“We live in a world of steel mandalas” — Nancy Holt’s "Electrical Lighting for Reading Room"

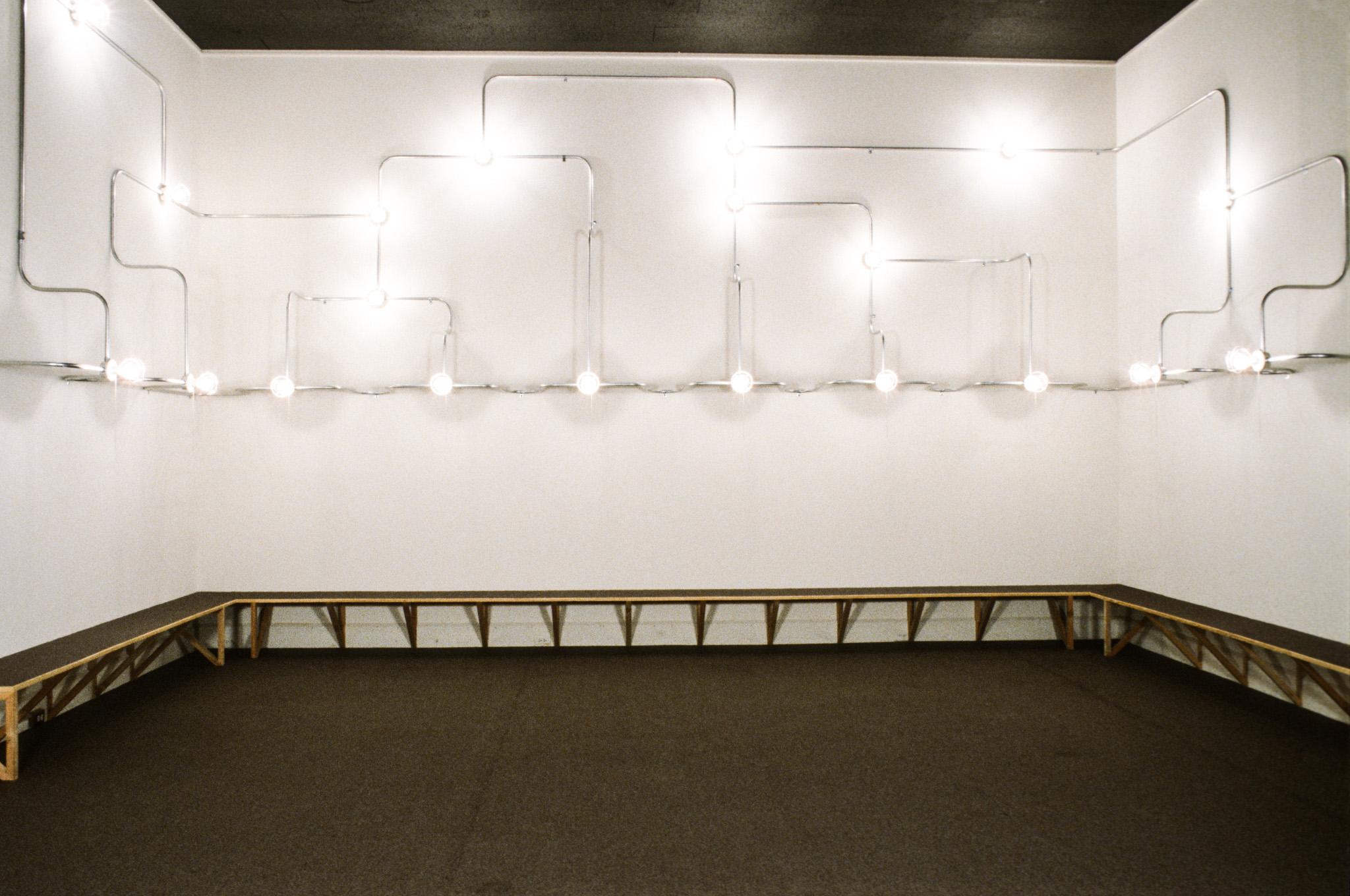

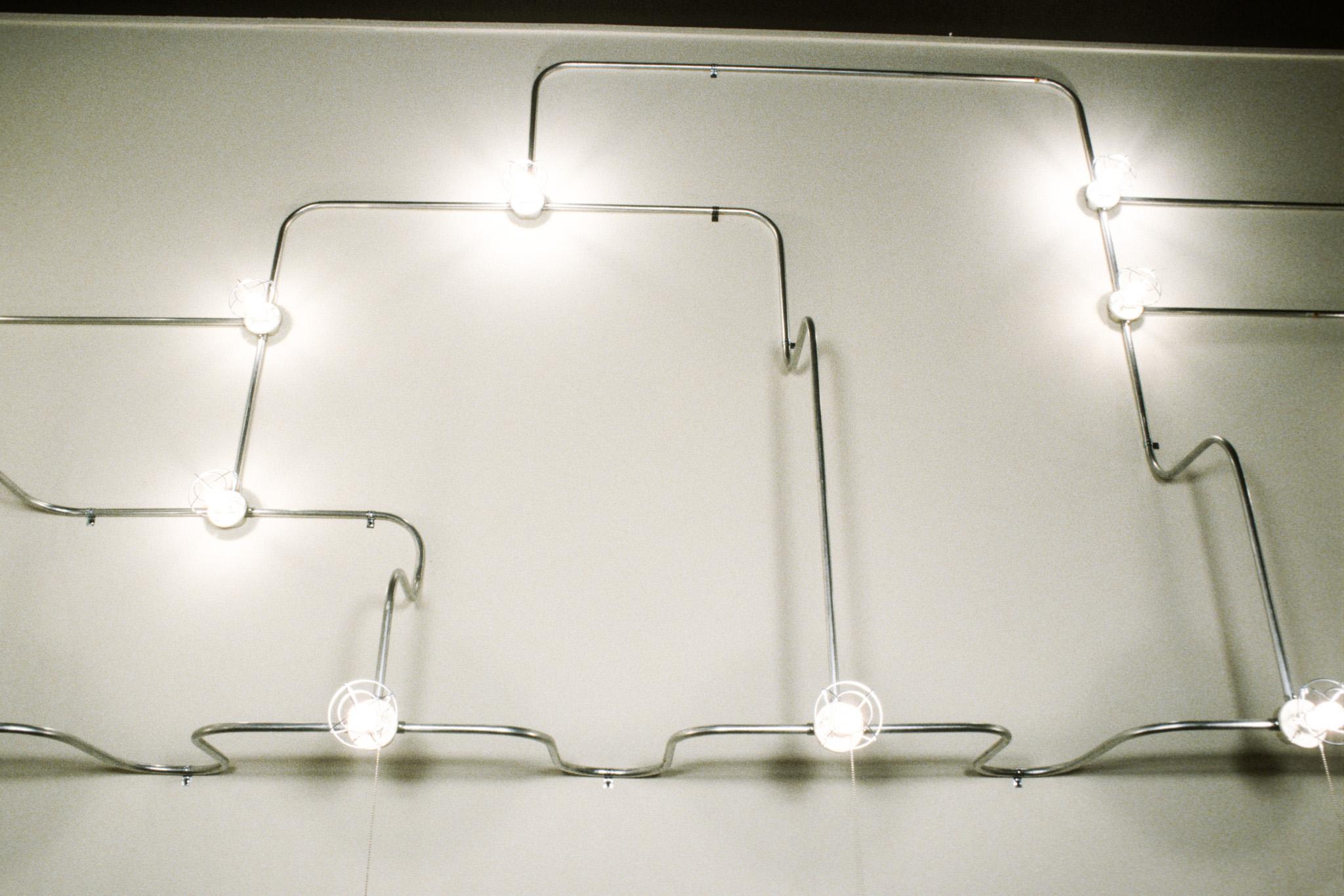

A defined interior space with white walls contains an arched network of steel pipes that undulates along three walls of the room. Each connection point of the protruding network is marked by twenty standard white ceramic sockets that holds a lightbulb, protected by a metal cage. From the bottom row of ten lightbulbs dangle chains, which can be pulled to turn them on and off. Below the grid is a continuous low bench for sitting.

