Lunar Imaginaries and Realities in Nancy Holt’s "Moon Book"

Nancy Holt had a persistent fascination with the Moon.1 In 1988, Holt shared that she hoped to create an earthwork dedicated to charting lunar cycles, and asked consulting astronomers: “What can I do with the moon that would be constant?” However, she learned that the Moon’s continual changes in position would make the kind of enduring monument she imagined impossible.2 Though Holt was never able to execute a site-specific work dedicated to the Moon, she made a small book-object titled Moon Book (1972), previously undiscussed in the scholarship. This project was made soon after Holt developed her Locators and predates her large-scale earthworks that refer to celestial phenomena, such as Sun Tunnels (1973-76) and Sky Mound (1986-). In Holt’s Moon Book the extraterrestrial imaginary of science fiction, from writers H.G. Wells and Frank Herbert, presses against the realities of scientific space exploration in the twentieth century.3 In 1969, the world watched as NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first people to walk on the Moon’s surface. The U.S. Apollo program would conduct six successful lunar landings between July 1969 through the end of 1972, building upon the legacy of the mediatized 1969 landing of Apollo 11. In Moon Book, Holt considers the Moon as a real location made more accessible through technological advances like these lunar missions, and the implications of that accessibility through examinations of the Moon as a site of cultural imagination, ripe for the mining of both symbolism and commodification. Moon Book offers insight into Holt’s capacity for incisive cultural critique of her contemporary moment through mixed-media collage, adding a different texture to her oeuvre.

