Second Stage Injector

I have a dialectic between the center and the outer circumferences. [...]. It’s kind of interesting to bring the fringes into centrality and the centrality out to the fringes.1

–Robert Smithson

Robert Smithson is known for large scale land art pieces, in which center and periphery play an important role on the spatial level. He repeatedly quoted the French philosopher Blaise Pascal’s statement “Nature is an infinite sphere, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere” in his essays.2 His interest in “fringes” serves as a thematic continuum throughout his entire body of work, which also includes a series of collages and drawings created between 1963 and 1964. This series remained hidden from the public eye for a long time after Smithson's death in 1973.3 Smithson's widow, Nancy Holt, may have chosen not to make this series of works widely accessible, possibly due to numerous homoerotic references. It may have been the depictions of these and of the anthropomorphic in general that led Smithson to claim in 1972 that this series were created during a “kind of groping, investigating period” in which he was still undergoing his emergence as a conscious artist.4

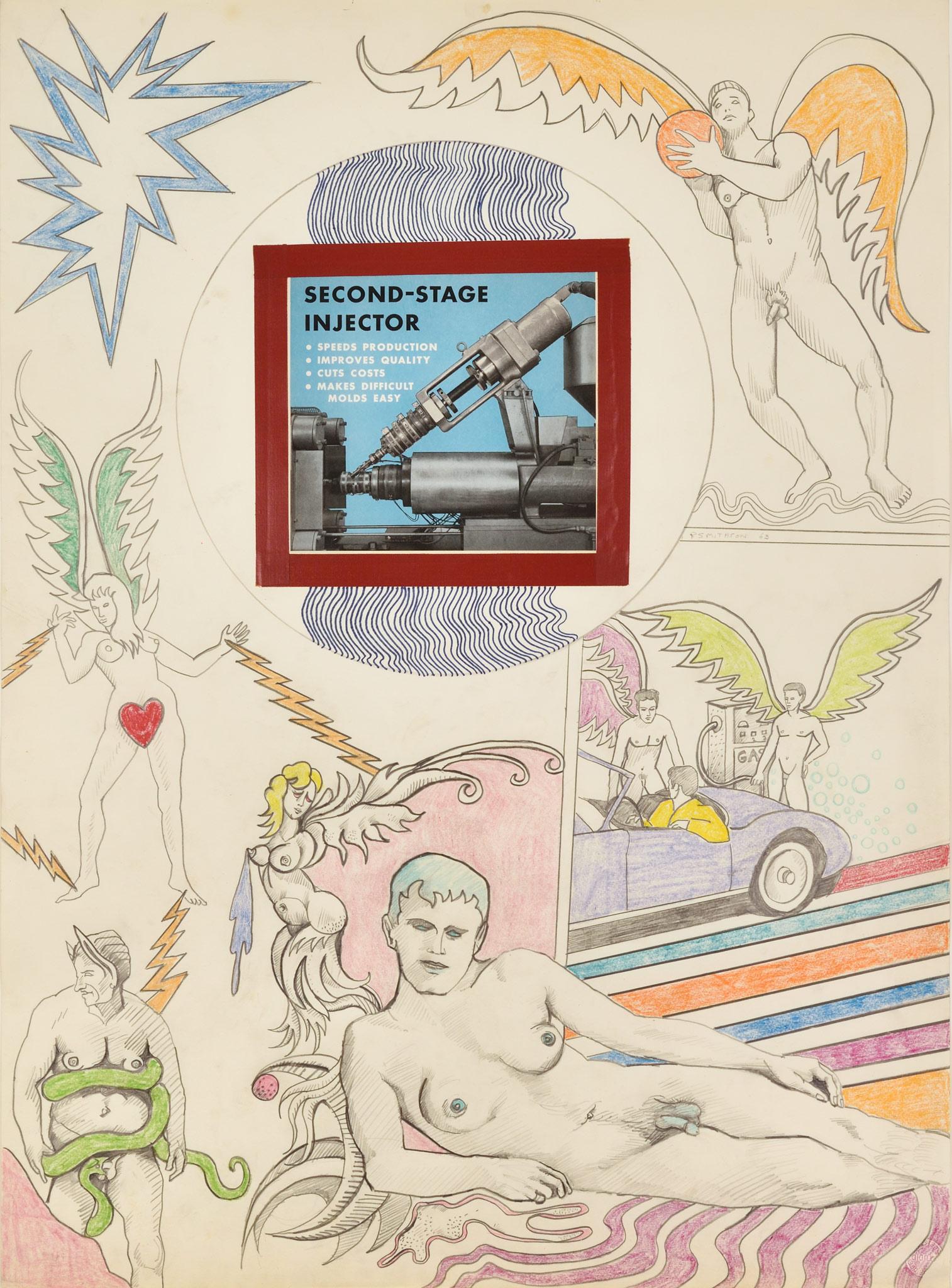

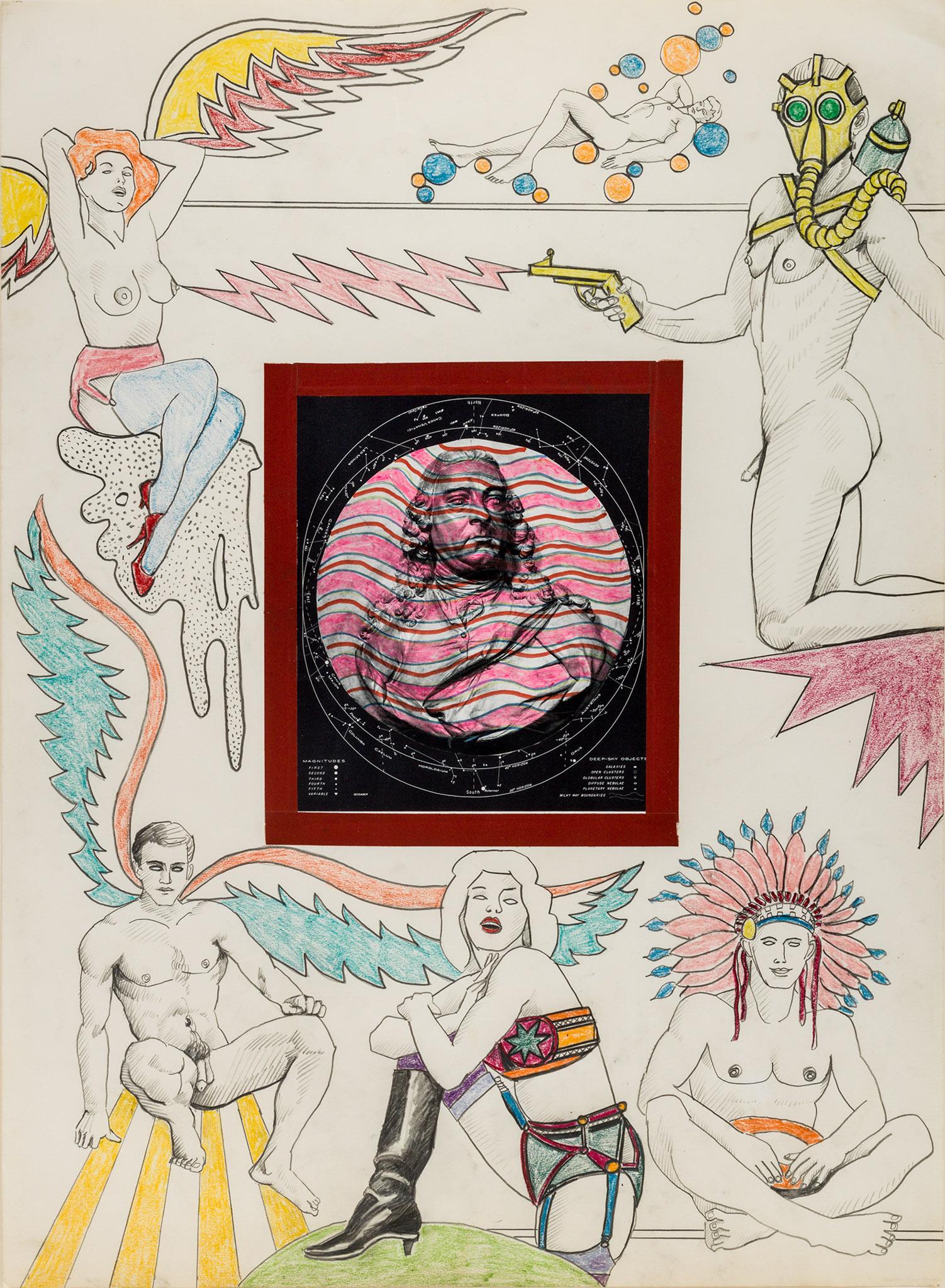

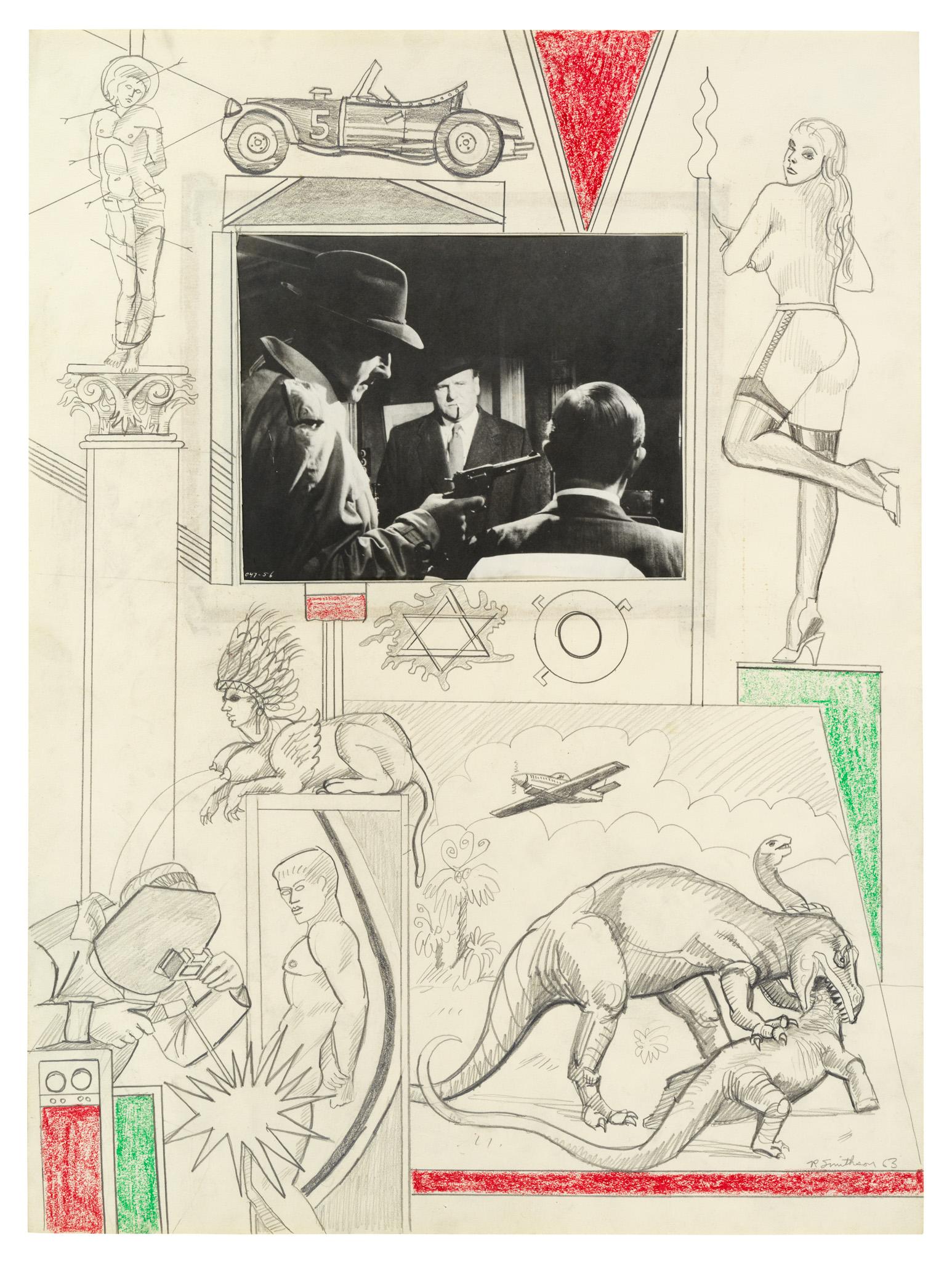

Indeed, this early series of collages might not be instantly associated with the artist. Untitled works, such as those from 1963 and 1964 illustrated at the top of the page, are characterized by Smithson’s playful approach to classical works of art history, such as Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (1536-41) as well as homoerotic imagery from beefcake magazines. Smithson titled only some of his early drawings, and they have often been referred to by descriptive names, such as Untitled (Second Stage Injector). Diverse and thoughtful, this early body of work not only reflects influences from pop art or mannerism, but also his engagement with mineralogy, entropy, and his fascination for dialectics.

