As for the spectator, he no longer expects to receive a ready-made experience, or the expression of an experience, but rather to participate at a deep level, either in his consciousness or, more physically, by immediate action. The artist no longer decides everything and projects it as a whole in some definitive and final composition; he now initiates a dialogue, or set of events…

— Roy Ascott

Hello. Welcome to the back room.

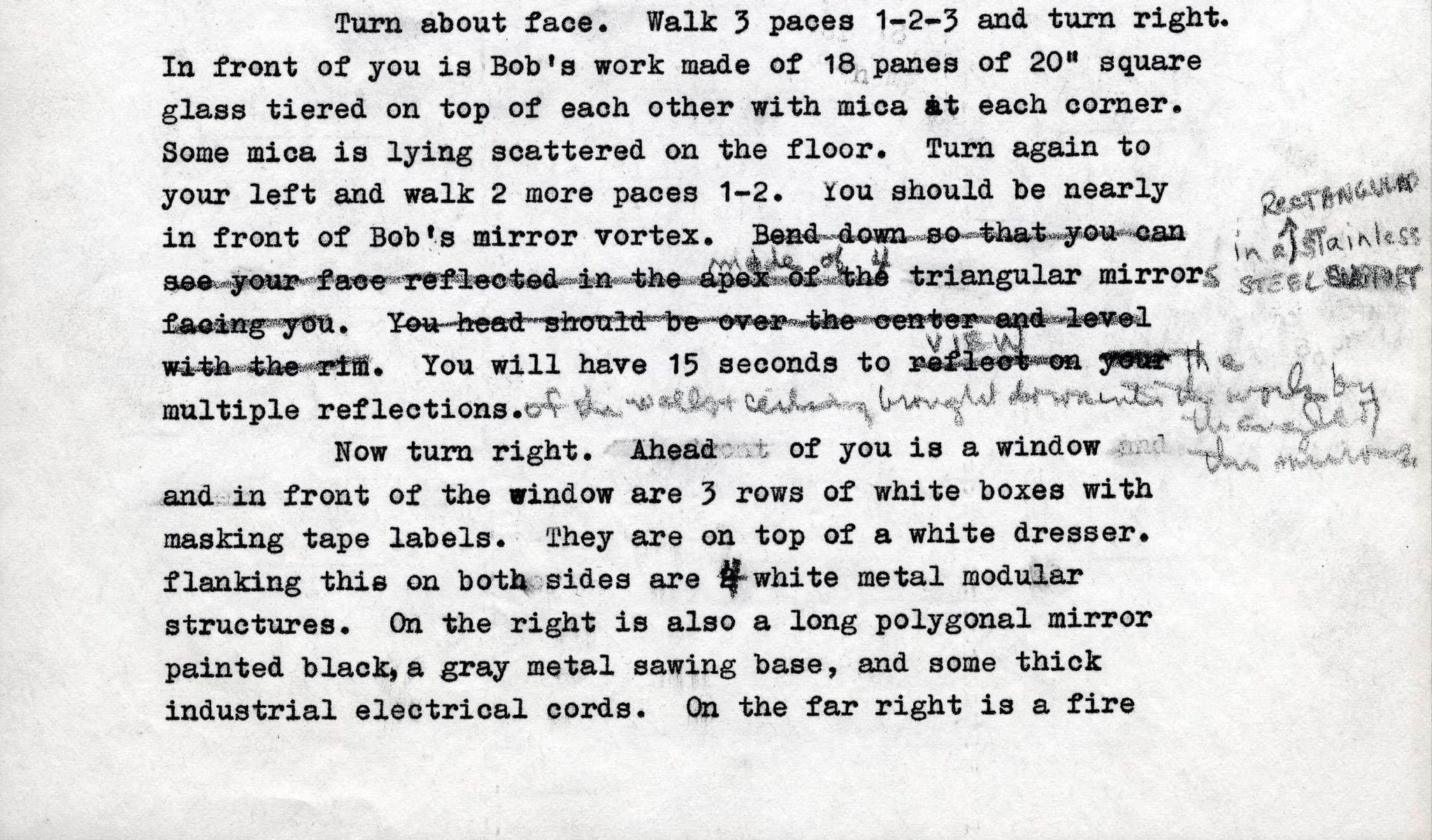

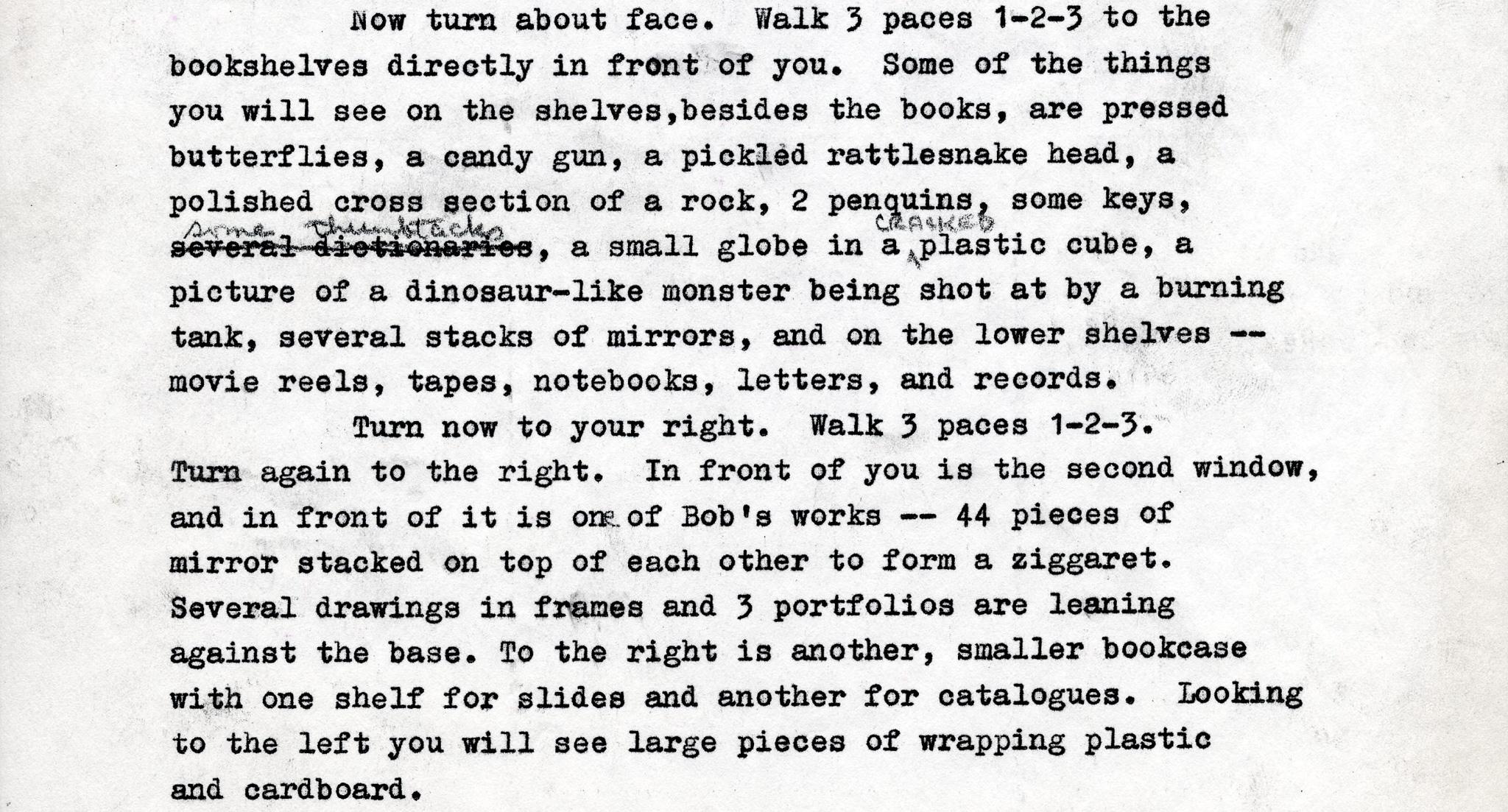

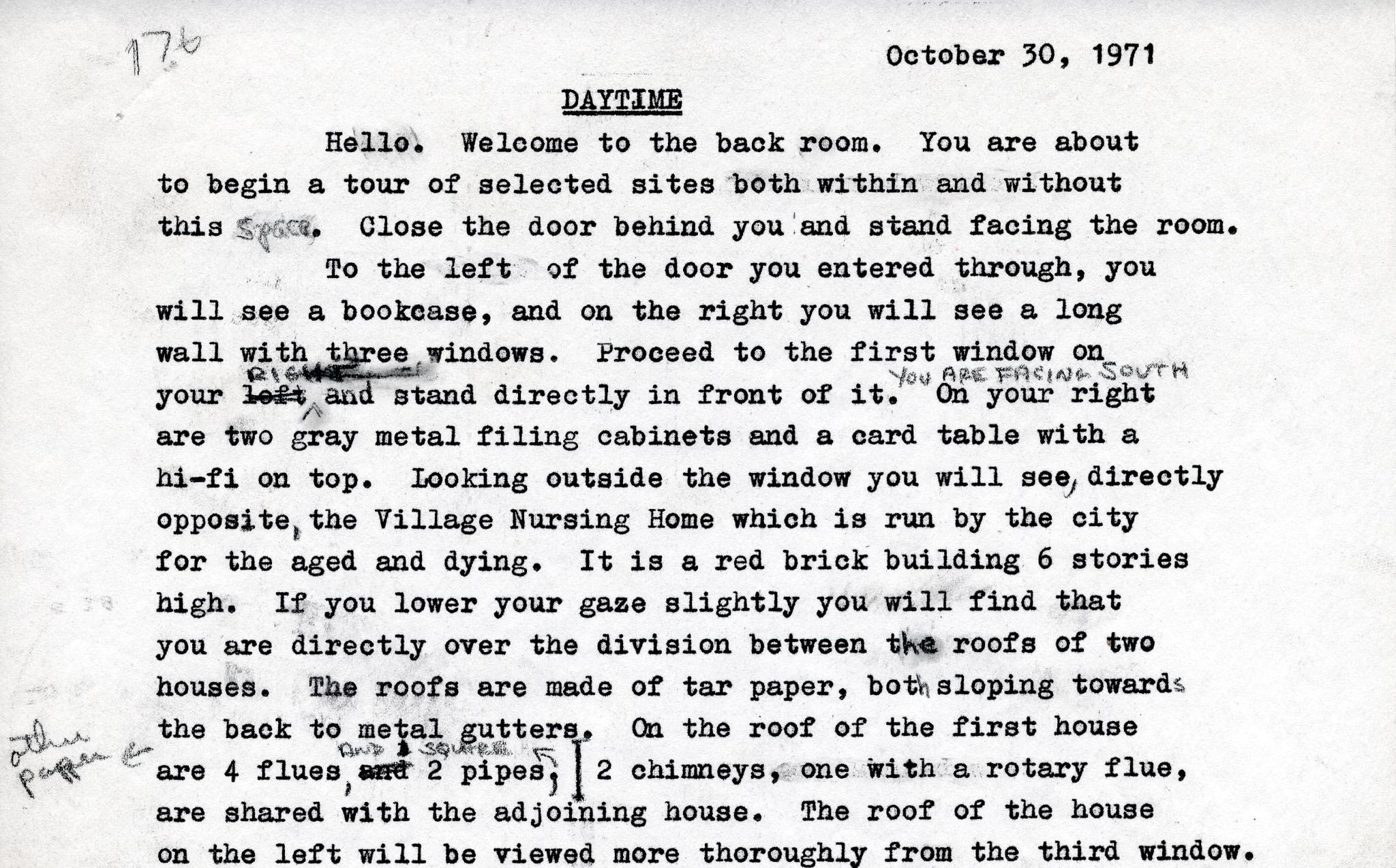

This simple greeting spoken in Nancy Holt’s calm, commanding voice is the opening of one of her earliest audio tours. Studio Tour: Daytime (two parts: October 30, 1971 and January 5, 1972; revised on March 29, 1972) sits at an interesting spot chronologically in Holt’s work incorporating sound. It was made after Stone Ruin Tour I and II (1967 and 1968), and before Tour of the John Weber Gallery (February 5–March 1, 1972). The Stone Ruin tours guided a small group of friends through outdoor space, while Tour of the John Weber Gallery was Holt’s first publicly exhibited tour. Studio Tour: Daytime exists in