Florida, Man: Robert Smithson’s Hypothetical Continent in Shells: Lemuria

Before sunrise on an already soupy Monday in mid-August 2023, scores of white contractor pickups from mainland Florida clogged the causeway bridge onto Sanibel, a narrow, crescent barrier island curving twelve miles along the Sunshine State’s southwestern Gulf Coast. Ten months earlier, Hurricane Ian had thrashed the island, leveling homes and businesses, disemboweling infrastructure, and clobbering complex, verdant ecosystems filled with alligators, marsh rabbits, black racer snakes, river otters, iguanas, gopher tortoises, and legions of bird species.

Six thousand years ago, as the Everglades were forming, Sanibel and Captiva, its sibling island to the north, emerged as one topography. The Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 cleaved them in two. Every forty-odd years, hurricanes smite Sanibel. There was Donna in 1960 and Charley in 2004. Ian was early. Then, each time, locked in a preternatural loop of construction and demolition, Sanibel’s residents, alongside disaster relief workers, bricklayers and framers, and wildlife refuge staff, wade through the wreckage and rebuild.

Part spiraling Biblical suburbia, part prehistorically vegetal portal, Sanibel was a honeypot for Robert Smithson.

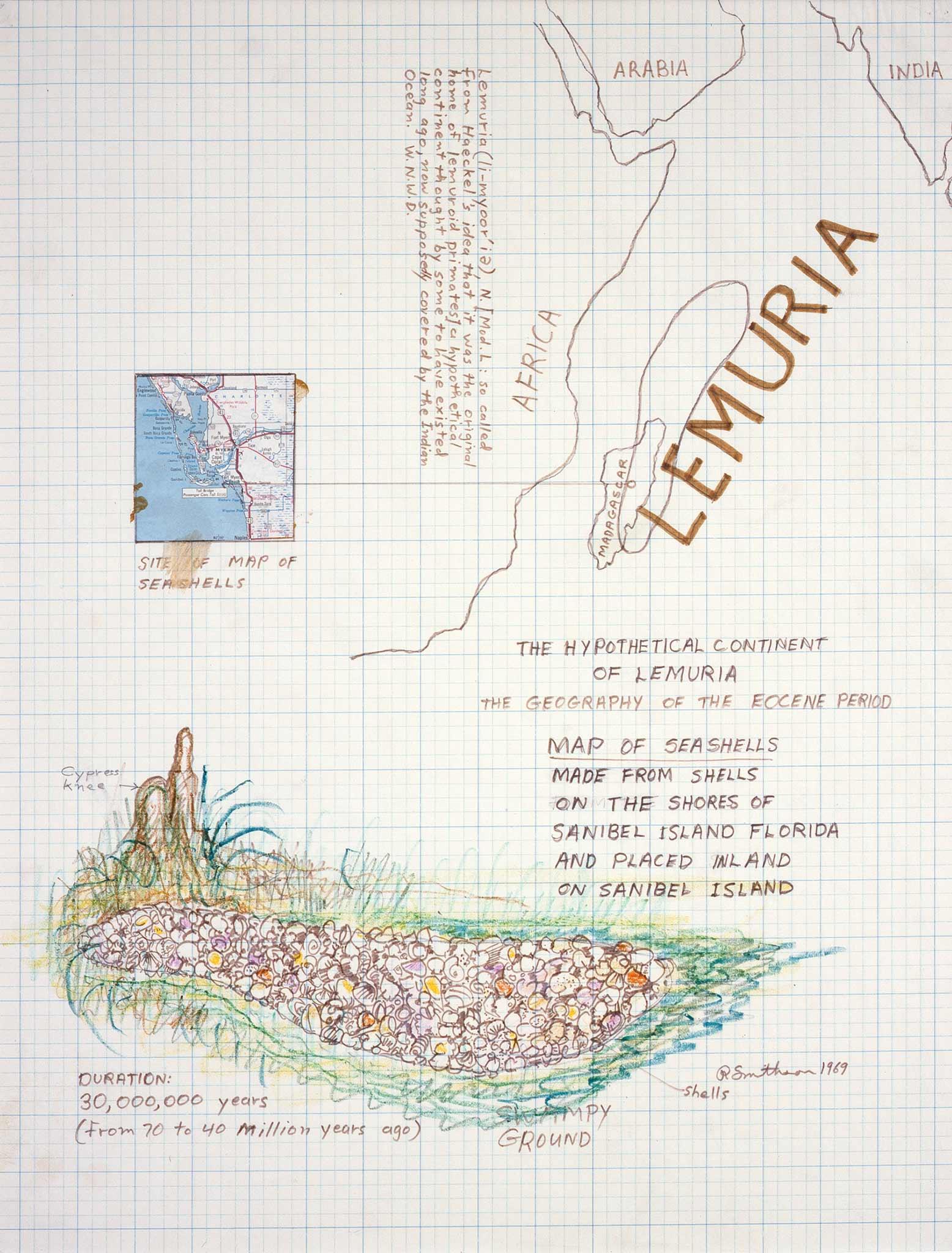

As a child, Smithson’s family took trips from New Jersey’s industrial-scarred pine and oak corridors down to Florida—including a visit to Sanibel1 —where extraordinary humidity and non-Euclidian greenery produce a shimmering, tropical-floral sublime. Later, in young adulthood, with designs on becoming a naturalist, Smithson frequented Ross Allen’s quirky Reptile Institute in Silver Springs2 . In April 1969, now in his thirties and en route to Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, the artist returned to Sanibel and Captiva. He buried an inverted tree on Captiva (Upside Down Tree II) and collected seashells along the white sands of Sanibel’s Bowman Beach for two works. Mirror with Crushed Shells (Sanibel Island) was a Nonsite, or an “indoor earthwork,” transporting materials from the natural world into the gallery space3 , later shown as a corner mirror work.4 Hypothetical Continent in Shells: Lemuria was an in-situ gastropod and bivalve “earth-map” plotting the titular Lemuria, a fictional sunken landmass in the tradition of Atlantis. Today, Lemuria only exists in four 126 format chromogenic slides, though Smithson’s ephemeral gesture mediated the charged landscape to such a degree that the work reverberates, phenomenologically, into hypothetical pasts and futures.

Six hours up the Gulf Coast from Sanibel sits St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, an elaborate coastal ecosystem of river estuaries, tidal channels, and saltwater marshes, surrounded by enveloping, fractal forests of sabal palm, red cedar, yucca, and live oak draped with Spanish moss. St. Marks served as the inspiration for Area X, an uncanny ecological exclusion zone central to author Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy (Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance, all 2014). Area X reclaims abandoned buildings, decomposing them at impossible rates. A “topographical anomaly” appears simultaneously as an aerial tower and subterranean tunnel. The landscape itself, like an organic alien mirror, mysteriously gestates an enantiomorph—a gothic chiral double—of several researchers who breach its expanding border. Others go mad and slaughter one another or die by suicide. Of those doubled, the terrain’s eerie flora and fauna subsume their originals. Their copies escape Area X only to rapidly succumb to cancer, negating both bodies.

