Spinwinder (1991)

In a moment captured in a photograph at the start of the twentieth century, in the knitting room of the New Bedford Textile School, three students stand at individual machines. Each holds a circular creel from which spooled yarn was drawn up, then down, through a mechanized system that knits a tubular shape. I encountered this image in the archives of the Claire T. Carney Library at UMass Dartmouth, where I worked from 2017 until 2022 in a lecturer position, configured to combine teaching and curatorial work (later with the title Director of Community Engagement Initiatives). In my first days on campus, I was amazed to discover the presence of Nancy Holt’s Spinwinder (1991), a prominently placed large-scale sculpture that, nevertheless, seemed to remain marginal within the greater campus imaginary. While faculty, staff, and alumni shared cherished personal stories from the time of its arrival on campus—remembering Holt’s visits to campus, and a student protest over funding allocations that centered Spinwinder in direct action interventions—the great majority of current students in my Processing Place seminar could not identify the work from a slide on the first day of class. “It looks familiar,” I would hear. “I’ve seen it before.” Or: “I know where that is, but I don’t know what it is. Is it piping for heating?” Over five years, this first day of class discussion shifted as my students, colleagues, and other collaborators reinvigorated our relationships with this place-specific artwork through research, public programs, and an exhibition.

Spinwinder echoes the form of the knitting machines documented at the nearby textile school nine decades earlier. The sculpture’s relationship to New Bedford textile history and machinery is core to its conception as one of Holt’s most personal works. Spinwinder was proposed for the Percent for Art Program of the Massachusetts Art in Public Places Program as a “tubular sculpture consisting of a central movable cylinder and 10 ft. high inner arches expanding into 18 ft. high splaying tubular elements. Beneath the central surface of the artwork are buried certain artifacts relating to the textile industry of southern Massachusetts.”1 Its form today honors this vision. Its six steel-wound spools surround and connect through arched tubes to a central cylinder mounted on a circular track. With some physical effort, and some loud squeaking (less, following recent conservation), both the spools and the central cylinder can be rotated. People often emerge from its center remarking that the sculpture seems larger inside than they expected after looking at the work from some feet away. I suspect that the energy expended within the work may contribute to a sense of its growing scale, and I think about the human effort involved in the operations of weaving machines (and maritime vessels) of the regional industries that Nancy Holt pointed to in her proposal for Spinwinder.

Holt’s connection to this local history runs deep. Her grandfather, Samuel Holt, was the head of the Department of Designing at the New Bedford Textile School, one of the institutions that eventually became consolidated into Southeastern Massachusetts University (SMU), the commissioning entity for Spinwinder. The school became UMass Dartmouth the same year that Holt’s sculpture was completed. Samuel Holt taught students to use Jacquard looms, weaving devices using proto-computing systems with coded cards to manifest design patterns. At the time, New England—and eastern Massachusetts in particular—was a center for textile production thanks to its proximity to waterpower, capital, technological innovation, and the power of the major metropolis of Boston. In the Quarterly Journal of New Economics in 1980, John S. Hekman2 noted how in this place, and at this time, “machinery was essentially custom built and rebuilt for the mills” in a cycle of economic and innovative reinforcement. We can understand New England textile mills as phenomena of industrial reification—site-specific in their customized machinery, and necessarily place-based through embeddedness in local economic patterns.

Spinwinder likewise possesses a complex relationship to its context. In formulating her own evolving differentiation between site- and place-based art, scholar Lucy Lippard has looked to Spinwinder on multiple occasions. In the 1997 publication The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, Spinwinder is pictured on a page facing Lippard’s observation: “It is a lot easier to make locally meaningful art in a place than on a ‘site.’”3 In other words, making work in, and about, place demands a more sustained effort at knowing and addressing the “locally meaningful” and layered historical, social, and ecological attributes of a location. Lippard illustrates Spinwinder’s engagement of these matters through an extended caption explaining Spinwinder’s references to Holt’s grandfather, demonstrating a personal connection to place.4 In Lippard’s later essay “Tunnel Visions” in the Sightlines volume, published in 2011, Spinwinder returned as an example of work “inspired by human experience” and local history, though here Lippard adds: “For the most part, however, Holt’s work is more often site-specific than place-specific. She takes the site into consideration in various ways, addressing its topography, its history, its local materials, its place meant on the planet in relation to the surrounding universe.”5 Spinwinder is a rare example of personal relationship to place within Holt’s oeuvre. Lippard reflected over email correspondence: “Spinwinder seems to be the only truly personal piece of hers that I can think of,” and, “Most of her work was site-specific rather than place-specific, unless astronomical locating counts as place, not site.”6 Spinwinder, with its special relationship to place, stands out among Holt’s public sculpture—while also remaining aligned with Holt’s ongoing ideas about cyclical time, her interest in industrial history, and her work on New Bedford history and family in more intimate artistic media.

