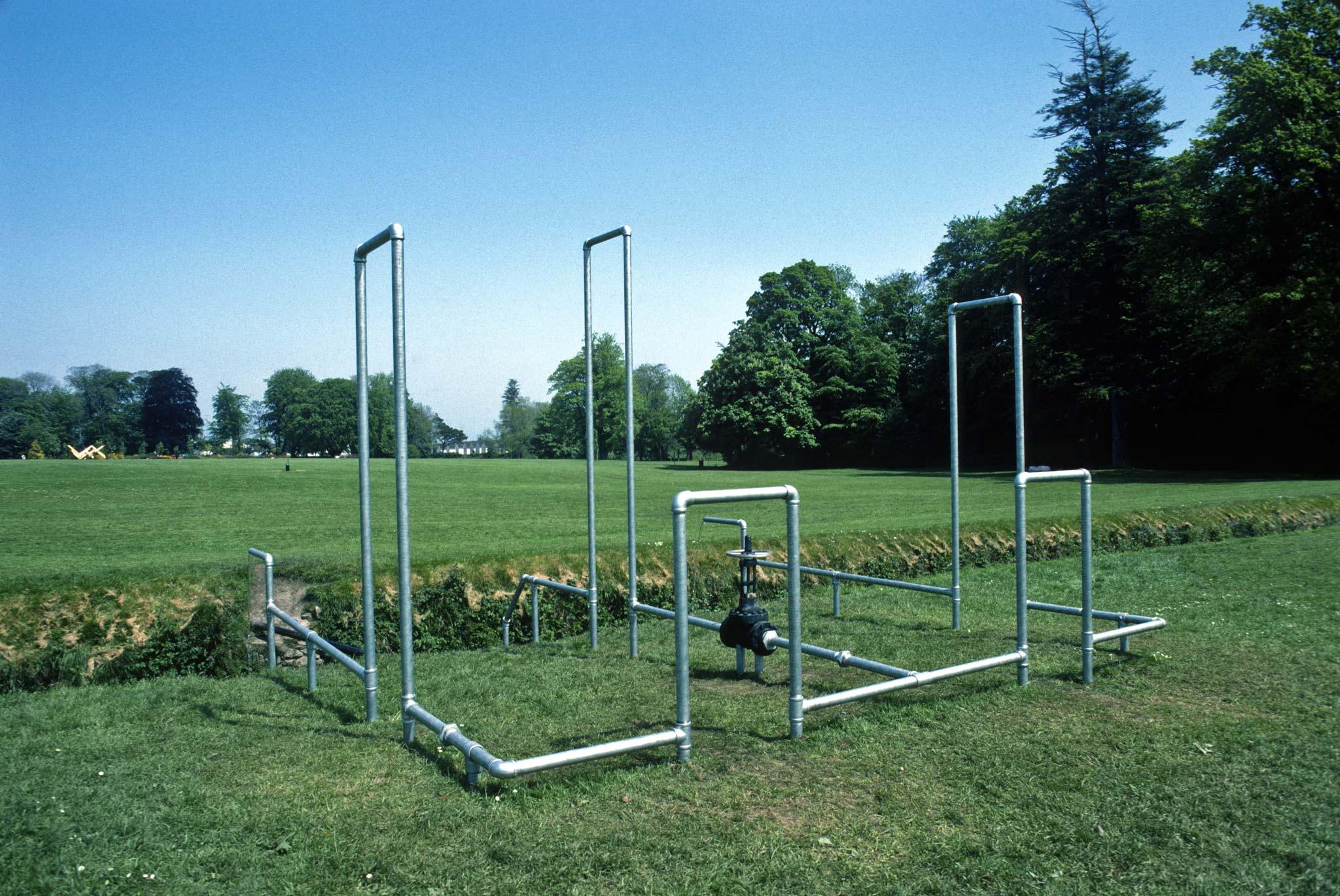

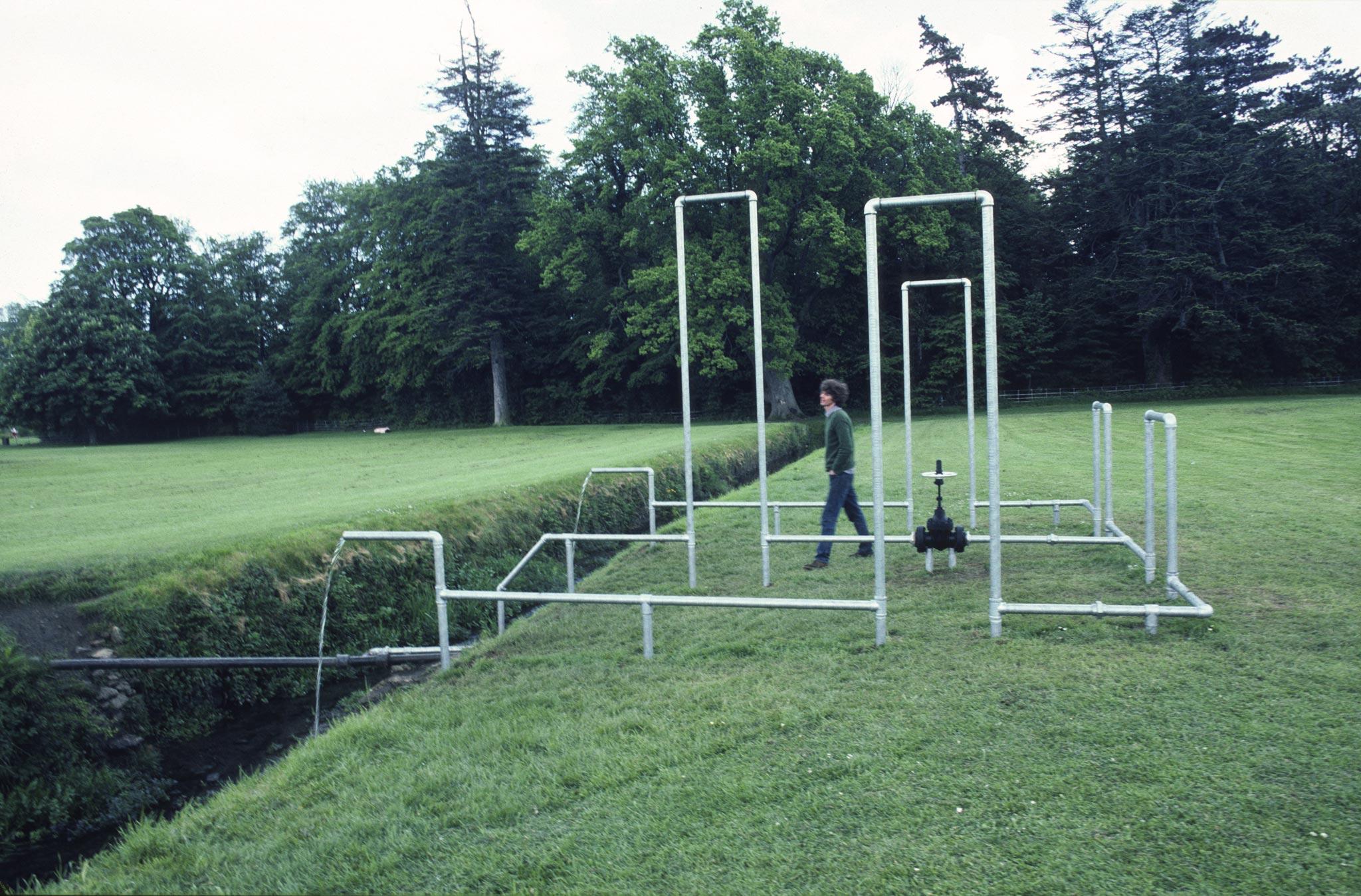

Nancy Holt, "Sole Source," 1983

Nancy Holt’s Sole Source was commissioned by the Independent Artists Group of Dublin as part of the twenty third Independent Artists Exhibition in 1983, which took place across two venues in Dublin: the Douglas Hyde Gallery and Marlay Park in Rathfarnham, at the foothills of the Dublin mountains, around six miles from the city center.1 Holt was one of two international artists invited to participate—alongside British conceptual artist Ian Breakwell. Jenny Haughton, then Administrator of the Independent Artists Group, commissioned Holt to make a work for the Marlay Park exhibition. In an initial letter, she wrote “The park is open plan, whose distant horizons are tall trees. It has no rigid plan, and one can walk along grassy swards for a few miles.”2 Spanning over 300 acres, the suburban park is home to woodlands and large ponds, supplied by the Little Dargle river which runs through it. It is also home to Marlay House, courtyard, and walled gardens, built in 1794 and donated to Dublin County Council in 1972.