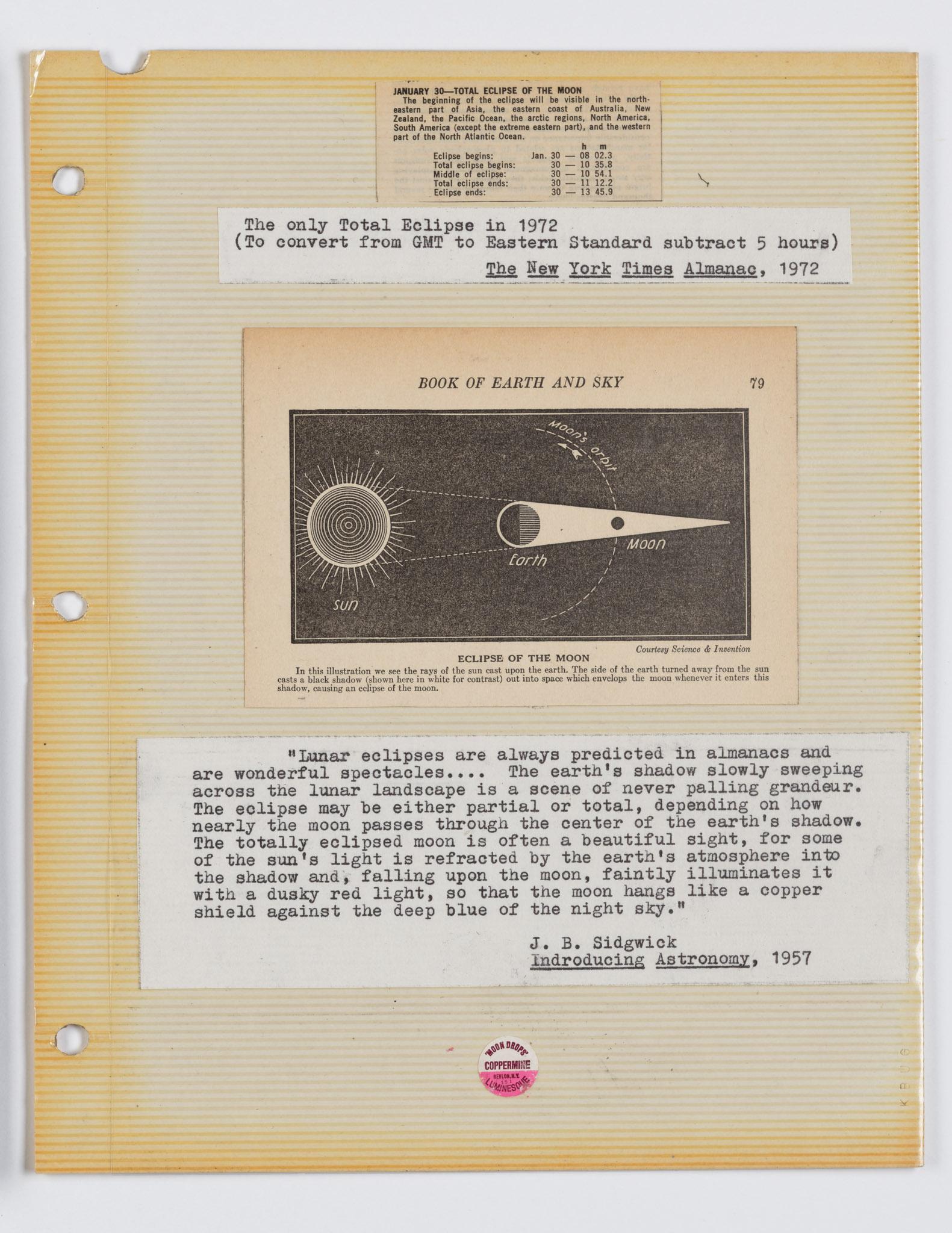

Moon Book consists of thirteen pages in the format of photo album, most of the pages collaged to combine text excerpts, prints, photographs, and ephemera, all related to the Moon. This intimate artwork is dated January 30, 1972, and is dedicated to the total lunar eclipse that occurred on that date.4 This Scholarly Text analyzes several pages of Moon Book, highlighting how Holt teases out issues of identity, extraction, and imperialism. At the bottom of page twelve, a small circular label anchors the composition (Fig. 1).5 The label is from the bottom of a tube of Revlon lipstick in the shade “CopperMine,” from the now-discontinued Moon Drops line. Above the lipstick label, a diagram from the Book of Earth and Sky illustrates a lunar eclipse. The label’s circular shape mirrors the diagram’s flattened representations of the Sun, Moon, and Earth, with the lipstick label as a potentially unknown planet in the solar system. An excerpt from J.B. Sidgwick’s Introducing Astronomy (1957) describes the visual spectacle of the phenomenon, noting that “…the moon hangs like a copper shield against the deep blue of the night sky.” The lipstick label’s shade name echoes this description of the Moon’s copper tone during a lunar eclipse, an evocative pigmented resonance between the scientific text and the cosmetic product.

Revlon’s “CopperMine” was released in 1970. With this lipstick, the techno-utopianism of the Moon landing was rapidly transformed into a mass-produced tool for self-adornment, targeted at women. Following the 1969 Moon landing, Revlon’s advertising strategy pursued a more futuristic, Pop-infused aesthetic, as seen in a 1970 advertisement for this lipstick (Fig. 2). For men, the Moon landing represented the century’s greatest technological advancement, a leap they could envision themselves taking. For women, the Moon could be harnessed through the purchase of a lipstick. During this time period, Holt was parsing out feminist issues in her artistic practice.6 In Making Waves, one of Holt’s concrete poems, she plots out three identities (feminist, artist, and mystic) as they diverge and intersect throughout a single day, February 2, 1972, just three days after the lunar eclipse noted in Moon Book. Looking back to 1972 from a position of five decades later in 2025, both Moon Book and Making Waves highlight Holt’s examinations of gender and feminism, as well as cultural structures of North American expansionism as they relate to society and individual identity.

