Nancy Holt's "Dark Star Park"

Monument wars contesting public space. Controversies arising over renovations of Brutalist landscape design. As the custodian of a world-renowned artist-designed park now in its fourth decade, these recent developments resonate. The idea that public sculpture, parks, and plazas are subject to changing mores as manifestations of our collective identity has never been more evident.1

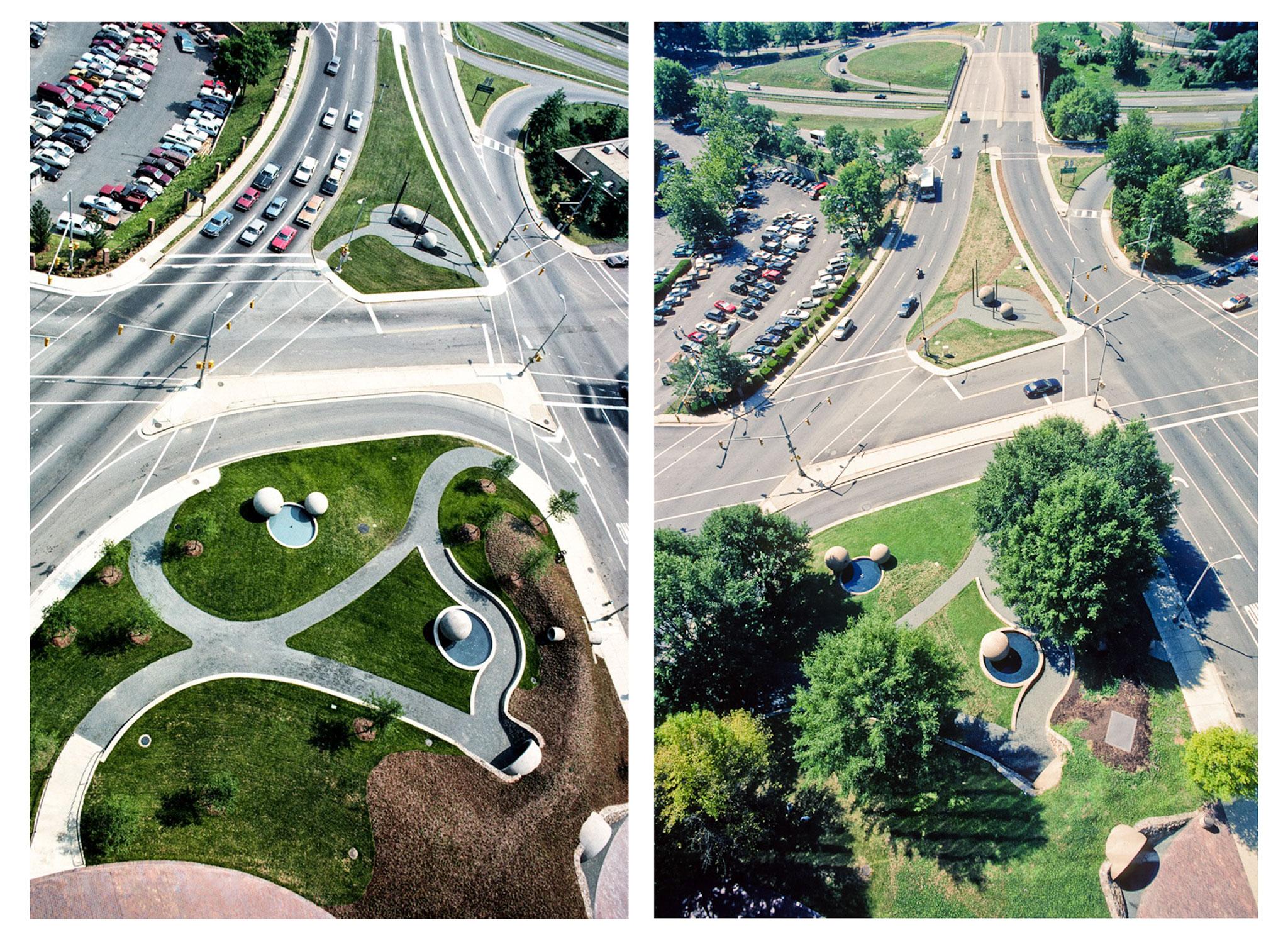

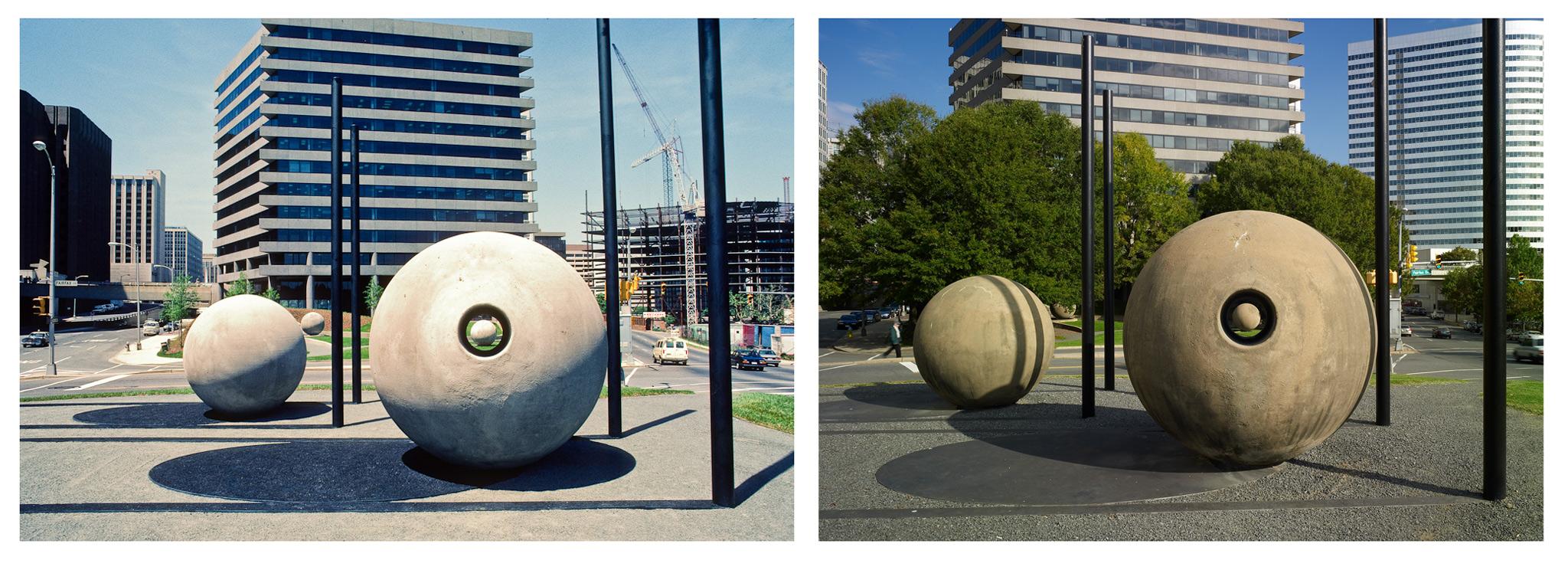

Arlington Public Art is the steward of Nancy Holt’s Dark Star Park, an urban park comprising two-thirds of an acre in the Rosslyn neighborhood of Arlington County, Virginia, located across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Commissioned in 1979 and dedicated in 1984, the work’s title refers to five large spheres—the most prominent feature of the park—that Holt likened to extinguished stars. The park has two distinct portions. The first of these is a shady side situated at the base of an office building, with two reflecting pools and a berm that deadens traffic sounds to form a tranquil oasis. The second is a sunny, traffic island portion that is activated by a solar event on the anniversary of the neighborhood’s founding.

