30 Below

Inside, we observe nature as if through the wrong end of a telescope: the sky above appears detached; clouds pass as if on film. When occupied, the tower is converted into an observatory from which natural phenomena are contemplated as images, their own representation.

--Craig Owens, “Environmental Art,” Art at the Olympics, 1980

For years growing up, I would drive past Nancy Holt’s 30 Below (1979) wondering how this strange kiln ended up in the middle of an open field off a road that bypasses the town of Lake Placid, a locals’ short cut. The sculpture seems distinctly out of place: its lone red brick tower, punctured with apertures, does not seem at home with its surroundings, neither the small community garden nearby, nor the stand of maple trees that has taken over the field since Holt built the sculpture in 1979, nor the cluster of wooden structures of abolitionist John Brown’s farm nearby, nor even the dense and rugged Adirondack Mountains that surround it. Standing solitary in an open field bordered by forest, Holt’s large-scale sculpture evokes a ruin of another age.

30 Below’s thirty foot height and narrow oval openings summon a long history of architectural structures designed to order and control. It resembles a stone tower, battlement, or ancient grain silo, as one contemporaneous reviewer put it, noting the work’s roots in “human history.”1 Flanking the sculpture are two mounds of dirt, cloaked with grasses and wildflowers—Holt imagined these in her drawings as taking the form of the brick retaining walls. The mounds evoke a military trench or barrier, buttressing the tower to seem as if we are descending into it, as if the sculpture were buried into the ground below. Indeed, 30 Below’s title has often been described as referencing both the height of the sculpture, thirty feet, and the temperature during a Lake Placid winter, which can reach thirty degrees below Fahrenheit. But it also asks us to imagine that the pillar continues below the earth. Like many site-specific sculptures made in this period—by Mary Miss, Alice Aycock, Suzanne Harris, Robert Morris, and others—30 Below is an empty enclosure or architectural skin that calls to mind technologies of warfare, surveillance, or enclosure. Standing tall yet functionless, it is a quizzical tower, a fragment of a larger monument.

Holt’s alignment of the structure makes it seem all the more out place: its openings do not line up with the road so that, walking up to it, viewers are forced to move slightly to the right to enter it. Like Sun Tunnels (1973-76), the Locators series (1971-72), and Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings (1977-78), 30 Below is an instrument to observe a celestial order and the passage of time.2 Its top opens to the North Star, and the sculpture’s side arches are situated on North-South and East-West axes. Casting a shadow, it also functions as a giant sundial, a large-scale marker of time. Through these references, the sculpture makes palpable an abstract system that is not immediately obvious to those inhabiting the physical landscape. Holt forces us to reconcile the arbitrariness of viewing on the ground with an absolute, timeless order.3

Yet this sense of the sculpture as an abstract center falls away upon entering it. Once inside, the round brick walls dampen exterior sounds, muting the outside world. Traffic passing on the road, birds chirping in the meadow, wind blowing the maple trees: these noises become muffled and one can only hear clearly the sounds made by oneself or those one is with. The effect is an enforced intimacy or interiority, the feeling of being in one’s own body. The brick walls encircle the body as if an enclosure fitted out to its proportions, something Holt herself observed when she quoted Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space in a 1979 essay about Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings: “Seen from the inside, without exteriority, being can only be round.”4 Experienced from within 30 Below’s architectural skin, we can only be aware of our interiors and exteriors: the sculpture forms a blanket that encases the body, protecting it from the exterior contingencies of noise and weather. It is a shell scaled to its occupant, as Walter Benjamin writes of interiority: “The original form of all dwelling is existence not in the house but in the shell. The shell bears the impression of its occupant.”5

Inside the shell of 30 Below, Holt asks us to become aware of our senses in an acute way. With the larger soundscape of the world hushed—only some frequencies arrive through the narrow apertures—the intimate space of the enclosure forces attention on the body’s immersion in this confined space, or what Didier Anzieu calls the “sonorous envelope,” the immediate space that our bodies sonorously permeate.6 Looking up from this shelter into the oculus, we are observers of the passage of time. The sculpture’s round opening becomes an aperture to watch the movement of clouds and changes in light. From in here we look out there, watching an ungrounded moving image of the sky. Yet this effect is due to the collision of sense perceptions: “If vision always puts creatures physically constituted as we are in front of the world,” Steven Connor has written, “then sound…puts us in the midst of things. Sound puts us in the world from which vision requires us, however minimally, to withdraw.”7 By making us aware of sound and vision, Holt makes us observers of our own observations.8