Haughton invited Holt to participate in the Independent Artists Exhibition after seeing her Electrical System at John Weber Gallery, New York, in 1982, an installation consisting of numerous lightbulbs connected by metal conduit which illuminated the gallery, creating arches of light for viewers to walk among. Site-responsive, this iterative work was named Electrical System (for Thomas Edison) in this presentation, one of two realized in her own lifetime. Electrical System (for Thomas Edison) was one of Holt’s earliest System Works—a body of artworks largely overlooked in her lifetime, but especially prescient in their exploration of natural resources and the basic industrial systems which we are reliant upon, but often barely conscious of. She wrote:

Using basic technological systems, such as plumbing, electrical, drainage, heating and ventilation systems, my System Works exposed sections of vast, ordinary hidden networks. Over the years these technological systems have become necessary for our everyday existence, yet they are usually hidden behind walls or beneath the earth and forgotten. We have trouble owning up to our almost total dependence on them. Yet with greater awareness of these systems, the channeling of the energy and elements of the earth can be done intelligently with the long-term benefit of the planet in mind. In doing so, we become nature’s agents, rather than aggressors against nature.3

While a number of Holt’s System Works explore heating, ventilation, and electricity, Sole Source is part of a series considering water, drainage, and irrigation. Holt first explored this in her photographic series Miami Puddles (1969), in which she captured with her camera pools of water gathered as a result of heavy rainfall in the dips of roads, sidewalks, street corners, and parking lots across the city. In 1981, she created a proposal for a System Work titled Drainage System at Wave Hill in the Bronx, New York, a configuration of open terracotta channels which would collect rainwater as it flowed through pipes into the adjacent Hudson River. In 1982, she completed Catch Basin in St James Park, Toronto, an outdoor sculpture which used inverted terracotta channel pipes to catch, channel, and contain rainwater. In 1983, Holt submitted a proposal for Roundabout (which was unrealized), to the Art in City Life Commission for the Kennedy Transit Mall in Providence, Rhode Island. This sculpture would have comprised of four tiered pipes joined together by a circular pipe which allowed water to fall into a pool below; with circular valves on each of the four legs that would enable visitors to control the flow. In 1984, she completed Waterwork at Gallaudet College in Washington DC (dismantled in 1995), “a participatory fountain of sorts”4 in which water from a reservoir was channeled through Holt’s system of pipes and back down into the existing drainage infrastructure, before returning to the river. The water could be turned on and off by visitors using two taps at certain times of the day, the participatory element regulated by a timer.

Holt was allocated a modest budget of £10005 for the Marlay Park commission and arrived in Dublin without a preconceived idea of what she would make.6 She stayed for around two weeks to research and construct the work, and delivered a lecture followed by a film screening on May 28, 1983, as part of the opening program of events. Holt worked collaboratively to realize her public artworks—with plumbers, mechanics, construction workers and those with specialist local knowledge—and was closely involved in the construction process of Sole Source.7 In an interview with Micky Donnelly in Circa Magazine about the commission in the year of its completion, she commented, “I arrived here [in Marlay Park] and it seemed like everything fell into place; there is a very good spirit, and there was a harmony to this whole thing. Also, there was an incredible amount of help from Eoin O’Toole… I couldn’t have done it without him.”8 O’Toole was a member of the Independent Artists Group and project manager for the Sole Source commission. He and Holt shared an interest in archaeology and prehistory, and he took her to visit sites such as Newgrange, a Neolithic passage tomb located in the Boyne Valley, whose inner passage aligns with the Winter Solstice sunrise, as well as cairns, standing stones, and ancient structures sited on ley lines.