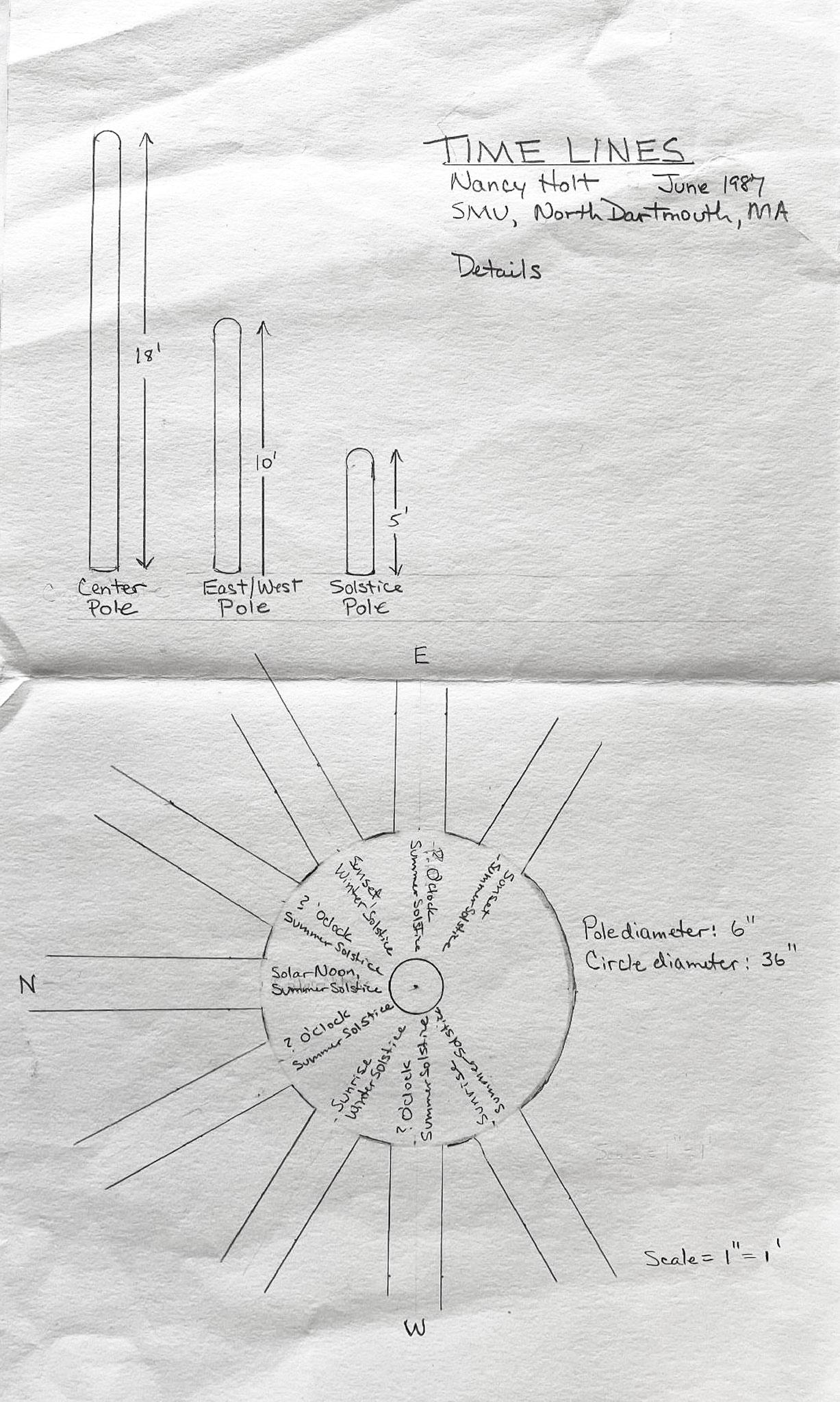

Holt’s complex relationship to New Bedford as a convergence of “kin” and “place” (her language, when writing about her Aunt Ethel in the 1980 artist book Ransacked) had important conceptual parallels with her approach to “distancing” and perceiving place in other media and sculptural works.7 Accordingly, both the place and the site of UMass Dartmouth’s campus were factors in Holt’s Spinwinder design. Former facilities manager William Traubel, who worked with Holt on adapting the proposal for the campus, recalls an early concept with a vertical element that he believed would compete with the holism of the surrounding Paul Rudolph campus design—a cohort of brutalist buildings arranged around a campanile tower, on a quad landscaped with grassy mounds and spiraling paths and stairways.8 In making the revised proposal for the current site, Holt appears to have annotated Polaroid photographs with details of the campus traffic patterns, access points, and built environment surrounding the proposed work: “Site bounded by: stone wall/sidewalk/Ring Road.”9 She also took research photographs of the campus observatory visible from the Spinwinder location, and of textile machinery from SMU’s New Bedford textile studio, demonstrating her thinking about both the “astronomical locating” and “human experience” dimensions of place.