By the late 1970s, the field of public art was retreating from placing abstract sculptures in barren plazas in favor of site-responsive projects. Land art was a familiar notion within both the art world and popular culture. U.S. cities were reimagining their potential and the role of public art in achieving this. Dark Star Park was a product of these factors. In 1978, Arlington County was awarded an $18,000 matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) Art in Public Places program to seed funding for a yet to be determined artwork in Rosslyn. NEA leadership at the time then connected Nancy Holt with the opportunity in Arlington.2

Holt, having recently completed Sun Tunnels (1973-76) in the Great Basin Desert, Utah, and Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings (1977-78) in Bellingham, Washington, was known for her remote works of art that marked the celestial orientation of a specific location. Constructing these environmental sculptures gave Holt the skills necessary to tackle an urban project where she saw herself as both artist and park designer.3 Dark Star Park’s planning took place during an era of urban renewal in major U.S. cities, and a time of expansive thinking for Arlington. Having successfully convinced the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority to underground the first five Metro stations in Virginia, Arlington then developed a land use plan that encouraged greater urban density near these stations. Rosslyn’s proximity to Washington, D.C.—without D.C.’s building height restrictions and with the soon-to-be Metro connection—made it a uniquely desirable place for commercial development.4

The opportunity for the new park began with a public easement granted to the County by a real estate developer in exchange for additional height and density in a planned office building nearby. This urban fragment was a former gas station site located at the southern tip of Rosslyn, just north of the iconic Marine Corps “Iwo Jima” Memorial. Though forlorn at the time, it was positioned as a highly visible gateway. There, Arlington saw the opportunity to create a symbol of the transformation that was taking place in Rosslyn in the form of a commissioned work of public art.5

I first met Holt in 1997, when the thirteen-year-old park needed its first renovation. The trees on the northern portion of the park had matured and offered considerable shade. However, the loose stone aggregate originally specified throughout the park was eroding with rainstorms and clogging the pools which no longer held water. An artist serving as park designer sets up many challenges for local government. Most park design is done by staff or contracted landscape architects who routinely replace outmoded functions and update design details. Having recently assumed responsibility for Arlington’s nascent public art program, I was in frequent contact with Holt during the five years it took to complete the restoration—the same span it took to create the park initially. Holt was concurrently completing Up and Under (1987-98) in Finland, working around her trips there to plan the Arlington repairs.

As in most public sector projects, compromise was necessary. Holt was asked to accept a semifixed aggregate, giving up the experience she wanted of walking on a yielding surface. This in turn allowed for sharper shadow outlines on the southern side of the park, where two spheres and four poles cast shadows that annually align with their markings in steel and stained concrete on the ground.6 August 1 was chosen by Holt to commemorate the day in 1860 that William Henry Ross acquired the land that was to become Rosslyn. 9:32 AM, the approximate time of the alignment, was chosen for purely aesthetic reasons; Holt once told me that she liked the length and direction of the site’s shadows at that time of day. Dark Star Park Day has become a tradition for area residents and office workers. Rain or shine they gather in anticipation of the solar performance. Minutes before it can appear implausible for a precise overlay or dodging partial clouds, followed by cheering and applause when it happens just as Holt planned.7

Since Holt’s death in 2014 Arlington Public Arts, which I direct, continues to champion the park’s design and determine which elements to repair or replace. Despite certain strong opinions, Holt didn’t attempt to control every element of the park as it aged, but embraced what time and visitors added to the piece. Cracks and leaching of mineral deposits in the cement spheres or desire lines cut across the sod by people passing through the park are such examples. Holt was insistent that the willow oak trees original to the park design, appearing as saplings in photos from the early 1980s, stay limbed up to enable the park’s characteristic site lines. A slip lane—connecting traffic from Fort Myer Drive on the west side of the park to North Lynn Street on the east side—was retired in 2019 to allow for an extension of the northern portion of the park. Exactly how this is realized will be a judgment call.