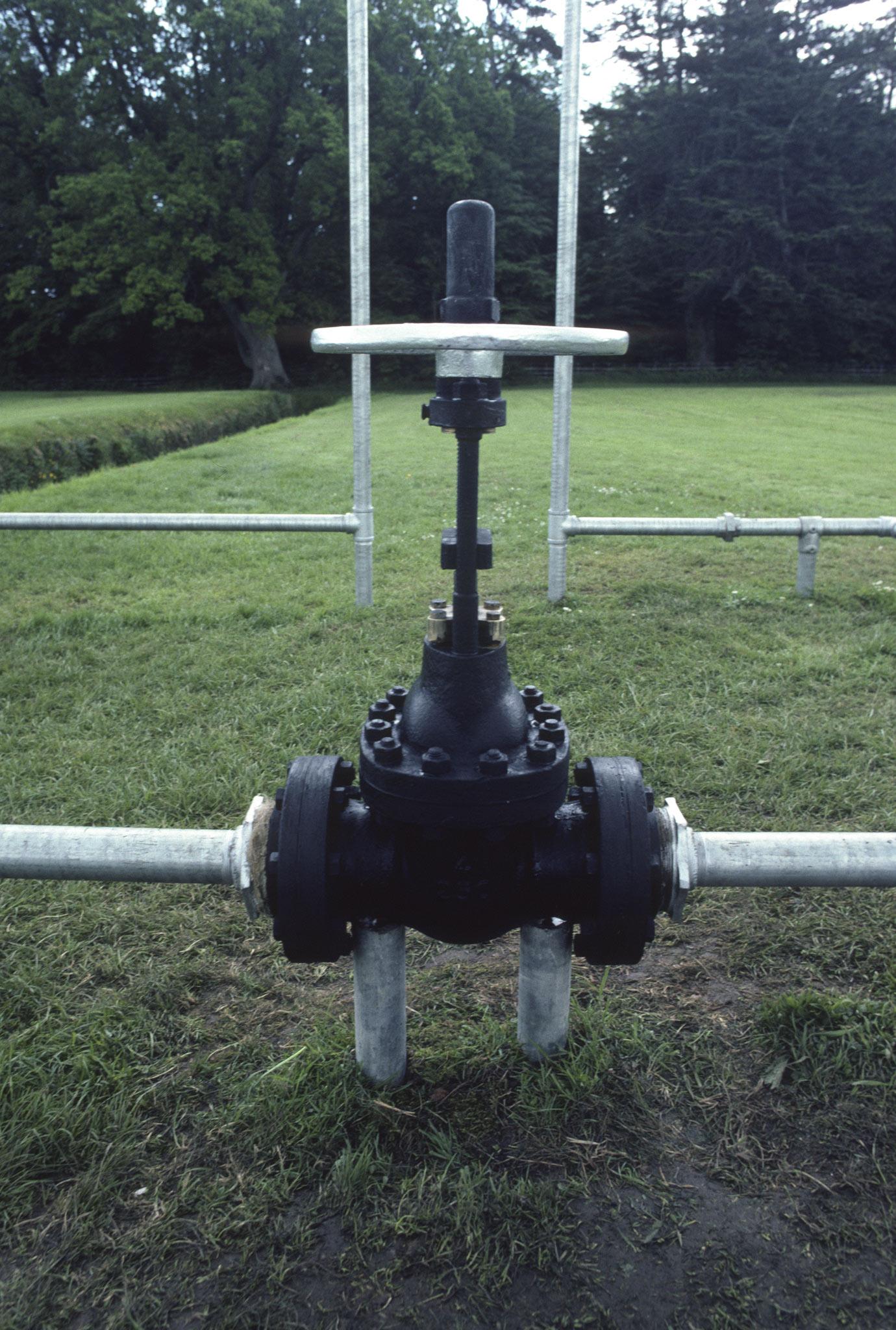

After walking the grounds of Marlay Park, Holt focused on the “ha-ha”9 —a sunken ditch common to eighteenth-century landscaped gardens—in front of the southern elevation of the house and a cast-iron four-inch diameter water pipe which carried water from an elevated reservoir and supplied the house and gardens. After gaining permission to tap the pipe, she made pencil and charcoal drawings and a maquette of a tubular structure to visualize how she might plumb into the pre-existing system. Holt and O’Toole visited two architectural salvage sites to look at scrap plumbing material and selected several galvanized steel pipes, including a 30-inch-long pipe with a 4-inch diameter and a circular handle in the shape of a Celtic cross which could be rotated to control the flow of the water in the finished sculpture.10 The Celtic cross is also known as the sun cross: the sun was a consistent reference for Holt, as can be seen in the 1972 photographic series California Sun Signs and the earthwork Sun Tunnels (1973-76).

