Robert Smithson’s "Texas Overflow" (1970)

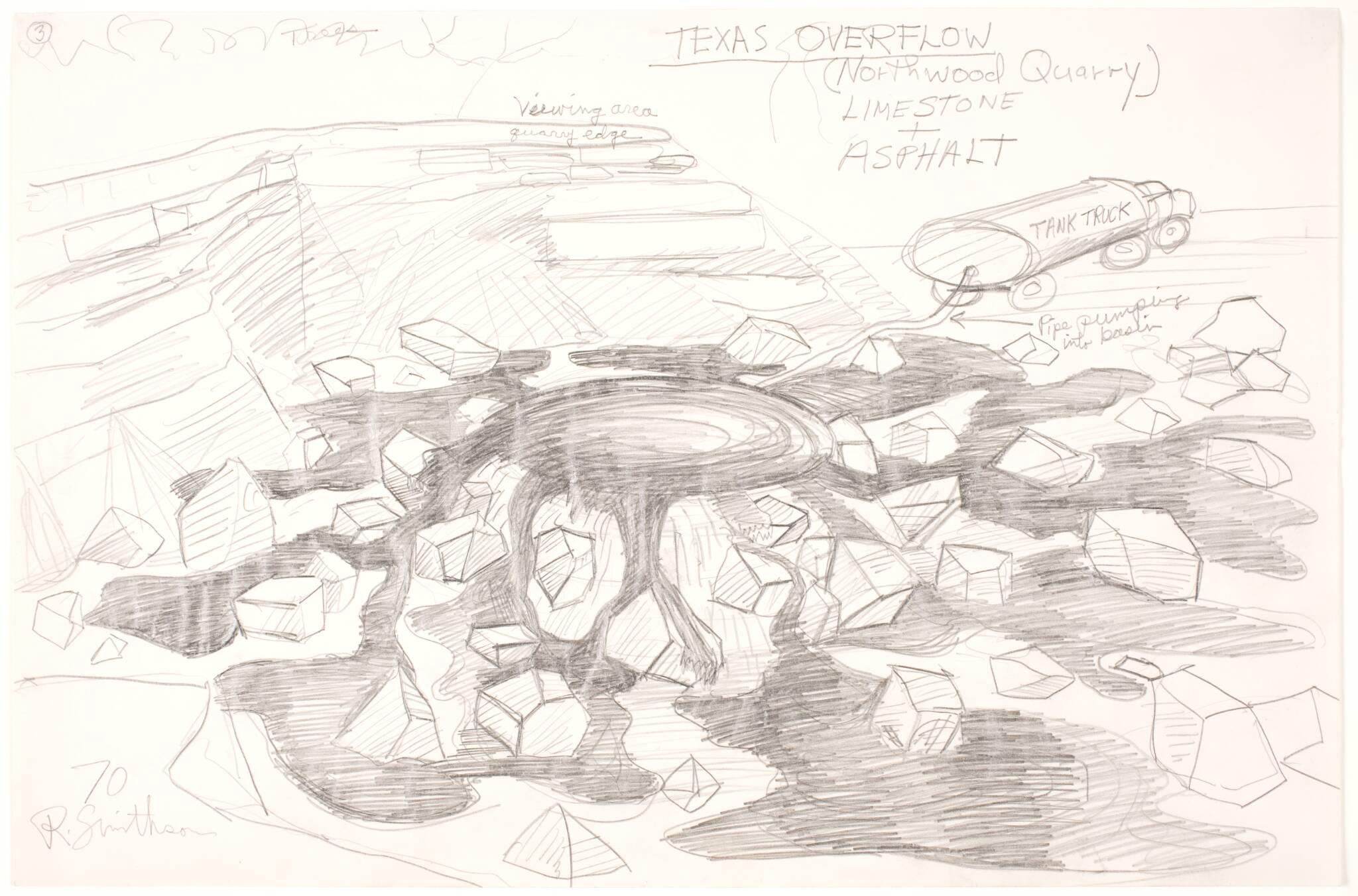

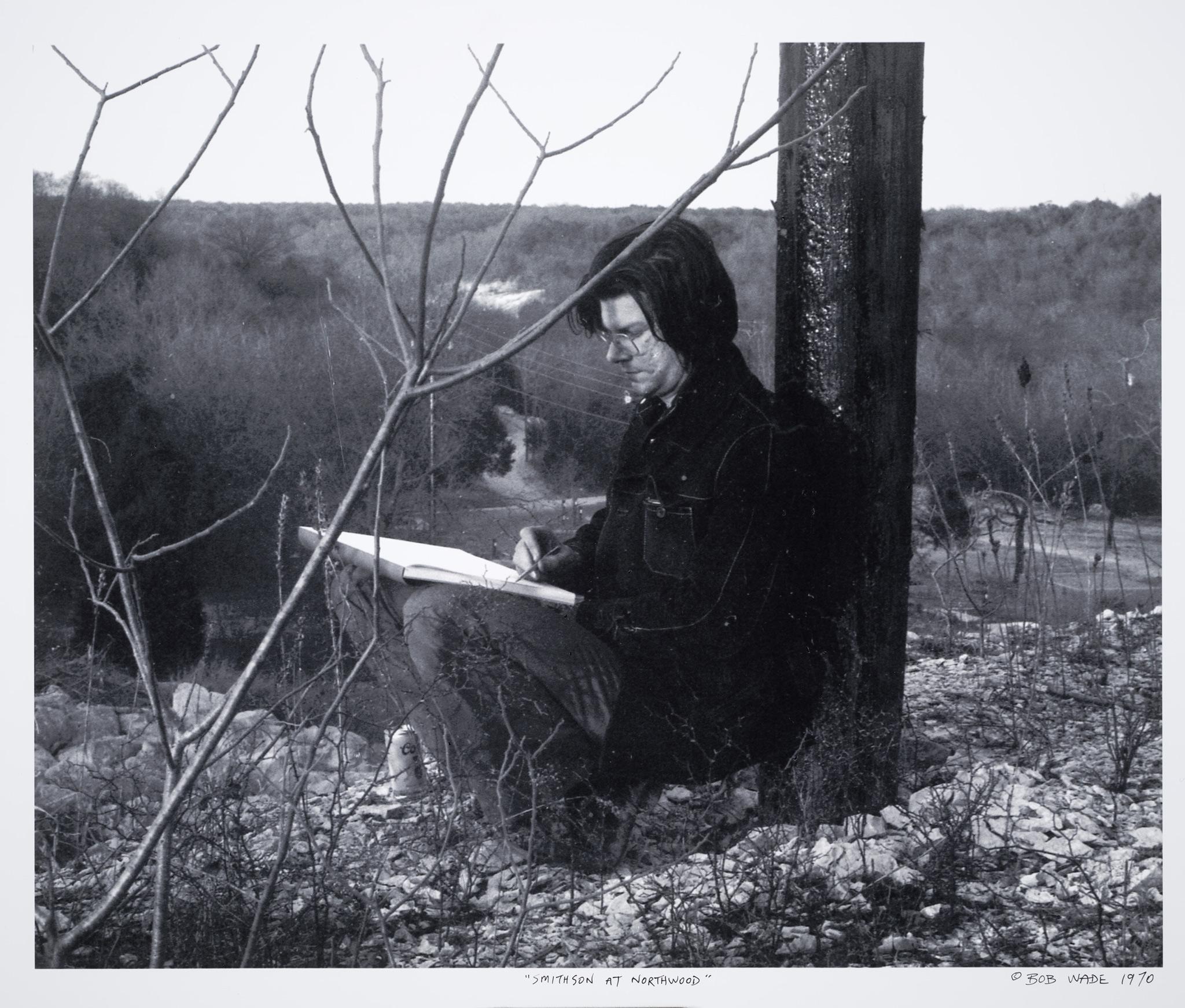

In early December 1970 Robert Smithson traveled to the Dallas-Fort Worth area at the invitation of the Northwood Institute—a private business college located just outside of Cedar Hill, Texas.1 The purpose of Smithson’s visit to this small suburb southwest of Dallas was to present his work to the students of the Institute’s short-lived Experimental Contemporary Art Program, while visiting area galleries and museums and meeting local arts patrons.2 At Northwood Smithson screened his recently completed film Spiral Jetty (1970) and gave a lecture to students of the program. He also toured the campus grounds where, among the uncharacteristically densely wooded area along the Balcones Escarpment, he discovered an abandoned quarry on the edges of the campus.3 Within a matter of days Smithson conceived an earthwork for the site that was to comprise hot asphalt pumped into the limestone quarry creating, what historian Robert Hobbs has described as, a “modern day tar pit, a monument to the tar pits of the prehistoric age." Smithson produced a maquette for the sculpture (temporary; no longer extant) and as many as twenty-six drawings.4 Several were film treatments, that included detailed instructions to document the preparation of the site and the construction of Texas Overflow. He was to spend the following year or more negotiating the project with the Fort Worth Art Center (now Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth).5