Holt’s careful approach to designing all elements of Dark Star Park set a high bar for subsequent public art projects in Arlington. We prefer an integrated approach where the artist serves as a member of the project design team, ideally in the position of defining the primary aesthetic for a new civic facility. We look to public-private partnerships to fund and maintain public art. We take advantage of long project delivery timelines to identify ways to expand project scopes and budgets. We require artists or their representatives to be present during installation to ensure quality control. Most importantly, Holt taught us to always support the artist’s vision.8

Thirty-six years after the dedication of Dark Star Park, Arlington is home to more than seventy permanent works of art. Arlington Public Art’s stewardship of the collection through interpretation, maintenance and programming has elicited greater public appreciation for these artworks as time goes on. How does a work of public art remain relevant when demands for governmental funding are myriad and community priorities and tastes change? It continues to reflect community values, just as Nancy Holt’s Dark Star Park has done for Arlington County.

Selected Bibliography

Beardsley, John. Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in the Landscape, 3rd ed. New York, London, Paris: Abbeville Press, 1998.

Cruikshank, Jeffrey L., and Pam Korza. Going Public: A Field Guide to Developments in Art in Public Places. Amherst, Mass.: Arts Extension Service, 1988.

Kwon, Miwon. One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge, Mass. and London, England: The MIT Press, 2002.

Lucy, Suzanne, ed. Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle: Bay Press, 1995.

Williams, Alena. Nancy Holt: Sitelines. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2011.

About the Author

Angela Anderson Adams is Director of Arlington Public Art, Virginia, and has worked as a curator and arts administrator for over thirty years, half of those directing Arlington Public Art. Under her leadership Arlington Public Art has grown from being one of the first developer-sponsored programs in the country to an internationally renowned, award-winning public and privately funded program. The program contributes art and design enhancements to most major civic projects undertaken in the County. Prior to working for Arlington County, Adams served as Adjunct Curator at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. and Exhibitions Director/Curator for the Arlington Arts Center, Arlington. She holds a B.A. in Art History from the College of Wooster, Ohio, and a M.A. in the History of Art from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- 1Gemma Tipton, “Up On A Pedestal: Repurposing Plinths as Public Art Space,” Irish Times, 6 July 2020; Jane Margolies, “At the Hirshhorn, a Battle Over Plans for Its Sculpture Garden,” New York Times, 16 July 2020 (updated 23 July 2020).

- 2The National Endowment for the Arts in 1974 changed its public art guidelines to encourage greater site specificity in the projects it sought to fund. By the late 1970s, earthworks and environmental art were added to the list of possible approaches and projects were encouraged to be more accessible and socially-beneficial by providing a public amenity. Kwon, pp. 56-69.

- 3Suzanne Lacy credits Holt as having “...set important precedents for public art in her teamwork with administrators and planning commissions” with Dark Star Park. The project also provided Holt the opportunity to create what is arguably her most physically accessible major sculpture. Lacy, p.240.

- 4“For more than 50 years, Arlington’s General Land Use Plan has served as a guide for the county’s smart growth journey. Arlington experienced a remarkable transformation from an auto-centric collection of neighborhoods to one of America’s most recognized examples of sustainability and transit-oriented development. Visionary planning began in the 1960’s as the D.C. metro area faced the impacts of suburban sprawl and accelerating reliance on automobiles. The region was preparing for the expansion of Interstate 66 and Metro when Arlington made a landmark planning decision to concentrate growth in mixed-use, transit centers. The “Bulls Eye” concept for the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor was an innovative decision that relocated Metro’s orange line away from the median of Interstate 66 to the commercial spine along Wilson and Clarendon Boulevards. The concept was reflected in the 1975 General Land Use Plan and, together with Jefferson-Davis [sic] Metro corridor planning, marked one of the earliest commitments by a suburban community to what is considered ‘smart growth’”. Arlington County website: https://projects.arlingtonva.us/planning/smart-growth/

- 5

In a letter from Arlington County Manager W.V. Ford to Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation Vice President Martin Atlas dated 28 June 1978:

“This project will include the first significant public open space in Rosslyn and the first major public art in Arlington. The sculptor will be selected by a six-person panel with the NEA and Arlington County each selecting three panelists.