This is Nancy Holt's Electrical Lighting for a Reading Room from 1985. Several of Holt’s own texts begin with a description of how the work was made, followed by a clear outline of what you see on encounter, a simple method offering an invitation to remain present with the artwork. Electrical Lighting for a Reading Room is a functional sculpture, part of a series Holt termed System Works that reveal the mechanics of everyday technological structures for the circulation of electricity, heat, water, and air. This particular work exposes something so common to contemporary life that it is often forgotten: light.1 In all the System Works, Holt created a site responsive outline in drawings and then collaborated with tradespersons2 to execute the sculpture, deferring to their expertise. By revealing what is hidden and taken for granted, Holt ask us to connect ourselves to the world around us and travel further to what lies outside the walls.

Nancy Holt consistently investigated how we perceive our surroundings, as she described: “My work involves making structures that focus perceptions, channeling them and giving them a depth we don’t otherwise have an opportunity to experience. I’m primarily interested in people perceiving their own perceptions.”3 Electrical Lighting for Reading Room is modest in its appearance, it provides a space for concentrated reading—as she once wrote, “I want to build things that people feel good about getting inside of.”4 Holt's work shapes awareness of the immediate surroundings and, in the same breath, transports you out into the world through your own actions. It is in this context of perception and the surrounding environment that the title of this essay should be understood: "We live in a world of steel mandalas.“ A mandala is a geometric configuration of symbols that can be used to focus the attention of spiritual practitioners in particular. Again, this is about perception, which Holt links to the built environment around us.