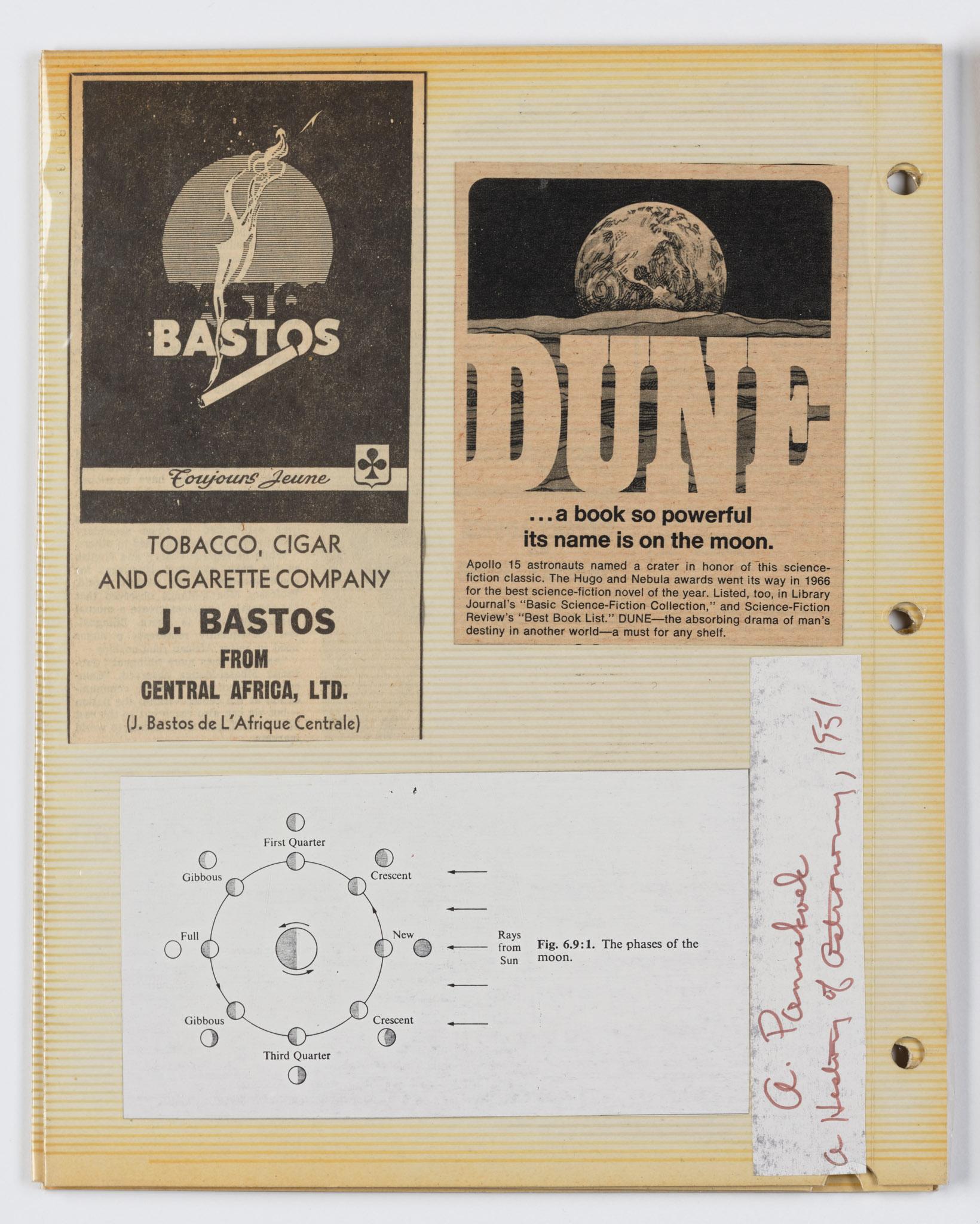

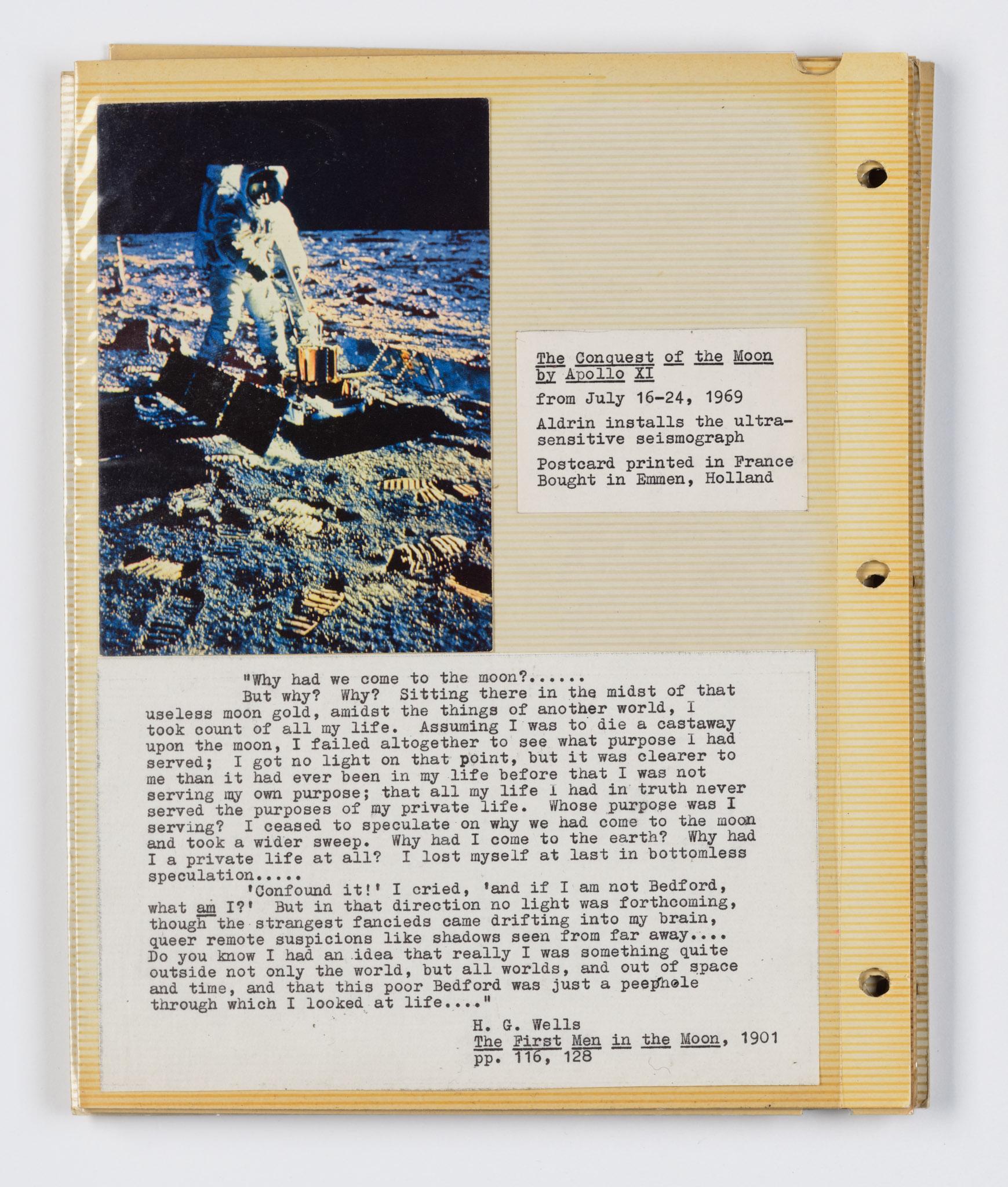

Holt’s selection of the Revlon shade “CopperMine” is doubly fitting, as Robert Smithson was in the midst of his Bingham Copper Mine land reclamation proposal while Holt made Moon Book.7 The lipstick label unites space age cultural imagination with the extraction of natural resources on earth. Though the Moon was not the site of any literal extraction, it did offer opportunities to symbolically mine, as demonstrated through Holt’s use of advertisements throughout Moon Book, from cigarettes and lipstick to the science fiction novel Dune (Fig. 3).8 Holt blurs the boundaries between knowledge and consumerism on page twelve, demonstrating the ease with which brands capitalize on the aesthetics of scientific advancements. On the following page, Holt includes an excerpt from H.G. Wells’ novel The First Men in the Moon (1901), which opens with the question: “Why had we come to the moon?” This excerpt reflects the moment in Wells’ story when the narrator Bedford, who initially sought to exploit the Moon’s natural resources, begins to question his motivations amid the “useless moon gold.”9 The narrator’s distance from Earth incites an unraveling of his sense of self and culturally-based value system. Holt’s choice of this passage highlights her critique of extractivism and how positionality can reshape identity, resisting a sense of fixity and echoing the lines of Making Waves, in which the individual’s characteristics wax and wane depending on the time of day.