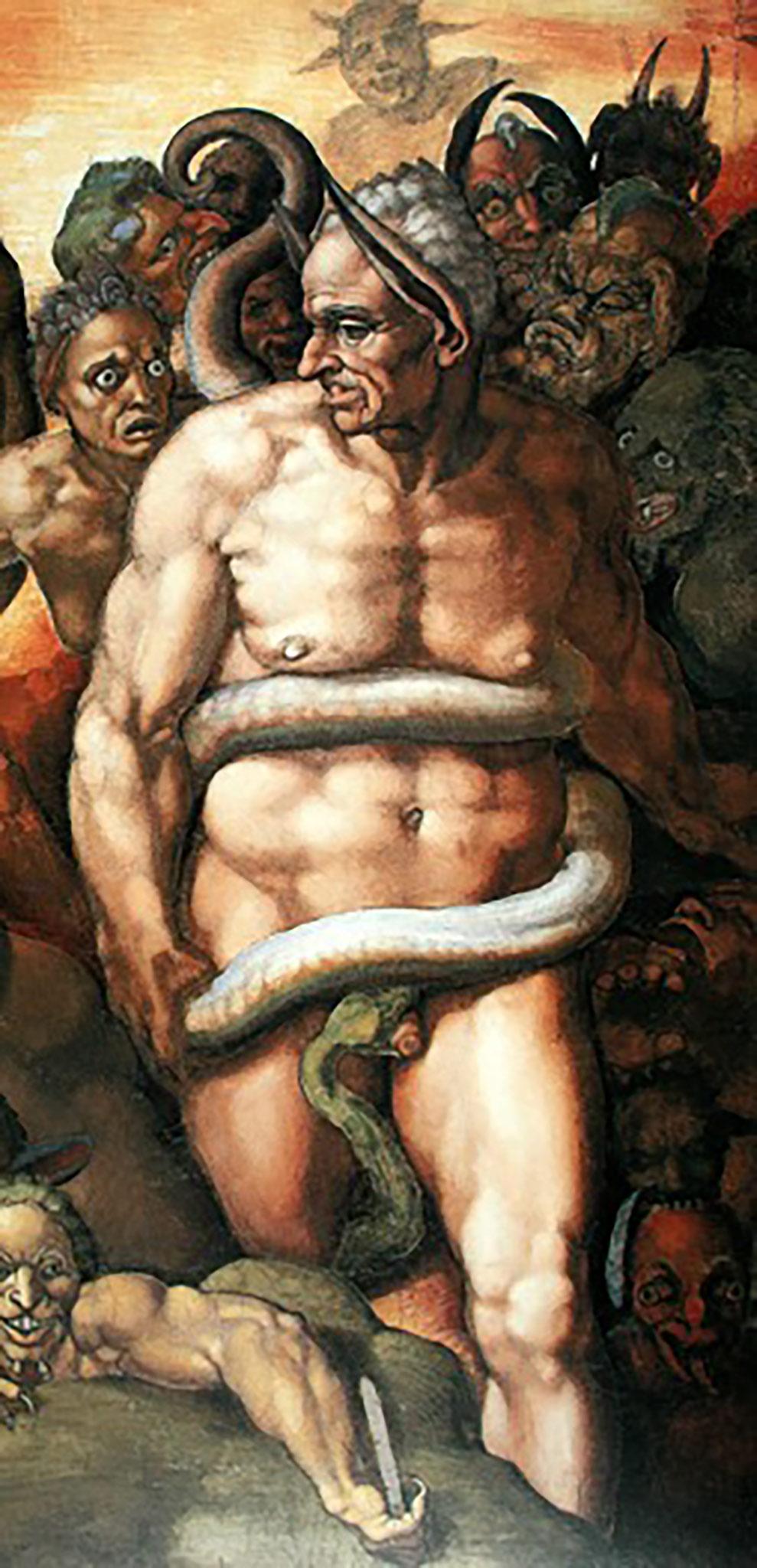

This thematic diversity is evident in the work known as Untitled (Second Stage Injector). Smithson arranges the events in his drawing in various sequences around an excerpt from an advertisement for a Second Stage Injector placed in the middle. From a reclining hermaphrodite with turquoise-colored female and male genitalia to a female figure, reminiscent of Italian grotesque painting, from whose breast liquid drips, to exposed female and male figures with jagged wings playing baseball or refueling their convertible, the viewer is presented with a comic-like scene filled with art historical references. In the collage, the representation of Minos from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel is also depicted, possibly influenced by Smithson's visit to Rome two years before the drawing’s creation.5 Smithson’s Minos is struck by lightning, emanating from the heel of a woman with wings, whose pubic area is a fiery red heart, hitting his right shoulder. The technical power of the Second Stage Injector seems to shift from the center to the periphery in the form of colored explosions.

In this body of work, Smithson reverses the traditional compositional hierarchy of centrally positioned figures surrounded by a subordinate frame by placing the narrative of his drawings from the center to the edge. In a 1972 interview, he described this series as “cartouches” that were “sort of proto-psychedelic”6 . According to this, Smithson highlights them as artworks characterized by the duality between a simple center and a richly decorated frame. All the drawings and collages feature a central geometric element surrounded by independently standing drawings within a frame which is vivid and moving. At least the composition of the cartouches seems to have been inspired by mannerism, particularly in the emphasis on framing. In his 1966 essay “Abstract Mannerism” he referred to the “great mannerism” as “[...] the ultra-consciousness of the ‘framing edge’ [...]”7 and quoted Jacques Bousquet from his book “Painting of Mannerism”: “By a typically Mannerist paradox, the frame became the picture.”8 9 The American philosopher Gary Shapiro sees another layer in this shift of Smithson’s human figures to the periphery: “[...] the figure here is parodied, pushed to the margins, and often transformed into a winged angelic or hermaphroditic figure. It is precisely the form (morphē) and centrality of the human figure (anthropos) which is put into question in this attempted liberation from anthropomorphism.”10

