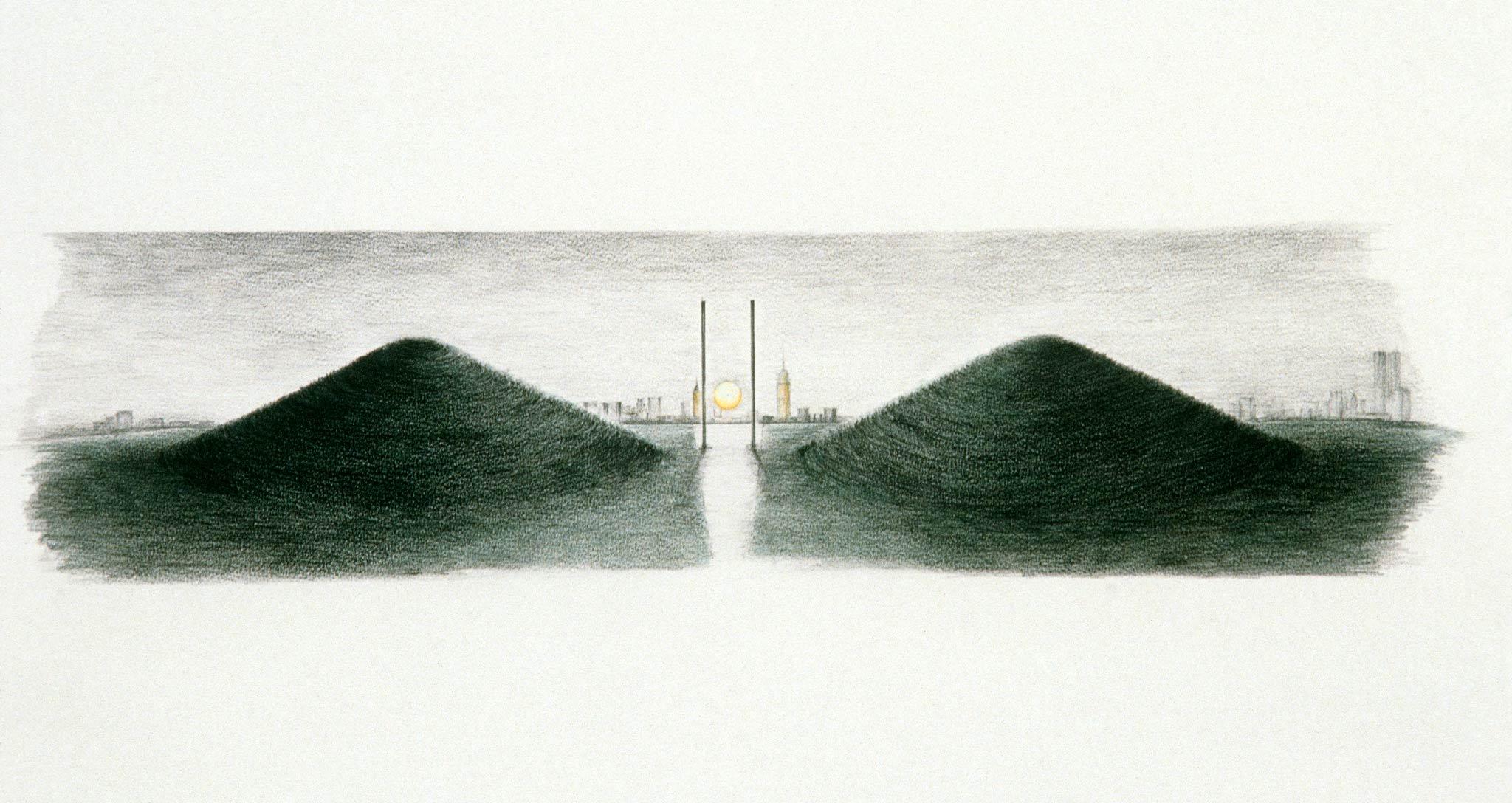

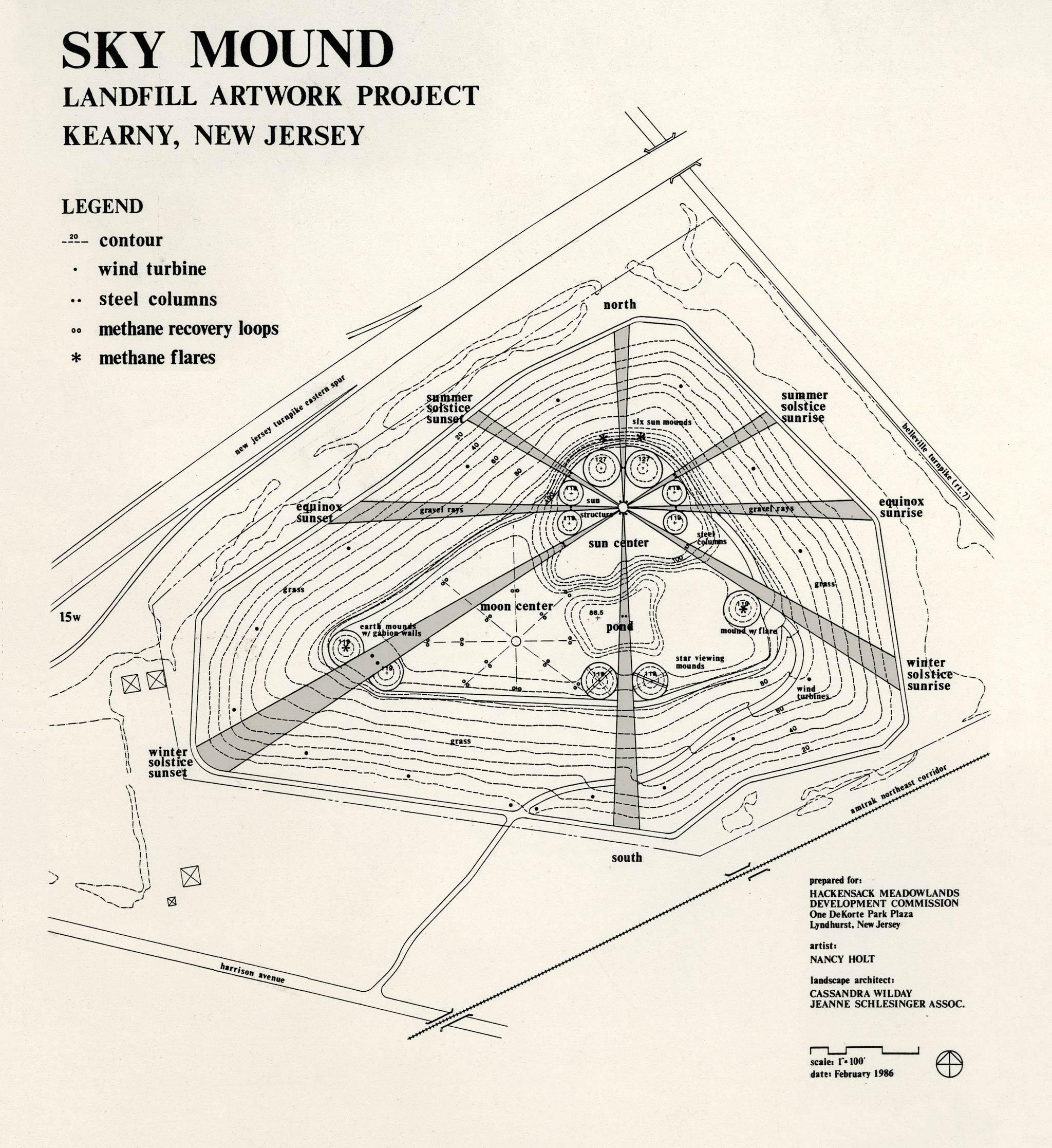

Conceived as a landfill reclamation project in an industrial wasteland dotted with garbage dumps and crossed by highways in the vicinity of Newark Liberty International Airport, Holt’s mound was supposed to emerge as a green landmark and visionary experience for millions of car and airplane passengers, allowing for a suspension from the flux of the present and a reconnection with the cyclical rhythms of solstices and equinoxes.1 A hill of greenery with a pond on top (which was the only feature of the original design that was built), Sky Mound was divided into areas associated with the sun and the moon, reminiscent of a celestial observatory, and was meant as a space to explore in itself, by walking around, or as a site to contemplate from the car by drivers heading elsewhere. Its status as meaningful site of difference was intended to be immediately visible to the naked eye. It would announce to incoming visitors entering the country and the state through the gateway of Newark that the Meadowlands were no longer an environmental wasteland, but rather a place of artistic innovation and ecological responsibility.