Above the Wells excerpt, Holt includes a postcard of Buzz Aldrin on the lunar surface (Fig. 4). Next to Aldrin’s image is a caption that reads, “The Conquest of the Moon by Apollo XI.” It is unclear whether Holt penned this caption or typed out the text from the back of the postcard.10 The artist, who had previously worked as a copyeditor, wielded language with the utmost precision, so she chose the wording, whether or not it was her original phrase.11 With this textual choice of “conquest,” Holt invokes the history of colonization and U.S. imperialism on Earth as it extended into space. Apollo 11’s planting of an American flag into the Moon’s crust served the project of U.S. cultural imperialism under the optics of global advancement for mankind, ushering in a new era of the cultural mining operation on the Moon, where geopolitical realities now chafed against the imagined lunar landscape. The pairing of the Bastos tobacco and Dune advertisements on page six broadens Holt’s critique of imperialism beyond the United States. Apollo 15’s 1971 mission named one of the Moon’s craters after Frank Herbert’s Dune, a recent development that the publishing house capitalized on to boost sales of the 1965 novel. Both the advertising strategy and colonial act of naming a lunar crater miss the novel’s central critique of the exploitation of people and resources under an insatiable galactic empire. Amid Algeria’s fight for independence from French colonial rule following World War II, the Bastos Tobacco Company moved its operations from Algeria to locations in central Africa, noted in the advertisement Holt selected, mirroring the expansionist practices critiqued in Dune.12 Holt’s pairing of these advertisements highlights the Moon’s status in this period as a site of imaginative investment, demonstrative of the earthly lust for extraterrestrial resources and land.