a wonderful in-between spot as it takes place on the safe ground of Holt and Smithson’s personal studio space, while incorporating some of the public, institutional components that appear in the work for John Weber Gallery.

At first listen, what is most striking about Studio Tour: Daytime is how it offers an incredibly diaristic look at Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson’s Greenwich Street studio with descriptions “of selected sites both within and without this space”

that include art materials, collected objects and ephemera, studio furniture, and even works by both artists. Some of the items hint at pre-existing works (such as “a map of part of the coast of Florida showing islands”

and “a large black and white map of the Great Salt Lake”

), while others hint at works to come (“movie reels, tapes, notebooks, letters”

). Holt is clearly taken with the energy of the studio space; her love for this personal, shared world and the potential for curiosity and creation vibrates throughout the score.

Linguistically, Holt’s tour alternates between imperative, command-giving sentences where she gives the participant instructions for navigating the space (“Now turn to your right. Walk 3 paces 1-2-3”) and declarative, descriptive passages where she draws attention to the elements inside and outside the space (“Several drawings in frames and 3 portfolios are leaning against the base”). This linguistic strategy makes sense with Holt’s choice of sound as her only medium. If she were standing next to the participant in a true guide/guided set-up, hand gestures, the turning of the head, glances, and even the simple movement of the guide walking would give the participant some direction. And in fact, Max Neuhaus did just this in his Listen walks at about the same time.

In 1966, a year before Holt’s first tour, Max Neuhaus initiated his series of Listen walks.

They took place at various locations throughout the United States and Canada, where Neuhaus would set a time and place for participants to meet him, then stamp the word LISTEN on their hand. He would then lead them on a planned walk, letting the sounds from the environment compose the work as participants moved through space. Neuhaus described the intent of these walks “to refocus people’s aural perspective.”

Like Holt’s audio pieces, the subject of these works was not a physical art object or even the sounds of either artist’s work, but rather the participant’s newly formed, temporally deepened awareness of an existing space.

In a similar vein, but as a counterpoint to both Neuhaus’ Listen works (with the artist silent, yet physically present) and Holt’s tours (with the artist speaking, yet physically absent), it is useful to consider a work by Giovanni Anselmo. In 1972, in the time and space of Arte Povera, Anselmo created his first Particolare work in Turin for his solo exhibition at Galleria Sperone. The work comprised a slide projector on the floor shining a single slide with the word “PARTICOLARE” (“detail” in Italian) into space, thereby naming the wall or person who walked in front of it a “detail” among the context of the entire space/experience/moment. Like both Neuhaus and Holt, Anselmo hoped to create a deeply present-tense consciousness of the existing space around the viewer, in his case by creating an awareness of part-to-whole that implies many elements working together within a physical, perceptual system. Unlike both Neuhaus and Holt, Anselmo the person is absent.