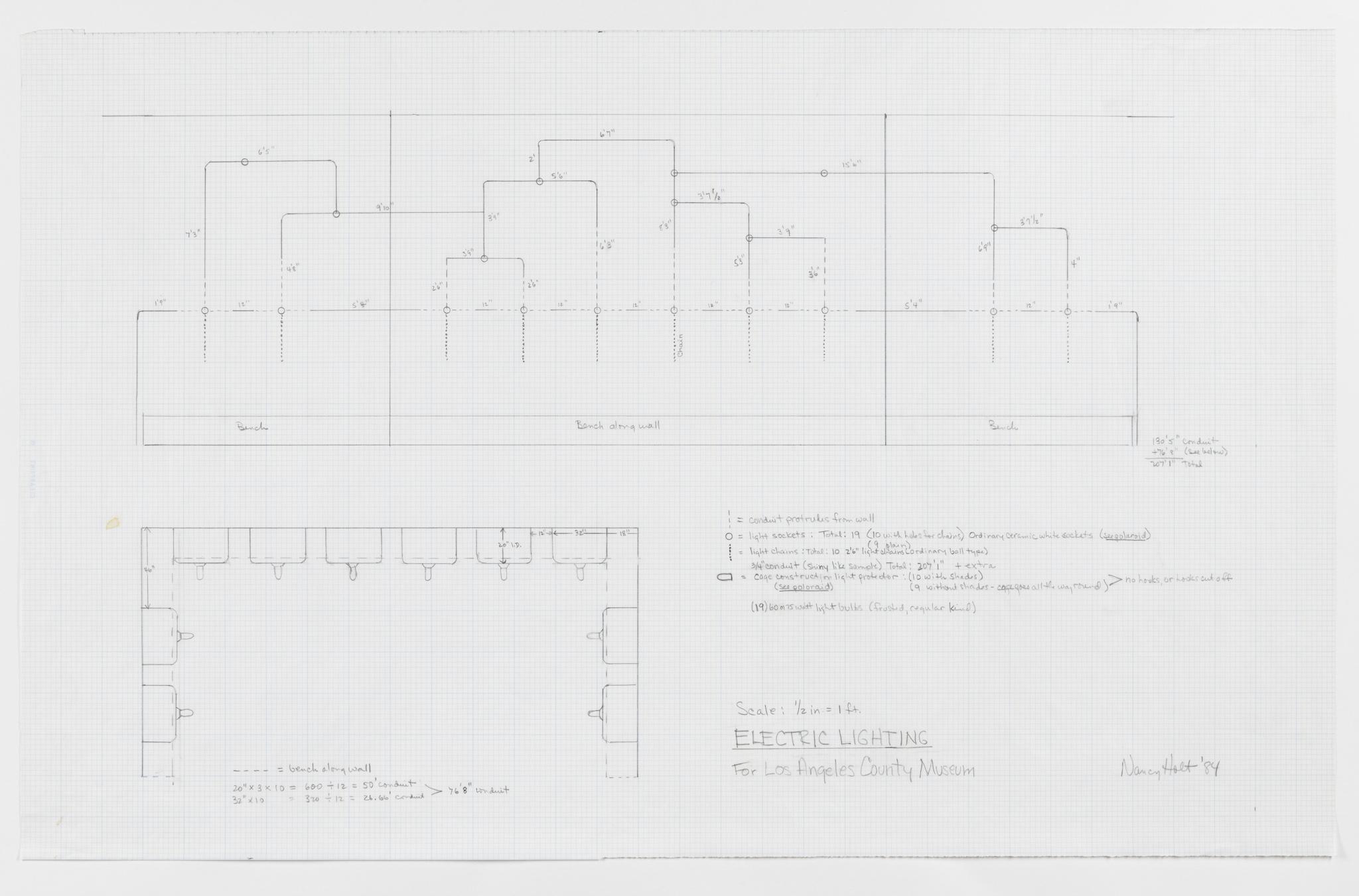

In 1984, a year after this statement, Holt was commissioned to “design specific installation components”5 for the exhibition The Artist as Social Designer. Aspects of Public Urban Art Today at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). She was invited to think about the reading area of the exhibition, which presented documentation of urban outdoor art that could not be presented as original sculpture in the interior gallery. Holt's proposal, Electrical Lighting for Reading Room,6 responded to the museum's concept of exhibiting works that consider “innovative solutions to familiar problems”7 —artistic practices that were aesthetic and functional, and that addressed sociological references. Holt’s technical drawings from 1984 for Electrical Lighting for Reading Room lays out a structure of circuits for three walls on graph paper,8 including a large elevation view and smaller bird's-eye view, both with precise dimensions and list of standard industrial materials. While responding to the invitation to be functional and provide a space for reviewing the exhibition's reading materials, Electrical Lighting for Reading Room also raised a sociological question. In Holt's own words: “technological systems have become necessary for our everyday existence, yet they are usually hidden behind walls or beneath the earth and relegated to the realm of the unconscious. We have trouble owning up to our almost total dependence on them.”9 Holt makes a system visible that is usually forgotten or overlooked. As she beautifully puts it, “What I often call my ‘system sculptures’10 are not things in themselves that begin and end in a gallery or outdoor site; they’re a part of a huge network of interconnected conduit systems often deep within the ground or in the walls of buildings. Natural elements flow through these systems, and I build a work that continues the flow and makes it visible and more conscious.”11

Consistently the innovations that occur during periods of industrialization and technological development impact everyday life. In the nineteenth century, during the introduction of gaslight, it seemed to contemporaries that industries were “were expanding, sending out tentacles, octopus-like, into every house. Being connected to them as consumers made people uneasy.”12 But such resistance to centralized energy faded with the invention of the lightbulb. In addition to being clean and safe, electricity transformed lighting from an individualistic service to a collective system. In line with Holt’s thinking, a note from 1883 seems striking: “However perfect a lamp may be, taken by itself it is not a complete lighting system. It is only one part of the whole system. One does not fill a lamp with electric current like oil.”13 Lights powered by electricity are connected to a larger system, which is perhaps most apparent when it fails, as in a blackout. Electric Lighting for Reading Room points to this individual act of turning on a light being connected to an expansive system. Being present with the artwork is to be bathed in light, often in the company of others within the space, while being connected to a system using resources.