Smithson’s Texas quarry project aligns with such previous works as Partially Buried Woodshed (1970) and his “flows”—Asphalt Rundown (1969), Concrete Pour (1969), and Glue Pour (1969, realized 1970). In each of these works the artist collaborated with the natural forces of gravity to mimic geological processes that occur over millennia. With these “flows” Smithson explored how viscous materials could be used as stand-ins for dissipating energy, while historians have recognized their relationship to Abstract-Expressionist action painting.6

In Partially Buried Woodshed the collapsing of a shed is a metaphor for nature and its gradual dominance over the manmade, artificial space; in Asphalt Rundown, Concrete Pour, and Glue Pour the dumping of fluidic industrial materials down hillsides is a microcosm of large-scale landslides and environmental devastation, prompted increasingly by industry-related climate change. Smithson deployed the byproducts of industry—asphalt, glue, and cement—as material to make literal in situ landscape paintings that captured the contours of earth. But rather than focusing on the picturesque American landscape in the great tradition of Thomas Cole or Frederic Edwin Church, Smithson turned his attention to the fringes and backwaters, sites devastated by industrial pillaging:

My interest in the site was really a return to the origins of material, sort of a dematerialization of refined matter. Like if you took a tube of paint and followed that back to its original sources. My interest was in juxtaposing the refinement of, let’s say, painted steel, against the particles and rawness of matter itself.7

While in Düsseldorf in 1969 on the occasion of an exhibition at Konrad Fischer Gallery, Smithson toured the Ruhr-District, the largest industrial area in Germany, and here he recovered from the slag dumps a lump of solid tar that retained the impression of its former fluid state on its surface.8 Smithson installed the lump in Konrad Fischer Gallery directly on the floor as Asphalt Lump (1969), accompanying the found sculpture with a map of the area where it was recovered, thus transforming this industrial byproduct into a Nonsite. It was in this vein of attention to devastated landscapes and use of industrial waste that the artist conceived Texas Overflow for the abandoned limestone quarry at the Northwood Institute.

Hobbs’s characterization of Texas Overflow as a “monument to the tar pits of the prehistoric age” is particularly apt given the composition of its two dominant materials: limestone, a carbonate sedimentary rock often composed of skeletal fragments of prehistoric marine organisms (i.e., fossils); and asphalt, a petroleum-like material colloquially referred to as tar (e.g., the La Brea Tar Pits).9 Smithson’s idea for a tar pit sculpture can be traced back to his 1966 proposal Tar Pool and Gravel Pit, for which he intended to pour molten tar into a square bin situated within a larger square bin of coarse gravel. The artist wrote of the work’s ability to make “one conscious of the primal ooze” and described its transformation from kinetically active to inertly still: “The tar cools and flattens into a sticky level deposit. This carbonaceous sediment brings to mind the tertiary world of petroleum, asphalts, ozokerite, and bituminous agglomerations.”10 A similar effect would have been achieved with Texas Overflow. As the asphalt cooled, with its excess fanning out over the edges of the inner and outer limestone rings, the center pit would have leveled out to a black solid deposit, transforming the quarry into a time capsule containing the prehistoric inhabitants of the early Cretaceous period when an ancient shallow sea covered the area and dinosaurs still roamed the earth.11

Of the twenty-six drawings Smithson made for Texas Overflow, a suite of nine in The Royal Collection of Graphic Art, National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst or SMK) comprise the most detail about the project and further provide information about Smithson’s plans for a film to accompany the earthwork. These drawings are all signed and dated by the artist, as well as numbered in the top left-hand corner.12 When SMK accessioned the suite in 1998, the drawings were still affixed to a large sheet of cardboard, arranged in numerical order from top to bottom, left to right.13 In this format, the storyboarded drawings take on the appearance of a filmstrip, emphasizing Smithson’s intention to create an analogue to the earthwork via the medium of film. In addition fifteen drawings relating to the project are held in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA).14