When Holt was officially designated by the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission to reclaim the landfill in 1984, she was an internationally recognized public artist who had just finished the reclamation project Dark Star Park (1979-84) in Rosslyn, Virginia, in a blighted urban area. Sky Mound articulated artistic and engineering aspects meant to develop simultaneously, and reconciled a whole series of contradictory concerns. The project posed technical challenges connected to the regulated procedures of landfill closure, but its state-of-the art technology was balanced by a contemplative dimension that invited premodern ways of looking at the world. It dealt with twentieth-century waste, but its aesthetic models lay in the past (Native American mounds in particular). It used waste as material in a design that emphasized celestial observation, thus combining the low and the high, the mundane and the elevated. It covered up waste only to reveal its status as the end result of human production. The project was anchored locally, in the environmentally degraded area of the Meadowlands, but also in larger industrial and symbolic geographies.

The material in the Nancy Holt archives, held at the Archives of American Art, offers invaluable glimpses into Holt’s preparatory process and reveals her high ambitions for Sky Mound. Its history can be traced through a series of archival records (letters, drawings, lists, applications, official documents) that show its various stages, from its enthusiastic beginning in 1983, with a contract signed in 1984, to its disappointing suspension in 1991. She exchanged with many collaborators, including landscape architects, engineers, and astro-archeologists, as she had already done for Sun Tunnels (1973-1976). Holt researched the history of the Meadowlands, its flora and fauna, the latest engineering solutions for landfill closure, and the life cycle of garbage.2 She was very active advertising the project to a large number of interlocutors in New Jersey, the United States and abroad, from businesses to art critics, academic audiences and journalists, and assiduously looked for funding, writing letters and applications, some of which were successful. Sky Mound received recognition and enjoyed massive publicity. On 19 November 1986, it was awarded a Design Honor Award from the New Jersey Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects. Holt followed the construction very closely in its engineering, financial, and organizational details.

One of the most interesting aspects of Sky Mound concerns Holt’s belief in its value and importance. In written presentations, talks, and conversations with journalists, she emphasized its originality and scope, both aesthetic and environmental. Articles quote her remarks on its sheer size (the mound spreads over fifty-seven acres and it was going to be the largest artwork in the north-east of the United States) and its innovative character, since landfills had previously been transformed into recreational areas, ski slopes or golf courses, but never works of art: “We’re breaking new ground here. This is going to set a precedent with an aesthetic way of dealing with landfills.”3 She defines herself as an artist who brought art outside museums, as an author of System Works embedded in everyday life: “I’m breaking down the barriers that separate art from the rest of the world. Art has to be a necessary part of society. It has to meet the needs of a society, not just be a precious object isolated in a museum or gallery.”4 Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, and Robert Morris also embarked upon reclamation projects,5 but Holt chose a new kind of site: a highly visible landfill. Holt assesses Sky Mound as a work with incredible exposure compared to museums, even the most prestigious ones: “the exposure, Holt notes, is ‘better than at the Met.’”6 Holt’s estimation was that the landfill was visible to at least 125 million people annually.

The journalists who wrote about Sky Mound at the end of the 1980s placed it within a real and symbolic geography. It is repeatedly described as “Trashhenge” and “Mount Trashmore,” calling to mind European prehistoric monuments (a comparison that Holt resisted) and famous American monuments. Situating herself in contexts radically different from those of American Transcendentalism, Holt thinks of Sky Mound as belonging to a distinct paradigm from Thoreau’s Walden, one of highway infrastructures and garbage: “You can’t build Walden Pond in the middle of the New Jersey Turnpike. But you can build something using the materials of the place and giving them another significance.”7 Holt comes tangentially close to Thoreau, however, in the search for a feeling of wonder and an attitude of reflection: “It’ll cause wonder. That’s what I’d most like—people wondering. ‘Why does this exist? What is the meaning?’ And when they’re asking these questions of themselves, they’ll stumble upon the answers and have another kind of understanding of the universe.”8 As a resident New Yorker and a native of New Jersey who had experienced the vastness of the American West, Holt embeds Sky Mound in this interconnected geography: the New York skyline is visible from the top of the mound whose open vision of the sky is reminiscent of the West, far from the “canned” insight provided to city-dwellers by science fiction films or planetarium environments.9 This vision was not simply visual in nature, but also involved a reflexive, contemplative, and didactic process. Garbage is the starting point for a quasi-alchemical transformation. Sky Mound sought to place observers in a contradictory position that allowed them to consider the environmental challenges of garbage as a result of their own way of life, but also to experience the sublimity of the sky and to orient themselves to celestial phenomena from the eminence of a landfill.