O’Toole was instructed to cut the pipes to the lengths required according to Holt’s calculations, and it took three to four days to dig the foundations, plumb on to the main pipe, and assemble the structure. Holt titled the work Sole Source—the water originated from a single source, split in two as it was channeled through the new plumbing system before flowing, via two end pipes, into the earthen ditch and eventually back into the river. For Holt, it was essential that the sculpture operated on a human scale and had a functional element, even if the appendages were not necessary or useful—she commented:

Art needs to be a more necessary part of the world, of society. And, in those works like Sole Source that actually have function in them as part of the work, within the art itself that statement is made. The system is emphasized; the function becomes the content of the work… With this piece in the park, here we have this elaborate system of pipes and we’re just getting these little streams of water out at the end. I just love the uselessness of that. So it functions, but it’s not grand, it just is. It’s laughable, in a sense all of this for that! So really I’m just trying to expose these systems.11

The participatory potential of the sculpture was both playful and intended to bring an awareness of the elements flowing through it. We turn on the water indiscriminately multiple times each day without thinking about its source, and while the practice of channeling water dates back the aqueducts of Ancient Greece and Rome, running water and indoor plumbing became accessible only at the beginning of the twentieth century. In making visible infrastructure which usually remains hidden, Holt hoped to make viewers aware of these underground networks and our dependence upon this technology, advocating for a greater consciousness of natural resources and consideration of human impact upon the planet.

Sole Source was one of a handful of works Holt realized in Europe. She spoke of its dissemination through documentation in a letter to Haughton dated 19 June 1983, writing, “here in NY where there might be more of a context for it, the response to the photographs has been encouraging.”12 The preparatory maquette was later exhibited at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut in 1985. In the 1983 exhibition catalog, Catherine Carman, then Chair of the Independent Artist Group, discusses an ambition for Marlay Park to become the first sculpture park in Ireland, writing that Holt’s sculpture “will be an important addition to the collection.”13 Holt also anticipated that the work would remain in situ—in her letter to Haughton, she describes her time in Ireland as “unforgettable” and writes “I hope Sole Source can remain indefinitely so visitors will be able to see it. There is always a time lag between my finishing a work and getting it out into the world.”14 She also hoped that critic and writer Lucy Lippard, who had recently published Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory, might be able to visit the work on a forthcoming trip to the UK.

While it was often Holt’s wish that her public commissions would be semi-permanent, the maintenance that the works required was often prohibitive. Although Marlay Park did not become a sculpture park, Sole Source was in place for several years following the 1983 exhibition, thanks to regular, voluntary maintenance by O’Toole. The following year Holt entrusted O’Toole to assist with the construction of her System Work Hot Water Heat at John Weber Gallery, New York in 1984, which functioned as the heating system for the gallery. The tight schedule and lean budget meant that Sole Source was amongst the more modest of Holt’s System Works in scale, yet by exposing and extending the pipework, she encouraged visitors to think about the vast underground infrastructure that we depend upon, the source and supply of water, and the fact that the resources we use are limited: even more so forty years after the work was conceived.

Selected Bibliography

Holt, Nancy. Oral history interview by Joyce Pomeroy Schwartz, August 3, 1993, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Holt, Nancy. “Ecological Aspects of my Work” (1993) in Le Feuvre, Lisa and Pierre, Katarina eds. Nancy Holt: Inside Outside (New York: Monacelli Press, November 2022).

Marter, Joan. “Systems: A conversation with Nancy Holt,” Sculpture Magazine vol. 32, no. 8 (October 2013).

McNulty, Dennis (ed.) Everything is somewhere else (Dublin: Paper Visual Art, June 2020).

Williams, Alena J. (ed.) Nancy Holt: Sightlines (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

About the Author

Grace Storey works at Hollybush Gardens, London. Previously she was Assistant Curator at Whitechapel Gallery, London, and worked on projects including Paulina Olowska: The Travel Bureau (2022); Simone Fattal: Finding a Way, Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, and Sol Calero: Desde el Salón (all 2021). She has also held positions as Assistant Curator at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, and Studio Manager in New York for Camille Henrot, realizing Henrot’s exhibition Days Are Dogs at Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2017). She holds an MA in Curating Contemporary Art from the Royal College of Art, London, and a BA (Hons) History of Art from the University of Warwick.