Yet, in Holt’s audio works, she is both there and not there. She is present through the sound of her voice—a considered, gentle tone—and not present physically. And she is both present and absent linguistically, as well. It is through her calibrated absence—as in many of her most poignant works—that she creates mental space for the participant as they navigate the studio. Over the course of the tour, Holt creates a situation where her voice weaves in and out of the listener’s consciousness—at times separate from it and at times merged with it. When she is giving commands (“Now turn about face”), she is separate—an extra, guiding awareness that has been in the space before. When she makes observations (“The roofs are made of tarpaper…”), she effectively merges with the ever-deepening inner psychology of the participant as she builds their consciousness of their physical surroundings detail by detail. In Roy Ascott’s prescient 1968 essay “The Cybernetic Stance: My Process and Purpose,” he describes this back and forth (or in Holt’s audio tour, her simultaneous presence/absence) as a situation where the spectator participates in the work “on the one hand, interacting with other people within a complex social situation, and on the other hand by conducting a private interior dialogue.”

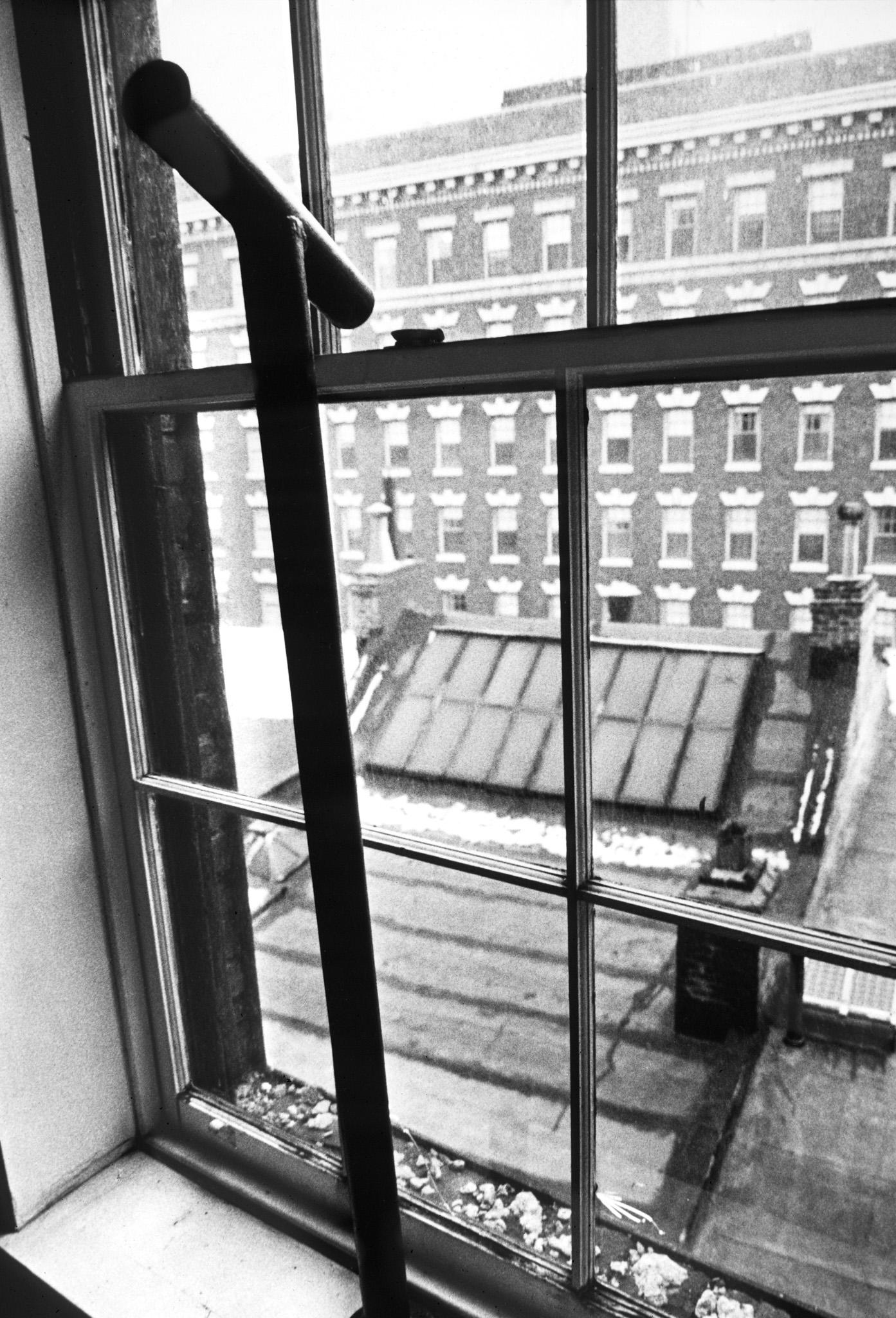

In Studio Tour: Daytime, Holt’s personal presence (the sound of her voice in her private space) plays an especially significant role. In a radical and rather poetic gesture, Holt directs the participant to experience one of her Locators and one of Smithson’s mirror works. She addresses the Locator work with the passage:

On the window sill is one of my works which is made out of 1 ½” black pipe. It is aimed at 2 windows of the Village Nursing Home. Look through it.

And for Smithson’s work:

You should be nearly in front of Bob’s mirror vortex made of 4 triangular mirrors in a rectangular stainless steel support. You will have 15 seconds to view the multiple reflections of the walls and ceiling brought down into the work by the angle of the mirrors. [Holt then makes fifteen snapping/clicking noises to count off the fifteen seconds.]