Smithson, a voracious consumer of critical science fiction like JG Ballard and Eric Temple Bell, might have found a kindred spirit in Area X, whose entropic propensity for swiftly reclaiming humans and their built environments recalls the artist’s Partially Buried Woodshed (1970), which begged for ferality; his Enantiomorphic Chambers (1965), a destabilizing steel and mirror sculpture that doubled, then canceled, a viewer’s reflection; or Catholic-themed drawings from 1962 depicting humans grotesquely merging with trees, a reference to Dante’s nightmarish Wood of Suicides. Coincidentally, in 1961, Smithson generated drawings collectively titled The Days of Atrophy: A Preparation for Annihilation.

In mid-September 2023 at St. Marks, de-domestication encroached. Everywhere along the Cathedral of Palms, a popular segment of the Florida Trail snaking through a densely canopied floodplain hammock, were massive, canonical piles of black dung, trampled vegetation, and gouged soil, evidence of invasive feral hog teams who have overtaken parts of the refuge. Descended from sixteenth-century colonial farm pigs, the thousands of tusked, hundred-fifty-pound boars charging through Florida’s forests vibrate like an auger for Area X.

Where the sentient Area X speculates near, non-anthropocentric futures, the sunken continent of Lemuria projects human significance into the deep past. Lemuria originated in 1864 as a good-faith hypothesis, a Permian and Jurassic land-bridge that might explain fossil distributions indicating identical primates, broadly labeled “lemurs,” across the Indian subcontinent and Madagascar that did not appear on mainland Africa or in the Middle East.5 The land-bridge theory soon swelled into a continental one. Then, a more existentially seductive hypothesis emerged: before a geologic cataclysm drowned Lemuria in the Indian Ocean, it had birthed humankind.6 By the 1880s, Lemuria had leached into extra-scientific fields. Political philosopher Friedrich Engels, geologist William Thomas Blanford, and, later, science fiction spearhead HG Wells all referenced Lemuria.7

Occultist and theosophy founder Helena Blavatsky’s pseudo-scientific treatise The Secret Doctrine (1888) synthesized Atlantis and Lemuria into her “Seven Root Races” emanationist cosmology.8 Ostensibly detailing millennia of lost races on sunken continents, The Secret Doctrine’s second volume, “Anthropogenesis,” repeatedly links racial traits with spiritual and intellectual capacity9 and implies that certain indigenous peoples evolved through lineages of bestiality. Theosophy nonetheless became popular in philosophical, spiritual, and cultural networks. Abstractionists including Mondrian, af Klint, and Kandinsky studied theosophy.10 Earthy illustrator Fidus, whose fantastical nudes bewitched Germany’s early twentieth century back-to-nature, nativist youth movement, was a theosophist.11 Ironically, after joining the Nazi Party in 1932, Fidus was deemed degenerate, sinking into obscurity until offspring of German immigrants in 1960s California—commune-keen, New Age-curious, and tripping on LSD—appropriated his radiating aesthetic into concert posters.12