Holt explicitly addressed the issues of ecological concerns and perceptions in many of her works—topics central to technology and power. Turning on a light initiates a connection to the power grid, which is powered by exploiting natural resources. Holt invites us to physically trace a relationship to elements that usually remain unseen, and asks us to become more sensitive to our use of energy. In her own words: "Reflecting on how our basic technological systems have interacted with nature reveals that in the name of technological improvement the environment has frequently been blindly and carelessly damaged. While continuing to meet our immediate material needs, the channeling of the energy and elements of the earth can be done intelligently with the long-term benefit of the planet in mind. In doing so we become nature’s agents rather than nature’s aggressors.”14 Holt was visionary in her thinking about the ecological aspects of her work.15

More than forty years after Electrical Lighting for Reading Room, we live in a yet another system that obscures the responsibility of one's own actions, while entangling us in a vast and incomprehensible network. In the age of the Internet and Artificial Intelligence (AI), we grope in a grid that undulates in incomprehensible patterns. Just as we have probably never visited the power station that supplies our electricity, it is hard to retrieve the true source of information we receive online, and we often cannot trust the information on who actually thought or wrote or said what. The paths of information are interconnected and get lost in the digital swamp. To make matters more intense, AI programs are often incomprehensible, even to experts. So often we think “the light just goes on” without knowing the path of the power source. The direct logic of pulling a string to turn on a light is a comprehensible action, but when surfing the surfaces of information and poetry the source is harder to understand. With every tap of the keyboard, we leave a trace and consume resources. AI is one of the most energy-intensive modern endeavors.16

With a historical mindset in her own time, Holt remarked, "We use water and electricity so indiscriminately; we just don't think about it. You turn on a light switch and the light is there, but it's only been there for a little over a century. The history of technology is also part of what I was doing with systems in the early '80s. (…) as an artist, I could bring more awareness to them.”17 What makes Electrical Lighting for Reading Room so relevant today is that Holts reminds us that we interare, that we are inter-connected and inter-dependent on all elements around us. The term “interare” is borrowed from the thinker Thich Nhat Hanh, who considers that interconnected nature of all beings. For him, there is no independent self – indeed, the perception of self, of “me”, of “mine” is all an illusion. Considering the world through the idea of interbeing underlines how we are deeply connected to each other, to our planet and to all things. We cannot be alone, we can only interbe. Nhat Hanh’s concept of interbeing echoes in the current age, in which humans have become the dominant force shaping Earth’s bio-geophysical processes18 as well as the awareness of our entanglement with our surrounding beyond the supremacy of humans19 and in light of our contemporary global connectivity. Turning on a light switch or retrieving information requires action on our part. An extensive system of preparation, cables, and resources is required for the light to come on, and for words or images to reach us. We believe cannot “be” in our current times without these backstage systems, but we cannot “be” without care of environment—we are with it, in it, and always dependent on it. It is with us, and we are with it. Nancy Holt's installation shows us this by making us think about the scope of our actions through a simple gesture. This is the power of Electrical Lighting for Reading Room.

Selected Bibliography

Alena J. Williams, Nancy Holt: Sightlines (Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press, 2011).

Nancy Holt, “Ecological Aspects of My Work,” first published in 1993 in the exhibition guide for Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues, edited by Gail Gelburd.

“Systems: A Conversation with Nancy Holt,” interviewed by Joan Marter, October 1, 2013.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch Disenchanted Night. The Industrialization of Light in the nineteenth century (Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press,1984).

About the Author

Dr. Clara Meister is a writer and curator fascinated by language and music, and she wrote her dissertation on the human voice. Meister is co-founder of the exhibition collective SOUNDFAIR, was curator of the MINI/Goethe Institute Curatorial Residency Ludlow 38 in New York, curated the performance program for the Marrakech Biennial MB5, and is co-founder of the online magazine ment. She has worked at the Gropius Bau in Berlin as Associate Curator to the Director’s Office, project lead of the Program on Artificial Intelligence, and curator, where she co-curated with Lisa Le Feuvre Nancy Holt: Circles of Light in 2024. She is currently the director of the Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin.

With support from Henry Luce Foundation

This Scholarly Text is supported by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to further our public-facing research into the art and ideas of Nancy Holt.