By encouraging the participant to interact with these sculptures, she inserts yet another consciousness into the scene—that of the artist who creates perceptual, experiential work (her own work or Smithson’s)—now embedded within her own experiential audio tour. In describing Tour of the John Weber Gallery, which also directs the participant to view other artist’s work, Holt frames this ‘artwork within an artwork’ (or ‘consciousness within a consciousness’) as a “tour where you looked closely at the environment […] and also looked at the other art in the gallery, including my East-West Locators, without giving any special emphasis because they were art.”

In this dynamic, Holt simultaneously occupies the role of art creator and art observer, while still framing the experience as an art guide. In thinking about other experiential work of this era, Miwon Kwon writes:

… the gift of sharing the authorial role of the artist, rendering the audience into active participants or partners to complete the work, registers the artist’s desire for solidarity or equality with his or her audience while at the same time reaffirming the artist’s superior position.

It is this choreographed unfolding of multiple, coexisting perspectives that gives the work its intricate psychology. And through the sound of Holt’s voice, this most personal space is transformed into both a generous act and a shared event.

Selected Bibliography

Cooke, Lynne. “Locational Listening.” In Max Neuhaus: Times Square, Time Piece Beacon, edited by Lynne Cooke and Karen Kelly, with Barbara Schröder, 29-43. New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2009.

Feulmer, Thomas, and Lisa Le Feuvre. Nancy Holt: Sound as Sculpture. Dallas: The Warehouse, Dallas, 2022.

Meyer, James. “Interview with Nancy Holt.” In Nancy Holt: Sightlines, edited by Alena Williams, 218–233. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Kelly, Caleb, ed. Documents of Contemporary Art: Sound. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2011.

About the Author

Thomas Feulmer is a curator, educator, and artist based in Dallas, Texas. Since 2004, he has worked at The Rachofsky House and The Warehouse, Dallas (both extensions of The Rachofsky Collection) where he is currently Curator. In 2022, he curated Sound as Sculpture, which featured the most comprehensive presentation of Nancy Holt’s audio work to date. Among his curatorial projects outside The Warehouse is Modern Ruin (co-curated with Christina Rees in 2011)—a two-day exhibition in a never-used WaMu bank building abandoned after the 2008 financial crisis. In 2024 he is co-curating (with curatorial advisor Lisa Le Feuvre) For What it’s Worth: Value Systems in Art since 1960 at The Warehouse, an exhibition exploring how artists generate, question, and infect value systems through their work.