Despite a growing fixation on earth, fossils, and crystals throughout the 1960s, Smithson was no occultist (nor a hippie). By 1969, Smithson would have absorbed that recent widespread acceptance of continental drift had, scientifically at least, put a nail in the coffin of the hypothetical continent of Lemuria.13 This gives Smithson’s Lemuria, which was not a one-to-one material dislocation like his Nonsites, but a fleeting topographical anomaly, the deadpan quality of an entropic one-liner: these shells represent nothing. Smithson riffed on lost continents throughout 1969, gathering shattered glass into an Atlantis silhouette at the Jersey shore; arranging stones into an ersatz Cathaysia in a riverbed near Alfred, New York; constructing a limestone geo-portrait of Gondwanaland near the ancient Maya city of Uxmal; and drawing multiple “hypothetical continent” maps on paper.

Deluge narratives abound in global religious mythologies, from Noah to Ziusudra to Manu, but the sunken worlds trope has proved particularly fertile for science fiction and fantasy writers like Ballard, Jules Verne, Edith Nesbit, and Neal Stephenson, among countless others. In the early 20th century, American author and weird fiction figurehead HP Lovecraft incorporated Atlantis and Mu—the latter a nonexistent Pacific continental collage of Atlantis and Lemuria14 —into his Cthulhu mythos and other stories. “Weird fiction” is a mode within fantasy and horror genres exploring interdimensional, unspeakable, and ancient terrors that upend humankind’s ordering of the world. Lovecraft himself stewed in terror of the other and made little effort on the page to mask his racist views and perpetual anxieties about immigrants and miscegenation.15 Coincidentally, Lovecraft’s warped perspectives on race rhyme with those extolled by Blavatsky throughout The Secret Doctrine, and while no evidence suggests that Lovecraft subscribed to theosophy, it interested him enough to reference it overtly in “The Call of Cthulhu.”

Beyond the niche worlds of occultism and weird fiction, theosophy’s fantastical, spiritual-libertarian tenets have proved plasticine and oozed—Lemuria-like—into white American culture. Perhaps this betrays a subconscious colonial anxiety. Could sunken continents and lost races satisfy a desire for white indigeneity? Or, through fantasy, permit a renegotiation, rather than a confrontation, with centuries of genocide?16 Theosophical intonations undergird the techno-utopianism of Silicon Valley (and its seamless integration into Burning Man), the wellness influencer sphere, and the post-Covid-19 emergence of a granola-reactionary singularity between yoga enthusiasts, do-your-own-researchers, anti-vaxxers, New Age Christian millenarians, ancient astronaut theorists, and crystal-worshiping circuits from Sedona to Crestone to Mount Shasta (inside of which Lemurians are rumored to live in a city called Telos17 ). These peculiar allies share two tendencies. First, they seem selfish—spiritually, financially, environmentally, and bodily—and thus disinterested in weighing what writer Elvia Wilk calls their ecosystemic bodies,18 which link them inextricably with both proximate and distant but very much real landscapes facing unprecedented threats from anthropogenic climate change. Second, like anyone, they want to be told an entertaining story. The Southern Reach Trilogy’s exciting arc will surely satisfy the latter, and its queered ecologies—its indelible affirmation that plant nature is queer nature19 —might even provide a salve for the former, as would “new weird” books by NK Jemisin, Ned Beauman, KJ Bishop, or Cassandra Khaw, who conceptualize intricate and radical worlds without Lovecraftian othering.

Here in Florida, in 2023, Smithson’s Lemuria, like Area X, inches closer to science-reality. By the end of this century, it is projected that one in eight homes on this politically hysterical peninsula will be underwater.20 In July, ocean surface temperatures in the Florida Keys reached 90 Fahrenheit, and coral reef systems, which support immeasurable life and act as coastal superstorm barriers, are facing extinction.21 A perpetual punchline in itself, Florida is, however, as one scientist put it mirthlessly, but “one patch in a terrible quilt right now.”22 Area X did not recognize human-created borders, and future storms, feral hogs, ravenous ticks, or coastal flooding will not differentiate between red and blue states.