- 1The Douglas Hyde Gallery exhibition ran from 28 May–18 June 1983, and the Marlay Park exhibition from 29 May–30 September 1983.

- 2Letter from Jenny Haughton to Nancy Holt, 27 February 1983; held in the archive of Jenny Haughton

- 3Nancy Holt, “Ecological Aspects of my Work” (1993), in Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre eds. Nancy Holt: Inside Outside, (New York: Monacelli Press, November 2022), 197.

- 4Joan Marter, “Systems: A Conversation with Nancy Holt,” Sculpture Magazine, October 2013. https://sculpturemagazine.art/systems-a-conversation-with-nancy-holt/; last accessed 12/17/23

- 5Irish £.

- 6Letter from Jenny Haughton to Nancy Holt, 27 February 1983. The £1000 fee also included Holt’s travel and accommodation for the trip; held in the archive of Jenny Haughton.

- 7Nancy Holt, oral history interview by Scott Gutterman, July 6, 1992, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Holt discusses her approach to collaborating with skilled workers, and the importance of these close working relationships. “I work with a really good person, somebody who cares. So I depend on—I don’t know how to do plumbing, but I depend on my friends… There are quite a few artists that do site specific work that allow a lot to happen when they’re not there. I can’t imagine that. I’m there every day and I get very close to the people that I’m working with. In fact, I’m very particular about who I work with. I interview a lot of people. If I have to get some concrete work done, I send out plans to maybe five or six different places, and talk to different people, and usually you can find one who will see the work as a challenge, and who is happy to be involved with something like this. Plumbers and electricians are artists, and actually, my first ventilation piece was with an artist. But when I do the big outdoor pieces, I’m working with professional masons… they throw themselves into the work because it’s a monument to their skill.”

- 8Micky Donnelly and Nancy Holt, “Nancy Holt interviewed by Micky Donnelly”, Circa Art Magazine, Issue 11 (July–August 1983). https://circaartmagazine.net/circa-issue-11-nancy-holt-interview-by-micky-donnelly/; last accessed 12/17/23

- 9Ha-has are sunken ditches which became popular in eighteenth-century landscape garden design to replace walls and fences and open up views of the surrounding landscape, while also providing boundaries for grazing livestock.

- 10A sun cross, or wheel cross is a solar symbol consisting of an equilateral cross inside a circle. The design is frequently found in prehistoric symbolism, particularly during the Neolithic to Bronze Age periods. Micky Donnelly and Nancy Holt, “Nancy Holt interviewed by Micky Donnelly”, Circa Art Magazine, Issue 11 (July–August 1983). Holt discusses her interest in the usually overlooked detailing found on manhole covers: “I’m fascinated by all these manhole covers and water-main covers. There are some beautiful ones outside here with flowers on them, like mandalas. We live in a world of steel mandalas on the streets, and nobody wants to really take a hard look at them.”

- 11Micky Donnelly and Nancy Holt, “Nancy Holt interviewed by Micky Donnelly,” Circa Art Magazine, Issue 11 (July–August 1983).

- 12Letter from Nancy Holt to Jenny Haughton, June 19, 1983 in Dennis McNulty ed. Everything is somewhere else (Dublin: Paper Visual Art, June 2020)

- 13Catherine Carman ed. 1983 Independent Artists Exhibition catalog. Catherine Carman writes “In 1982, Marlay Park was the venue for the first open-air sculpture show of the Independent Artists. The success of this event led to the purchase of four works through the joint purchase scheme of the Arts Council and Dublin County Council.”

- 14Nancy Holt, oral history interview by Joyce Pomeroy Schwartz, August 3, 1993, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Holt says “In the seventies, most people were doing these temporary structures that would come down at the end of the show… from the very beginning, anything outdoors I would always make it so strong that it was going to be there for centuries, and they generally ended up remaining. Even if it was a temporary art show.”

Storey, Grace. "Nancy Holt, Sole Source, 1983" Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 7 (October 2024). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/nancy-holt-sole-source-1983.