2021 Research Fellow: Paige Hirschey

We are pleased to announce our next 2021 Holt/Smithson Foundation Research Fellowship awardee: Paige Hirschey.

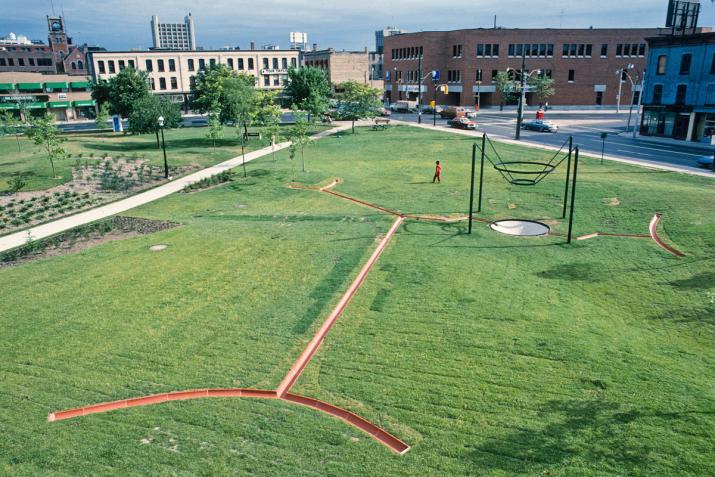

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt, Catch Basin (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

Commissioned by Visual Arts Ontario, Toronto

Steel, terra-cotta, concrete

15 x 90 x 80 ft. (4.5 x 27.4 x 24.4)

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt during the construction of “Catch Basin” (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Nancy Holt during the construction of “Catch Basin” (1982)

St. James Park, Toronto, Canada

© Holt/Smithson Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Catch Basin, an artwork that is also a land drainage system in St. James Park, Toronto, Canada, evolved out of my recent concern with exposing and utilizing functional systems, which are usually hidden beneath the surfaces of our existence. These structural, functional networks—electricity, drainage, heating, plumbing—are basic technologies which support our everyday lives, but are usually only considered when breakdowns occur.

With Catch Basin a branching network of clay channels on the land surface directs rainwater draining off the park slopes to a circular concrete basin with a sunken radial grate, and beneath that, to a round black drain. Catch Basin thus catches, contains, and channels the rain.

About ten feet above the sunken grate two steel rings are suspended from fifteen-foot posts by chains. The rings are the same diameter as the basin rim and the grate, echoing their structure and depth above. Circles of sky are framed through the rings, the entire structure of the work bringing the sky, as well as the water, down to earth.

Catch Basin is built to be functional—its function is visible only when it rains, at a time not generally considered ideal for viewing art. The rain washes down the grassy slopes into the channel pipe, following the natural topography of the land and flowing always toward the lowest point—the center—disappearing finally through the hole in the drain to be absorbed by the gravel and earth below. In the case of a torrential rain, there is an overflow pipe to channel floodwater into the city's underground drainage system.

It is not necessary to actually see the sculpture work when rain is falling; what is essential is that the sculpture has a functional aspect. Without the presence of rainwater one can still imagine the missing element, giving the work a potential—a sense of what might be. The structure of Catch Basin tracks its own function.

Catch Basin can evoke ancient drainage systems, some of the oldest of which have been in use since 5,000 B.C. in Crete. Egypt and Babylon drained wetlands, and Cato in 200 B.C. discussed farm irrigation in Roman land. Drainage technology in North America reached its apex in the late nineteenth century and has remained relatively unchanged since. John Johnston is credited with using tile drainage first in the United States, importing horseshoe-shaped tile from Scotland to his Geneva, New York, farm in 1835. His neighbors scoffed, but in 1848 after his system was successful, an English machine for making tile was brought to America. Since then, on this continent, tile drainage has been responsible for the blooming of deserts and the increase of crops in many places.

Holt, Nancy. “Catch Basin.” Written in 1982, published in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, edited by Alena J. Williams, University of California Press, 2011, pg 114.