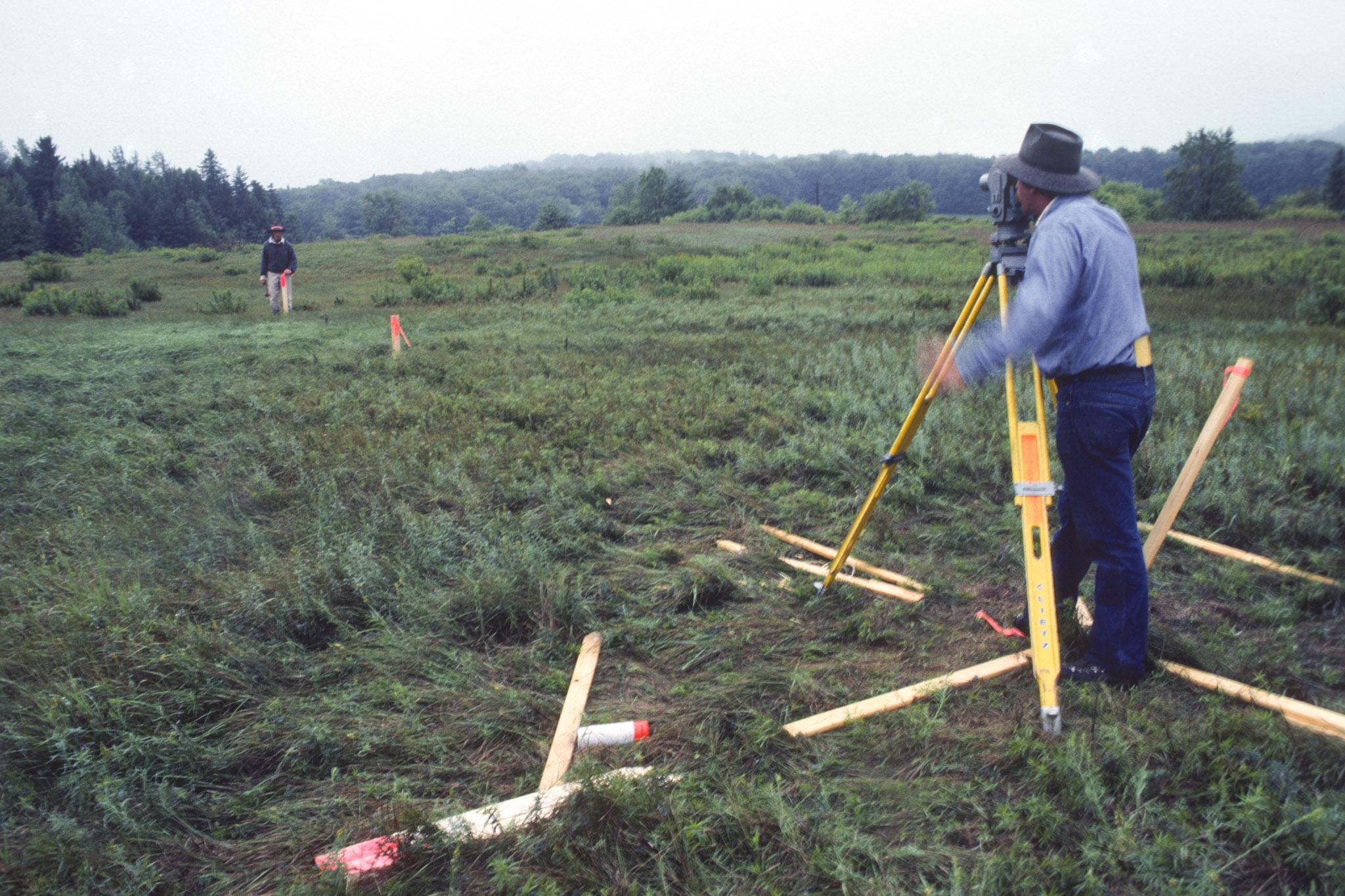

Holt built this sculpture for the 1980 Lake Placid Winter Olympics. That year, the National Fine Arts Committee organized an ambitious art program, responding to a mandate from the original 1908 charter that the Olympics would present exhibitions across the visual and performing arts—the idea was to merge art and sport, summoning classical ideals of the “total man.”9 While the 1980 exhibition jettisoned aesthetic idealism, the artists included in the show responded directly to the spectacle of the Olympics. Holt was one of eleven artists chosen by a jury to create works for the “environmental art” component—other categories included public sculpture, murals, performance, video, painting, crafts, graphics, sports photography, and children’s art. Environmental artists were permitted to choose their sites. The sculptures were envisaged to be temporary, but Holt’s was never dismantled.

Writing in his “environmental art” introduction in the Art at the Olympics catalogue, Craig Owens described how these sculptures address the category of landscape as both “a natural fact and a picture, as penetrable and accessible.”10 In many works, as in Holt’s, we are asked to see ourselves seeing, to encounter the frameworks that designate the aesthetic categories of landscape and site. Mary Miss’s Veiled Landscape took the form of a sequence of viewing platforms and screens that stretched down a hillside, in a path cut by utility companies; the work composes and recomposes views of the landscape as a pictorial image, as viewers look at the sculpture and through it.11 Siah Armajani (1939-2020) built Reading House in the town of Lake Placid, conjuring the house as both image—Quaker, vernacular and austere—and a space to occupy. Doug Hollis installed 800 orange wind vanes on tall aluminium poles on the grounds of a club, creating a spectacle of light, reflection, and color; as the wind changed direction, Kay Larson noted in her review, they darted “away in formation like fluorescent starlings.”