The Hackensack Commission decided to abandon the project in 1991, invoking lack of sufficient information on the ongoing landfill settlement, which would have affected the design. Holt expressed her disappointment in a handwritten note, noting that she considered this to be the most important project of her career: “I’ve put a great deal of time, energy and commitment into this project. This work is my life’s work—I saw it as my major artistic achievement. (…) Any integrity in my profession is on the line. In the past when I said something was going to happen it always happened.”10

Despite its incompleteness, Sky Mound remains a testimony to Holt’s bold vision of the afterlife of a landfill and the ways in which it could have transformed the landscape and ourselves.

Selected Bibliography

Beardsley, John, “Earthworks Renaissance,” Landscape Architecture Magazine, June 1989, vol. 79, no. 5, 45-49.

Kenan, Naomi, “From garbage to fine art,”, Gold Coast, January 1987, 12-13.

Holt, Nancy papers, Archives of American Art, The Smithsonian Institution.

Holt, Nancy, “Sky Mound. Proposal Draft, 1986,” in Nancy Holt, Sightlines, ed. Alena Williams, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011, 214-217.

Holt, Nancy, “Ecological Aspects of My Work,” 1993. Nancy Holt / Inside Outside, Bildmuseet/Holt-Smithson Foundation, Monacelli, 2022, 197-201.

Rozansky, Michael, “From a trash heap,” The Star-Ledger, October 30, 1986.

Stapinski, Helene, “Artist gets her ‘fill’ of garbage,” The Corporate Reporter. The Office Newspaper, April 9, 1987, vol. 1, no. 14.

Westfall, Stephen, “The Art of Trash,” New Age Journal, March/April 1987, 10-11.

About the Author

Monica Manolescu is Professor of American literature and art at the University of Strasbourg, France, and an honorary member of the Institut Universitaire de France. She is Marc Bloch Associate Chair of Humanities at the University of Strasbourg Institute for Advanced Study for the academic years 2024-2026. Her fields of research are twentieth-century and contemporary American fiction and post-1960 American art. She has published books and articles on Vladimir Nabokov, contemporary American writers and American artists associated with Minimalism, Conceptualism and Land Art. She has been a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, in the Program for Interdisciplinary Studies, an honorary research fellow at the University of Kent and a visiting professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo.

With support from Henry Luce Foundation

This Scholarly Text is supported by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to further our public-facing research into the art and ideas of Nancy Holt.

- 1For a description of the project, see Nancy Holt, “Sky Mound. Proposal Draft, 1986,” in Nancy Holt, Sightlines, 2011, 214-217. See also Holt’s “Ecological Aspects of My Work,” 1993, Nancy Holt / Inside Outside, Bildmuseet/Holt-Smithson Foundation, Monacelli, 2022, 197-201.

- 2An advertisement one finds in a folder at the archives points out the resistance of plastic to degradation.

- 3Holt quoted in Michael Rozansky, “From a trash heap,” The Star-Ledger, October 30, 1986.

- 4“Holt quoted in Helene Stapinski, “Artist gets her ‘fill’ of garbage,” The Corporate Reporter. The Office Newspaper, April 9, 1987, vol. 1, no. 14.

- 5John Beardsley, “Earthworks Renaissance”, Landscape Architecture Magazine, June 1989, vol. 79, no. 5, 45-49.

- 6Holt quoted in Stephen Westfall, “The Art of Trash,” New Age Journal, March/April 1987, 10-11.

- 7Holt quoted in Naomi Kenan, “From garbage to fine art,”, Gold Coast, Jan 1987, 12-13.

- 8Holt quoted in Michael Rozansky, “From a trash heap,” The Star-Ledger, October 30, 1986.

- 9Holt quoted in Naomi Kenan, “From garbage to fine art,”, Gold Coast, Jan 1987, 12-13.

- 10Nancy Holt Archives, Folder B5.10, undated. Underlined in original.

Manolescu, Monica. "Nancy Holt’s Sky Mound: 'The exposure is better than at the Met.'" Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 8 (August 2025). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/nancy-holts-sky-mound-exposure-better-met.