In looking through the suite of nine drawings held in SMK’s collection, we can gain valuable insight into Smithson’s process for constructing the earthwork and documenting its creation. SMK drawing 2 demonstrates that making the sculpture would have required seven stages: these are described in the detailed film treatment depicting the development of Texas Overflow from an aerial perspective. Smithson’s focus on garbage removal in drawings 2 and 8 affirms his interest in reclaiming the former dump site as a location for an artwork. In the latter drawing he notes that the garbage could be incorporated into the earthwork, inscribing along the bottom edge of the sheet: “GARBAGE MAY BE BURIED UNDER ROCK & EARTH BASIN* OR REMOVED.” Drawing 8 details the first stages of the construction of the earthwork, while in drawing 3 of the SMK suite and this sketch from the MoMA group Smithson locates the primary spot on the edge of the quarry overlooking the earthwork’s ultimate transformation from a rock pile to a modern-day tar pit, suggesting he was thinking about how the work would be seen by viewers. In choosing a viewing location above the work Smithson was able to provide access to the bird’s eye view of Texas Overflow—a viewpoint previously only afforded viewers through the medium of film, as explicitly can be seen in Spiral Jetty. This aerial view Smithson would go on to achieve in physical space with the earthworks Broken Circle/Spiral Hill (1971) and the posthumously completed Amarillo Ramp (1973).

The group of drawings held in the drawing collection at MoMA are titled Sketch for a Quarry Project: Texas Overflow. These lack the detail of those found in the Texas Overflow SMK suite, and are generally looser sketches of the site and evolution of the earthwork’s construction. That the MoMA drawings are neither signed nor dated, further, suggests that this group comprises Smithson’s earliest ideas for the project—and there is evidence indicating they were each drawn in the same sketchbook Smithson is photographed with at the quarry.15 Further, the depiction of the quarry wall is unmistakably that of the Northwood Institute, and certain drawings here contain references to “Northwood” or the “Quarry Project”—notations that are likewise found in examples in the SMK suite. Considered together, the drawings in both collections reveal the development of Smithson’s conception of the work from rough sketches of ideas, to a formal proposal for an earthwork and film.

Today, the original location for the unrealized Texas Overflow is a storage shed housing such commercial groundskeeping equipment as riding lawnmowers, weed wackers, and other machinery, replacing what would have been a monument to the tar pits of the prehistoric age with a modern-day repository for machinery and technology that will soon be outmoded, if it is not already. Though unrealized, the Texas quarry project represents a crucial turning point in Smithson’s career when the artist was transitioning from a focus on works that connected interior and exterior spaces to becoming increasingly interested in the environmental concerns of mining reclamation and the recovery of industrially blighted landscapes—a pursuit that dominated the artist’s focus for the remainder of his life.16

Selected Bibliography

Flam, Jack, editor. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Hobbs, Robert C. Robert Smithson: Sculpture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981.

Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt papers, 1905-1987, bulk 1952-1987, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Smithson, Robert, Leigh A. Arnold, Amy von Lintel, and Jonathan Revett. Robert Smithson in Texas. New York: Estate of Robert Smithson and James Cohan Gallery, 2015.

Smithson, Robert, Brigitte Kalthoff, and Friedrich Meschede. Robert Smithson: Drawings from the Estate. Münster: Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, 1989.

About the Author

Leigh A. Arnold is a curator at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, Texas, where she curates temporary exhibitions and presentations of the permanent collection of modern and contemporary sculpture. Most recently, Arnold curated Elmgreen & Dragset: Sculptures, the first major US museum exhibition of work by the artist duo, and Sightings: Anne Le Troter, the French sound artist’s first exhibition in North America and her first work in the English language. Arnold is currently working on a historical reinterpretation of Land art that focuses on women who were involved in the movement. She received her doctoral degree from the University of Texas at Dallas in 2016, where she wrote on Robert Smithson’s unfinished projects in Texas.

With support from Henry Moore Foundation

Holt/Smithson Foundation's Scholarly Text Program has been funded in part through the generosity of the Henry Moore Foundation Grants Program.

- 1According to Smithson’s datebooks, the artist departed for Dallas, Texas on December 2, 1970; Nancy Holt met Smithson there December 5, 1970, and the couple returned to New York City on December 17, 1970. See: Microfilm roll 3832, slide 0560 in the Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt papers, 1905-1987, bulk 1952-1987, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- 2The Experimental Contemporary Art Program at the Northwood Institute was active 1968–1974. For more information about the college and art program, see: Leigh A. Arnold, “Texas as Nonsite: Robert Smithson’s Unfinished Works in the Lone Star State,” in Robert Smithson in Texas (New York: Estate of Robert Smithson and James Cohan Gallery, New York/Shanghai, 2013), 36–38.

- 3“The Balcones Escarpment, which runs through Cedar Hill, is one of the most defining physical characteristics of the area. Considered to be the highest point between the Red River and the Gulf Coast, Cedar Hill rises above 880 feet mean sea level. The Escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that formed as an effect of erosion or vertical movement along the Balcones Fault zone, giving its distinctive hillside character. While the Escarpment is prominent in Cedar Hill, this natural feature extends across Texas from the Red River to Del Rio.” “Escarpment Development,” Cedar Hill, accessed September 2, 2020, http://www.cedarhilltx.com/2584/Escarpment-Development.