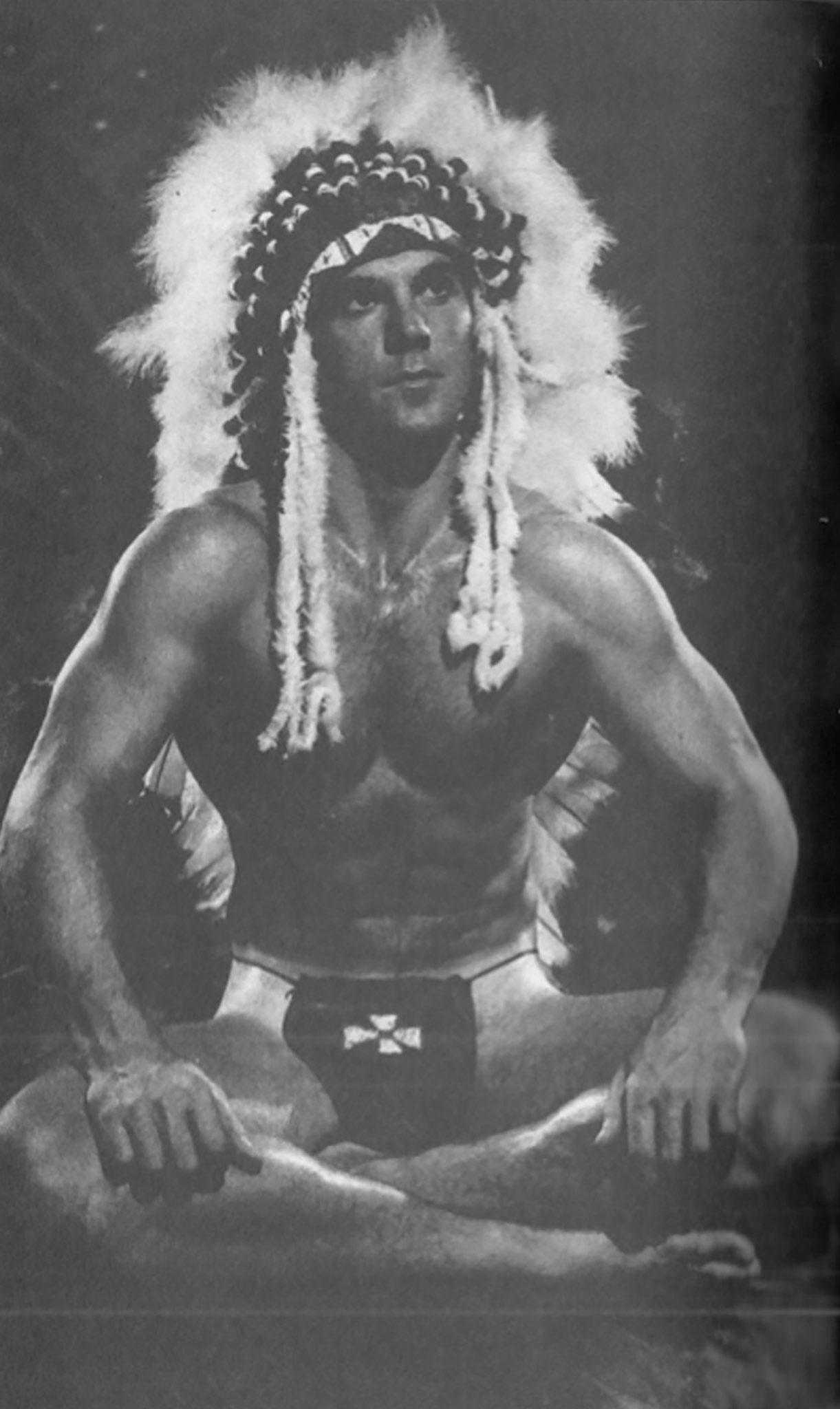

Smithson’s selection of central motifs was influenced by representations of the human body found in literature from the surrounding fields of art history, natural science, and science fiction. Inspiration for the often pornographic and homoerotic male depictions came from beefcake magazines such as Physique Pictorial founded in Los Angeles in 1945. The proportions and outlines suggest that Smithson actually may have traced some of the figures directly from these magazines. While the male athletes in Physique Pictorial photos were often depicted with loincloths, Smithson removed clothing from his cowboys, angels, or bikers. But he didn’t just leave them nude. He replaced clothes with accessories, such as a drum in the lap of the figure wearing a feathered headdress in the 1963 drawing. It’s not unlikely that the “athlete” sitting in a similar pose on the back cover of the August 1961 issue of VOL. XI No.1 served as the template for this drawing. Similarly, the depictions that Smithson borrowed from art history were primarily erotically connotated subjects, such as the portrayal of Saint Sebastian pierced with arrows in the 1963 drawing seen above.