Holt’s 30 Below grounds vision in phenomenological terms, “solicit[ing] our physical bodies, our kinaesthetic and tactile responses,” Owens writes.12 This mattered for the context of the 1980 Olympics, with its high-tech seventy and ninety meter ski jumps that “project like Futurist rocket launchers from the bald top of a mountain” and its “eerie” luge and bobsled runs “lit with sodium vapor lamps so that at night they glow a sulphurous orange,” a scene Larson analogized to Apocalypse Now.13 What could be more different from this light and sound techno-spectacle than the experience of watching “clouds pass as if on film”? 30 Below lured in its audience with a hushed, intimate shelter—its habitable shell was an instrument to slow down and concretize perception of a cosmic scale.

Selected Bibliography

Art at the Olympics. New York: Andrew MacNair, Inc., 1980.

Holt, Nancy. “Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings, 1977-78.” Arts Magazine Vol. 53 No. 10 (June 1979): 152-55.

Larson, Kay. “The Expulsion from the Garden: Environmental Sculpture at the Winter Olympics.” Artforum Vol. 18 no. 8 (April 1980): 36-45.

Wagner, Anne M. “Being There: Art and the Politics of Place.” Artforum Vol. 43, No. 10 (Summer 2005): 264-269.

Williams, Alena J. ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

About the Author

Sarah Hamill is Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at Sarah Lawrence College. She is the author of David Smith in Two Dimensions: Photography and the Matter of Sculpture (University of California Press, 2015), and, with Megan R. Luke, co-editor of Photography and Sculpture: The Art Object in Reproduction (Getty Publications, 2017). Hamill has published essays on modern sculpture, the history of art reproduction, and contemporary photography, and is currently completing a book on 1970s feminist sculpture focusing on Mary Miss, Nancy Holt, Alice Adams, and Alice Aycock. She is the recipient of fellowships from the American Council of Learned Societies, the Getty Research Institute, and Villa I Tatti, the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

With support from Henry Moore Foundation

Holt/Smithson Foundation's Scholarly Text Program has been funded in part through the generosity of the Henry Moore Foundation Grants Program.

- 1Kay Larson, “The Expulsion from the Garden: Environmental Sculpture at the Winter Olympics,” Artforum Vol. 18 no. 8 (April 1980), 44. Holt used local materials to build the sculpture, including brick kilns in Lake Placid. She hired Al Poynter to build the sculpture; Poynter also built Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings, a sculpture on the campus of Western Washington University. See Lucy Lippard, “Tunnel Visions: Nancy Holt’s Art in the Public Eye,” in A. J. Williams, ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines, n. 8, 70.

- 2Anne Wagner likened Sun Tunnels to a camera that records the passage of celestial time. Anne M. Wagner, “Being There: Art and the Politics of Place,” Artforum Vol. 43, No. 10, (Summer 2005), 267.

- 3Hal Foster describes Holt’s Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings similarly. Hal Foster, “Review [Nancy Holt, John Weber Gallery; Tony Smith, Pace Gallery; Alain Robbe-Grillet and Robert Rauschenberg, Castelli Graphics],” Artforum Vol. 18 No. 1 (September 1979), 72-73.

- 4Nancy Holt, “Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings,” Arts Magazine Vol. 53 No. 10 (June 1979), 152-55, reprinted in Alena J. Williams, ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 98.

- 5Walter Benjamin, “The Interior, The Trace,” The Arcades Project Trans. H. Eiland and K. McLaughlin (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 1999), 220.

- 6Didier Anzieu as quoted in Steven Connor, “Ears Have Walls: On Hearing Art” (2005), in Caleb Kelly, ed. Sound: Documents of Contemporary Art (London and Cambridge, Mass: Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press, 2011), 134.

- 7Connor, “Ears Have Walls: On Hearing Art,” 135.

- 8This is Pamela M. Lee’s phrase. See Pamela M. Lee, “Art as a Social System: Nancy Holt and the Second-Order Observer,” in A. Williams, ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines, 41. Holt refers to this as the “concretization of perception.”

- 9National Fine Arts Committee, “Introduction,” Art at the Olympics (New York: Andrew MacNair, Inc., 1980), 2.

- 10Craig Owens, “Introduction: Environmental Art,” Art at the Olympics, 6.

- 11Ibid., 5

- 12Ibid., 10.

- 13Larson, “The Expulsion from the Garden: Environmental Sculpture at the Winter Olympics,” 38.

Hamill, Sarah. "'30 Below.'" Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 2 (September 2020). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/30-below-0.