“The County plans to place a permanent sculpture of monumental scale at a major entry to Rosslyn to mark it as a special place. The location, a 17,000+ square foot undeveloped urban park site, is situated along Arlington Boulevard, a major Northern Virginia entry to Washington, D.C. The park location provides an excellent view of the Iwo Jima Memorial and the Netherlands Carillon. In addition to the sculpture, the artist will be invited to help design the park in collaboration with the project director and the Park Division landscape architect. The site’s location at an important transportation junction near a major office center and proximity to two National memorials provides an exceptional opportunity for public art.

“We plan to design the park to complement the sculpture in order to create an environment that will attract people. The park will be developed in the near future and the County Board has set aside $150,000 for this project; this money does not include $36,000 in grants needed for the sculpture.”

- 6This prompted the need for Holt to calculate and then recalculate the astrophysical coordinates. In unveiling the project in 2002, we discovered—to our chagrin, in front of community members gathered to observe the annual alignment—that in our first attempt, the shadows were short by several inches. This problem was corrected by the time of the alignment in 2006. In a letter to the author dated February 21, 2002, Holt noted: “catching shadows is [a] precise endeavor.”

- 7

Other associations have come to be placed on the artwork, ones that Holt did not necessarily intend or anticipate. Each year we noticed that some attendees show up in tie dye shirts. We later learned that August 1 is Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia’s birthday and "Dark Star" the name of a well known song by the band. (Holt got a chuckle of this when I told her).

An informal tradition in most years, every five years beginning with the twenty-fifth anniversary of the park in 2009—the last time that Holt herself was present—Arlington Public Art has planned a major public event intended to keep the artwork in the public eye. In 2019, we worked with the Holt/Smithson Foundation and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden to organize a multi-day celebration in honor of the artwork’s thirty-fifth anniversary. This included a panel discussion, film screenings and an original site-specific composition commissioned to accompany the shadow alignment by Washington D.C. musicians Janel & Anthony.

Dark Star Park has inspired other artists to create temporary artworks in response. In 2006, Arlington Public Art commissioned Jack Sanders, Butch Anthony and Robert Gay & Lucy Begg/Thoughtbarn to create CO2 LED, a sculptural installation activating the southernmost tip of the traffic island side of the park. In 2013, J.J. McCracken composed and performed a 24-hour endurance work, the still point, which used the northern portion of the park as a stage set.

- 8

As might happen in any project stretching over five years to complete, Holt capitalized on the extended timeline to expand both her influence in the design of the park as well as support for the project. In exchange for delaying the park development by one year to allow the site to be used for construction staging for his adjacent multi-story commercial building, developer Joseph W. Kaempfer, Jr., both made a cash contribution to the future park project—increasing its budget—and invited Holt to participate in the design process for the building. After having successfully convinced the County to let her design the entire park as a work of art, Holt was able to reverse course on the initial orientation of the park serving as an entrance to Kaempfer’s building, and gain his permission to allow the park design to flow into the building itself. Continuing to find ways to grow the footprint for her project, Holt succeeded in convincing Arlington to seek permission from the Virginia Department of Transportation (who owned a traffic island to the south of the park site) to allow the park to expand to include a second component, visually connected to the original site.

The fact that Dark Star Park enjoys special favor within Arlington is in no small part due to the fact that Holt worked closely with numerous people from various public and private organizations over the five years needed to realize the project. This level of engagement allowed her to function as a consistent resource for the aesthetic goals of the project throughout its four-year planning process and later as a temporary resident of Arlington during its one-year construction period. Dark Star Park, the County’s first commissioned work of public art, was the inspiration for the County’s initial Public Art Policy which was adopted in 2000.

Adams, Angela Anderson. "Nancy Holt's 'Dark Star Park.'" Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts (September 2020). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/nancy-holts-dark-star-park