In the early hours of August 30, 2023 Hurricane Idalia clawed through the Gulf of Mexico. This time, Sanibel was spared. And so, the rebuilders can stick to rebuilding what they were already rebuilding. What a relief; the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum, the only accredited museum in the US devoted solely to shells and mollusks, was still under repair, post-Ian. After Smithson left Sanibel in 1969, the artist stumbled across the Hotel Palenque in the Yucatan, a local lodge that was collapsing while being actively rebuilt. He photographed it obsessively, and three years later presented a slide lecture to architecture students in Utah. “It's not often,” Smithson mused, “that you see buildings being both ripped down and built up at the same time.”23 But it probably will be.

Selected Bibliography

Abrahams, Brad, dir. Telos or Bust. Austin, TX: Extrasensory Pictures, Inc, 2022, short.

De Camp, L. Sprague. Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. New York: Dover Publications, 1970.

Flam, Jack, ed. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

VanderMeer, Jeff. Annihilation. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2014.

Wilk, Elvia. Death By Landscape. New York: Soft Skull Press, 2022.

About the Author

Sean J Patrick Carney is an artist and writer in Gainesville, Florida. He is a recipient of the Arts Writers Grant and his essays and criticism appear frequently in Artforum, Art in America, High Country News, and other publications. Carney is currently an Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Studio Art at the University of Florida.

- 1Tsai, Eugene. “Robert Smithson: Plotting a Line from Passaic, New Jersey, to Amarillo, Texas.” Robert Smithson. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and University of California Press, Berkeley, 2004.

- 2Flam, Jack. “Introduction: Reading Robert Smithson.” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996, xxvi.

- 3Smithson, Robert. "A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites." Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996, 364.

- 4See Mancusi-Ungaro, Carol. “Authority and Ethics” in Tate Papers no.8, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/08/authority-and-ethics, accessed 27 November 2023 for a discussion of the work, which was owned by Andy Warhol who acquired it through an artwork exchange with Smithson.

- 5Nield, Ted. Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet. London: Granta Books, 2007, 66-69.

- 6De Camp, L. Sprague. Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. New York; Dover Publications, 1970, 54-56.

- 7Nield, 76.

- 8De Camp, 57-60.

- 9Blavatsky, Helena. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy, Vol. II - Anthropogenesis. Theosophical University Press, Pasadena, CA, 2019, 421. This ebook edition is a “a character-for-character, line-for-line reproduction of the two-volume 1888 first edition.”

- 10Brenson, Michael. “Art View: How the Spiritual Infused the Abstract.” New York Times, 21 December 1986, accessed 09 September 2023.

- 11Mosse, G.L. “The Mystical Origins of National Socialism.” Journal of the History of Ideas, Jan. - Mar., 1961, Vol. 22, No. 1, accessed 21 July 2023.

- 12Pearce, Michael. “From Universal Love to Nazism and Back.” MutualArt. 24 August 2022, accessed 10 August 2023.

- 13Robert Smithson Personal Library, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Among scores of scientific texts, Smithson’s library included Philip J. Darlington, Jr’s 1965 continental geologic study Biogeography of the Southern End of the World and L. Sprague de Camp’s sunken-site-debunking study Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. It should be noted that Smithson’s copy of Lost Continents was a 1970 Dover Publications edition, which would have been released the year after he was on Sanibel. However, the contents of Lost Continents had originally appeared as articles in science fiction periodicals including Galaxy, a title Smithson had copies of in his personal collection, and had been published in book form by Gnome Press in 1954. It is thus reasonable to assume that Smithson was aware of de Camp’s lost continent debunking efforts prior to procuring the 1970 edition from Dover Publications.

- 14De Camp, 49.

- 15Wilk, Elvia. Death By Landscape. New York: Soft Skull Press, 2022, 30-31.

- 16McCann, A.L. “Unknown Australia: Rosa Praed’s Vanished Race.” Australian Literary Studies, Vol. 22 Issue 1, May 2005, accessed 6 June 2023.

- 17Abrahams, Brad, dir. Telos or Bust. Austin, TX: Extrasensory Pictures, Inc, 2022, short.

- 18Wilk, 17.

- 19Castro, Teresa. “The Mediated Plant.” e-flux, issue #102, September 2019.

- 20Dewan, Pandora. “Florida's Projected Sea Level Rise by 2100 Is Bad News for Sunshine State.” Newsweek, 24 February 2023, accessed 17 July 2023.

- 21Einhorn, Catrin and Elena Shao. “In Florida, an Ocean as Hot as Bath Water Is Threatening the Coral Reefs.” New York Times, Section A, Page 11, 13 July 2023.

- 22Ibid.

- 23Smithson, Robert, “Insert Robert Smithson Hotel Palenque 1969-1972”, Parkett, Vol.43, 1995, n.p.

Carney, Sean J Patrick. "Florida, Man: Robert Smithson’s Hypothetical Continent in Shells: Lemuria." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 6 (January 2024). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/florida-man-robert-smithsons-hypothetical-continent-shells-lemuria.