Early designs of the work contained a suspended pendulum form (indeed, the drawings for Spinwinder were housed in a portfolio titled “Spinwinder/Pendulum Drawings”), later replaced by the caged cylinder of the final form.10 These early renderings indicate what appears to be a void in the earth below an angular bell-shaped pendulum, and gears and pulley systems that might move the central object. Holt wrote on December 31, 1990: “The original blueprints . . . show two rotating wheels on two of the outer posts. For both aesthetic and safety reasons they have been omitted and replaced by spools of wound stainless-steel rope, which can turn slowly by hand.”11 Progressing into the form we see today, the designs shed their rotating wheels—perhaps references to those on machines like the knitting apparatus—and incorporated new interactive activities: pushing the central cylinder, turning the spools, and filling the circular central void with memorabilia and clay.

Willing visitors—using the full weight of their bodies, not mechanical gears—move the spools of Spinwinder. Recall the knitting machine comparison: here, instead of a tubular weave at its center, this machine has a core of bare earth, and a buried tribute to local industry and the artist’s grandfather. Based on recently-digitized photographic negatives at UMass Dartmouth’s library, the materials embedded in the foundation can be identified as fabric from a Southeastern Massachusetts University textile banner, parts of a spinneret machine, a shuttle for weaving from a power loom, various spools for a Jacquard loom and for holding cotton, and sock forms for knitting. Above this embedded box, topsoil was replaced by red clay to prevent growth of organic materials. Holt wrote in her proposal: “The earth in the center is rich, dense clay creating a circular earth mass with no organic growth (symbolic of planet Earth, Mother Earth). Artifacts of the textile industry are buried in the center of this area, creating a contained place of memory and reflection. The tubes . . . come together into a central cylinder, spraying out again like many threads forming a domed-shaped inner structure, which can be entered into and experienced from the inside.”12

The act of burying conjures other works by Holt, such as her Buried Poems (1969-71), along with other gestures of internment and embedding that memorialize or pay tribute to important people in Holt’s life. Where Spinwinder’s tribute to her grandfather is implicit, another Massachusetts campus sculpture has an explicit dedication to her mother. When invited to contribute to the journal Chelsea in 1981, Holt chose to publish the story of Wild Spot (1979–1980), a wrought iron circular structure in a wooded area on the Wellesley College campus, enclosing a core of native plantings. That story ends with the artist pulling off the road on a stormy birthday eve, in the Worcester County of her early childhood. There, she placed a phone call to Wellesley College “to dedicate Wild Spot to my mother, E. Louise Holt. The pieces of past and present mesh then, forming another of the coincidental webs that have repeatedly occurred in my life. Wild Spot has run full circle, it is complete.”13 Holt used similar language when discussing Spinwinder in a 1991 Boston Globe article, calling her artwork, and familial relationship to New Bedford, a “strange sort of circular journey.”14 Holt connected Spinwinder with Wild Spot in her interview with Lois Tarlow for Art New England in 1993, in which she called the center of Spinwinder a “sanctuary” and discussed central growth of indigenous wildflowers in Wild Spot as having “the quality of the inner being, the wild child nothing can touch—not education, not societal structuring.”15 These central spaces have inverse relationships to occupancy and life—one inlaid with non-fertile ground and meant to be explored, the other fenced off from human entry but full of vibrant flora. Both works commemorate Holt’s family lineage and personal ties to a region.

In 2021, Spinwinder was lightly conserved. As part of that effort, Spinwinder was joined by a new plaque that our campus team added in the spirit of Holt’s original proposal, and fresh red clay embedded in the central space. Yet Spinwinder shows its wear, as patches of moss have started to grow at its base. This change over time was appreciated by Holt in her creation of public art overall, as she reflected in 1993, in a roughly contemporaneous interview to the making of the sculpture, with Joyce Pomeroy Schwartz:

Pomeroy Schwartz: So you don’t mind if the works change—if plant material grows up on them?