- 1This series started in the early 1980s, with Holt investigating electricity—see William T. Carson Electrical System: An Archaeology of an Artwork (accessed August 8, 2024.)

- 2See Lucy Lippard’s definition of conceptual art: “Conceptual art, for me, means work in which the idea is paramount and the material from is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious, and/or ‘dematerialized.’” Lucy Lippard in Catherine Morris and Vincent Bonin (editors) Materializing "Six Years.” Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2012).

- 3Nancy Holt in Ted Castle Art in Its Place, Geo, September 1982: 75, 112.

- 4Nancy Holt, “Nancy Holt Interviewed by Micky Donnelly.” Interviewed by Micky Donnelly, CIRCA, no.11 (July-August 1983): 4-10.

- 5Maurice Tuchman in The Artist as Social Designer. Aspects of Public Urban Art Today (California, USA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art,1985), Exhibition catalogue, exhibition on view February 7 - March 17, 1985.

- 6Initially Holt titled the work Electrical Alcove in her early drawings, and then settled on the title Electrical Lighting for Reading Room.

- 7Cf Tuchman.

- 8The benches at LACMA were made by Scott Burton (1939-89), and titled Seating and Table Elements for Reading Room. Holt/Smithson Foundation notes that each presentation of this work requires seating furniture to be located directly under the sculpture, with its design determined by the presenting institution.

- 9Holt noted of another System Work, Ventilation System: “Along with being evocative of a technological system, I intend the work to be practical yet playful, functional yet not really necessary, a part of the architecture yet part of the outdoor environment as well.” Nancy Holt “Ventilation Series” in Alena J. Williams, Nancy Holt: Sightlines (Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press, 2011) 144. Originally published as “Nancy Holt: Ventilation Series” in Christina M. Strassfield, Volume 6 Contemporary Sculptors, exhibition catalogue, unpaginated (East Hampton, N.Y.: Guild Hall Museum, 1992). The System Works call attention to functionality and are not always actually functional.

- 10Holt later fixed the term “System Works” as the name of this artwork typology.

- 11Nancy Holt “Systems: A Conversation with Nancy Holt,” interviewed by Joan Marter, October 1, 2013, accessed August 10, 2024, https://sculpturemagazine.art/systems-a-conversation-with-nancy-holt/.

- 12Wolfgang Schivelbusch Disenchanted Night. The Industrialization of Light in the nineteenth century (Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press,1984), 29.

- 13Partille, as quoted in Wolfgang Schivelbusch Disenchanted Night. The Industrialization of Light in the nineteenth century (Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press,1984), 76.

- 14Nancy Holt “Ventilation Series” in Alena J. Williams Nancy Holt: Sightlines (Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press, 2011) 144. Originally published as “Nancy Holt: Ventilation Series” in Christina M. Strassfield, Volume 6 Contemporary Sculptors, exhibition catalogue, unpaginated (East Hampton, N.Y.: Guild Hall Museum, 1992).

- 15Cf. Nancy Holt “Ecological Aspects of My Work,” first published in 1993 in the exhibition guide for Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues, edited by Gail Gelburd.

- 16Cf. Ariel Cohen: AI is Pushing the World toward an Energy Crisis, May 23, 2024, accessed August 9, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/sites/arielcohen/2024/05/23/ai-is-pushing-the-world-towards-an-energy-crisis/.

- 17Nancy Holt “Systems: A Conversation with Nancy Holt,” interviewed by Joan Marter, October 1, 2013, accessed August 10, 2024, https://sculpturemagazine.art/systems-a-conversation-with-nancy-holt/.

- 18An epoch often discussed under the term Anthropocene, which in itself in the recent years has received various philosophical updates and critics fostering the human dominance without including the codependency with the surrounding.

- 19For this concept the influential thinker Donna Haraway created the widely referred neologism Chthulucene.

Meister, Clara. "'We live in a world of steel mandalas' Nancy Holt’s Electrical Lighting for Reading Room" Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 7 (October 2024). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/we-live-world-steel-mandalas-nancy-holts-electrical-lighting-reading-room.