- 4Twenty-four of the twenty-six drawings referenced in this essay are in public collections, with nine in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, National Gallery of Denmark and fifteen in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. It is possible there are more drawings related to Texas Overflow that are unknown to the author.

- 5Correspondence between Mary M. Haldeman of the Janie C. Lee Gallery, Dallas and Henry T. Hopkins, director of the Fort Worth Art Center, dated April 21, 1971 includes a draft solicitation letter to perspective funders that details Smithson’s 1970 visit to Northwood, his plans for Texas Overflow as a sculpture and a “film documentary to be released in galleries and museums in a limited edition,” and suggests $15,000 as needed to execute and complete the sculpture and film. See: “Northwood Institute” file in the Henry Hopkins Director’s Files, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. See also: John Coplans, “Robert Smithson, The Amarillo Ramp,” in Robert Smithson: Sculpture, ed. Robert Hobbs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981), 47-48.

- 6“In the first of these “flows,” Asphalt Rundown (1969), a dump truck released a load of asphalt from the top of an eroded hillside in an abandoned area of a dirt and gravel quarry in Rome. The effect, as seen in photographs, at first seems to resemble an enormous Abstract-Expressionist pouring of paint and appears to be a direct continuation of the large-scale heroic physical gestures associated with Jackson Pollock’s canvases. But at the same time that Smithson seems to be continuing the tradition of Abstract-Expressionist “action” painting, he also deconstructs that practice by emphasizing how the essentially entropic nature of the act of pouring differs from the individualistic gesture of painting. The implications of Smithson’s “flows” did not pass unnoticed. Recently, for example, Frank Stella remarked to me that Asphalt Rundown was perceived as a powerful, annihilating gesture that had forced all thoughtful artists to seriously reconsider the role of touch and surface in painting.” Jack Flam, “Preface,” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), xxii.

- 7Smithson in “Fragments of an Interview with P.A. [Patsy] Norvell (1969),” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), 192.

- 8Friedrich Meschede, “Asphalt Lump – Oberhausen Sterkrade 1969,” in Robert Smithson: Drawings from the Estate, Robert Smithson, Brigitte Kalthoff, and Friedrich Meschede (Münster: Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, 1989), 88.

- 9See: “A Guide to Rocks in Texas,” Nickelrock LLC, last modified June 22, 2015, https://nickelrockllc.com/texas-rock-guide/ and “Asphalt,” Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified December 27, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/science/asphalt-material.

- 10Robert Smithson, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects (1968),” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), 102.

- 11About an hour southwest of the Northwood campus is Dinosaur Valley State Park, where tracks of dinosaurs were discovered in the limestone bed of the Paluxy River in 1908. See: “State Opening 3 New Parks on Monday,” Dallas Morning News, May 31, 1970, 6.

- 12See: “Search the Collection: Texas Overflow,” SMK – Statens Museum for Kunst, accessed September 3, 2020, https://collection.smk.dk/#/en/q=texas%20overflow.

- 13Claes Kofoed Christensen, Curator at the National Gallery of Denmark, in conversation with the author September 17, 2014. For photographs of the drawings affixed to cardboard see: “Search the Collection: Texas Overflow,” SMK – Statens Museum for Kunst, accessed September 3, 2020, https://collection.smk.dk/#/en/detail/KKS1998-28, and Hobbs, Robert Smithson: Sculpture, 199.

- 14Nancy Holt gifted the museum eight drawings in 1987 and the Estate of Robert Smithson gifted the remaining seven in 1991. See: “The Collection: Sketch for a Quarry,” Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), accessed September 3, 2020, https://www.moma.org/collection/?utf8=%E2%9C%93&q=sketch+for+quarry&classifications=any&date_begin=Pre-1850&date_end=2020&with_images=1.

- 15The lack of dating on the MoMA group of drawings has led to inaccuracies in how the objects are described. Currently, the works are misdated to 1968.

- 16As Flam notes, “From 1971 to 1973, he [Smithson] wrote to and visited many strip-mining companies, making drawings and proposals for landscape works. He also wrote public statements that pointed out the limiting confines of the art establishment. The mining industry unfortunately was not very far-sighted, and rejected Smithson’s visionary proposals.” Flam, “Biographical Note,” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), xxviii.

Arnold, Leigh A. "Robert Smithson’s 'Texas Overflow' (1970)." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 2 (September 2020). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/robert-smithsons-texas-overflow-1970.