Holt: No, I like that. And I like going back and seeing the works at different times of the year, and I like seeing them in the snow and the rain, and in the mist […] I’m concerned with that kind of natural time, or cyclical time, because it’s closer to what I’m really interested in, which is no time.16

Inviting us to turn its mechanisms and participate in its woven histories, Spinwinder moves in circles of recollection and return. Following many years spent with this sculpture in community, I feel the pulse of that cyclical time spanning the personal and public aspects of this work, bridging Holt’s family story and regional industrial heritage, bringing visitors to a space for both action and sanctuary, in one poignant, memory-infused, and continually activated place.

Selected Bibliography

Holt, Nancy, proposal for Spinwinder, “CVPA Art Gallery Director papers,” Claire T. Carney Library Archives and Special Collections, UMass Dartmouth, 1987–1991.

Lippard, Lucy R., The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, New York: New Press, 1997.

Massachusetts Cultural Council, “Massachusetts Art in Public Places Program: A Guide to the Art Collection” (July 1991).

Tarlow, Lois, “Nancy Holt” Art New England (June/July 1993), 40–41, 44.

Alena J. Williams (ed.), Nancy Holt: Sightlines, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

About the Author

Dr. Rebecca Uchill is Director and Professor of the Practice at the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture at University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC). In 2021-22, she organized Nancy Holt: Massachusetts, a program series and exhibition exploring Spinwinder (1991) on the UMass Dartmouth campus and Holt's relationship to the Southcoast region. She recently authored “In Stone Enclosures: Nancy Holt’s Extended Fields” for the Bruna Press volume Nancy Holt Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings (2022), edited by Kristina Lee Podesva.

- 1Massachusetts Cultural Council, “Massachusetts Art in Public Places Program: A Guide to the Art Collection” (July 1991), 6.

- 2John S. Hekman, “The Product Cycle and New England Textiles,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (June 1980): 709.

- 3Lucy R. Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: New Press, 1997), 270. (Lippard’s italics.)

- 4Lippard, Lure of the Local, 271.

- 5Lucy R. Lippard, “Tunnel Visions: Nancy Holt’s Art in the Public Eye,” in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. Alena J. Williams (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 60–61.

- 6Lucy Lippard, email interview by the author, January 6, 2022.

- 7Rebecca Uchill, Nancy Holt: Massachusetts, exh. brochure (College of Visual and Performing Arts, UMass Dartmouth, 2021); Rebecca Uchill, “Connecting the Threads: Nancy Holt’s Massachusetts,” presentation via Zoom for The Feminist Art Project, College Art Association, February 19, 2022, hosted by Rutgers University,. See also James Boaden, “Nancy Holt, ‘Underscan’ (1974),” part of Holt/Smithson Foundation’s Scholarly Text Program, February 2022.

- 8William Traubel, presentation for “Tour of Nancy Holt’s Spinwinder at UMass Dartmouth,” November 11, 2021 (video).

- 9Nancy Holt, annotations to photographs, June 1988, in Nancy Holt, proposal for Spinwinder, “CVPA Art Gallery Director papers,” Claire T. Carney Library Archives and Special Collections, UMass Dartmouth.

- 10Nancy Holt, “Spinwinder/Pendulum Drawings” portfolio, Holt/Smithson Foundation Collection.

- 11Nancy Holt, letter to William Traubel, December 31, 1990 (lightly edited for clarity), in Nancy Holt, proposal for Spinwinder, “CVPA Art Gallery Director papers,” Claire T. Carney Library Archives and Special Collections, UMass Dartmouth.

- 12Nancy Holt, proposal for Spinwinder, June 23, 1998. “CVPA Art Gallery Director papers,” Claire T. Carney Library Archives and Special Collections, UMass Dartmouth. Holt was clearly invested in evoking a form that would, in her words during adjustments to the proposal, “look more fluid, more like threads.” Nancy Holt, design rendering, “Variation–Final Version,” September 21, 1990, in Nancy Holt, proposal for Spinwinder, “CVPA Art Gallery Director papers,” Claire T. Carney Library Archives and Special Collections, UMass Dartmouth.

- 13Nancy Holt, “Wild Spot: Notes on a Few Coincidences of Art and Life,” Chelsea 39 (1981), republished in Williams, Nancy Holt: Sightlines, 107.

- 14Marty Carlock, “Brakes Squeal for New Art at UMass-Dartmouth,” Boston Sunday Globe, December 8, 1991, 82.

- 15Lois Tarlow, “Nancy Holt” Art New England, June/July 1993, 40, 41.

- 16Nancy Holt, oral history interview by Joyce Pomeroy Schwartz, August 3, 1993, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Uchill, Rebecca. "'Spinwinder' (1991)." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts (October 2023). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/spinwinder-1991.