It is precisely this content and compositional duality, combining classical works of art history with pornographic gay erotica, that makes these works relevant and timeless. Modern and classical, these are images in which Jesus becomes sexy and bikers divine, offering us a glimpse into the imagination of an artist who would become one of the defining figures of the 20th century. The works, which Smithson described as being from an “investigating period”11 are by no means “immature” works. Otherwise, the dialectic between center and periphery, as he later developed and oversized in his land art and Nonsites, would not be discernible even at this early stage. The cartouches can be read as media reflections that capture the conceptual creative richness of his later work, confined as two-dimensional media and framed by gay erotica.

Selected Bibliography

Jacques Bousquet, Malerei des Manierismus. Die Kunst Europas von 1520 bis 1620 (München, 1963)

Caroline A. Jones, “Preconscious/Posthumous Smithson: The Ambiguous Status of Art and Artist in the Postmodern Frame.” in: RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 41, 2002, pp. 16–37. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20167554.

Gary Shapiro, Earthwards. Robert Smithson and Art after Babel (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1995)

Robert Smithson, Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Jack Flam ed., (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996)

Eugenie Tsai, Robert Smithson Unearthed: Drawings, Collages, Writings, New York 1991.

About the Author

Teresa Hantke is Assistant to the Director of Hauser & Wirth Gallery in Paris. For the past two years, she has been the Senior Editorial Assistant at the German Center for Art History in Paris, where she supported various editorial and research projects. She completed her Master’s degree at the Sorbonne University, Paris and Humboldt University of Berlin, where she wrote about Robert Smithson’s early print work. For the past four years, she has been contemporary arts editor or the German online magazine gallerytalk.net and freelanced for magazines such as Monopol.

- 1Jack Flam, ed., Robert Smithson, The Collected Writings, “Oral history interview with Robert Smithson, 1972” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996, 300.

- 2Robert Smithson, “A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art” (1968); “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson” (1969-1970) in Flam 1996.

- 3Eugenie Tsai, Robert Smithson Unearthed: Drawings, Collages, Writings, New York 1991, p.24.

- 4Robert Smithson, quoted from “Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art / Smithsonian Institution / Paul Cummings” [1972], in J. Flam, ed.: Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Berkley 1996, pp.270–296, at p.283.

- 5As Caroline A. Jones argues, Smithson suggests in his essay “What Really Spoils Michelangelo's Sculpture” the origin of this figure, where the reference to "a snake chewing a penis" appears.

- 6Robert Smithson, quoted from “Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art / Smithsonian Institution / Paul Cummings” [1972], in J. Flam, ed.: Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Berkley 1996, pp.270–296, at p.289.

- 7Robert Smithson, “Abstract Mannerism,” in J. Flam, ed.: Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Berkley 1996, p. 339.

- 8Ibd., S. 339.

- 9Jacques Bousquet, Malerei des Manierismus. Die Kunst Europas von 1520 bis 1620, München 1963 (3. überarbeitete und aktualisierte Auflage 1985).

- 10Gary Shapiro, Earthwards. Robert Smithson and Art after Babel, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1995, p. 76.

- 11Robert Smithson, quoted from “Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art / Smithsonian Institution / Paul Cummings” [1972], in J. Flam, ed.: Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Berkley 1996, pp.270–296, at p.283.

Hantke, Teresa. "Second Stage Injector." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 6 (January 2024). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/second-stage-injector.