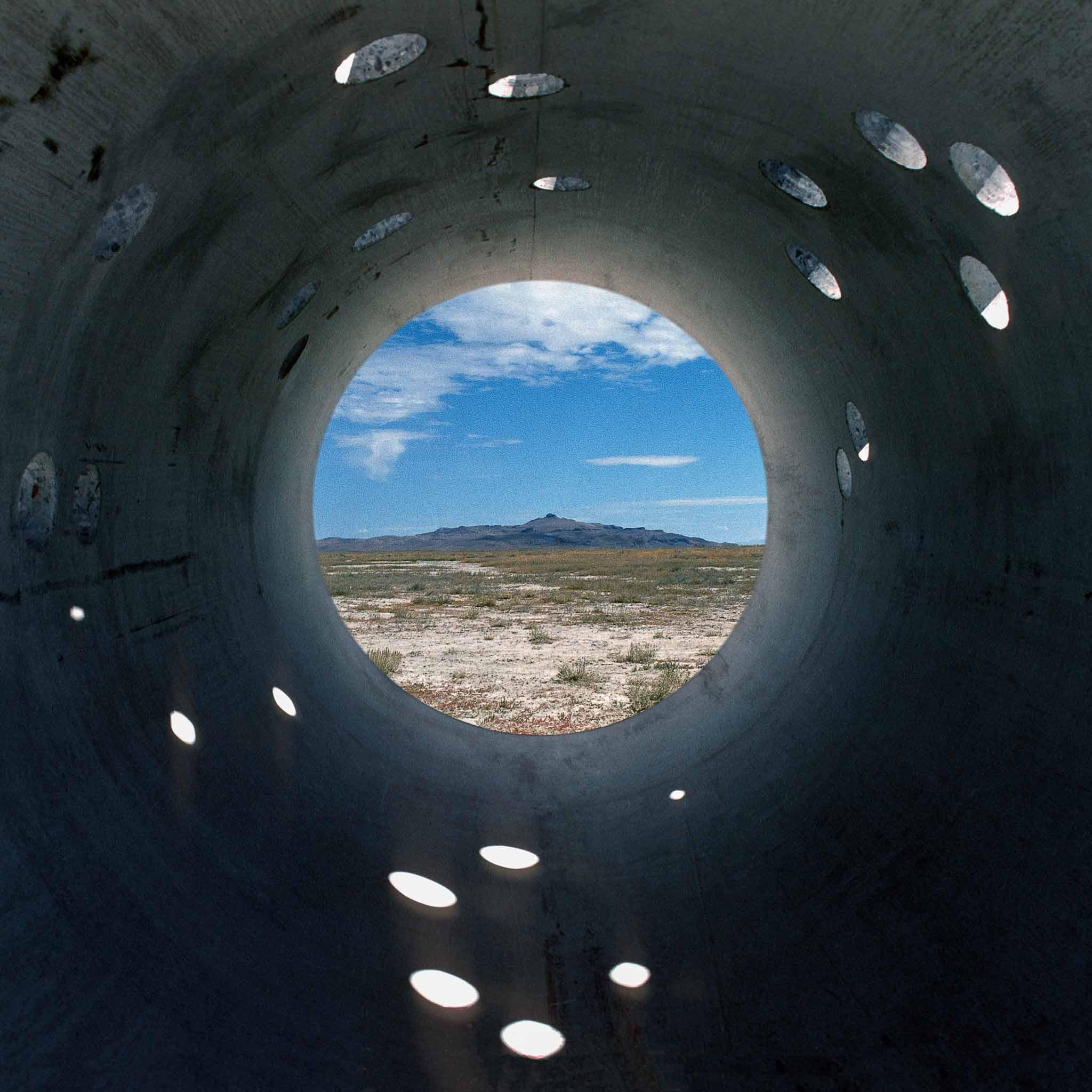

Holt said that her work was about “bringing the sky down to earth.”13 Though Moon Book is a small artwork, it teases out a number of central concerns in Holt’s practice and informs how the Moon might function in Holt’s site-specific work Sun Tunnels, begun in 1973. At night, the Sun’s light reflects off the Moon, perhaps shining through the constellation holes along the top of each tunnel and allowing nighttime visitors to walk on the Moon or some stars by walking upon their light projected along the tunnel floors, as Holt suggested (Fig. 5).14 Holt’s placement of Sun Tunnels in Utah ties into David Bourdon’s concept of the American West as a “lunar landscape,” with Holt echoing similar sentiments about her land being akin to the surface of the Moon.15 Holt’s sharp critique of U.S. imperialism softens from Moon Book into Sun Tunnels. Yet through the ephemerality of Sun Tunnels’ nighttime lunar projections, Holt subtly emphasizes the impossibility of human control of the universe. In our present moment, when billionaires launch themselves and celebrities into space in corporate-branded spacecrafts and discuss plans for colonizing Mars, Holt’s reminds us of the limitations of human dominion over nature, terrestrial and extraterrestrial. Through Moon Book and Sun Tunnels, Holt asserts the fullness of the Moon as a place of its own making, in contrast to the cultural constructions applied to its cratered surface.

About the Author

Brooke Eastman is a PhD candidate in Art History at Washington University in St. Louis. Her dissertation examines Land Art's relationships to legal and cultural conceptions of property in the U.S. and utilizes a land-centered approach to restore Indigenous land histories and epistemologies to the sites of these Earthworks. She holds a Harvey Fellowship in American Culture Studies and a Dean's Distinguished Graduate Fellowship. Brooke has held curatorial positions at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation and Leighton House Museum. She holds a BA in History of Art from Yale University and a MA in History of Art from The Courtauld Institute of Art.

Selected Bibliography

Holt, Nancy. “Sun Tunnels.” Artforum 15, no. 8 (April 1977): 32-37. https://www.artforum.com/print/197704/sun-tunnels-35992.

Le Feuvre, Lisa, and Katarina Pierre, eds. Nancy Holt / Inside Outside. New York: Monacelli, 2022.

Nisbet, James. Ecologies, Environments, and Energy Systems in Art of the 1960s and 1970s. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014.

Saad-Cook, Janet; Charles Ross, Nancy Holt, and James Turrell. “Touching the Sky: Artworks Using Natural Phenomena, Earth, Sky and Connections to Astronomy.” Leonardo 21, no. 2 (1988): 123-134. JSTOR.

Williams, Alena J., ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

With support from Henry Luce Foundation

This Scholarly Text is supported by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to further our public-facing research into the art and ideas of Nancy Holt.

- 1Alena J. Williams, “Introduction,” in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. by Alena J. Williams (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 31.

- 2 In this 1988 interview, Holt said, “I call up the astronomers and give them the latitude and the longitude, and I say, What do you think? What if you had an unobstructed horizon? What is the angle for the solstice? Then they figure that out. Or I ask, What can I do with the moon that would be constant? And they say, Well, the extreme positions are every 18.61 years. That kind of cyclical time is very interesting to me, although I am aware that even that changes.” See Janet Saad-Cook, Charles Ross, Nancy Holt, and James Turrell. "Touching the Sky: Artworks Using Natural Phenomena, Earth, Sky and Connections to Astronomy" Leonardo 21, no. 2 (1988): 128.

- 3There is a long literary history of imagined journeys to the Moon, dating back to antiquity. This genre picked up steam in the nineteenth century with the work of Edgar Allen Poe and Jules Verne, as well as H.G. Wells, and influenced early cinema, as in Georges Méliès’ film A Trip to the Moon (1902).

- 4In between the title and the date of Moon Book is a short dedication to the artist Carl Andre, with whom Holt frequently shared concrete poems, sent through the postal service. Holt made two concrete poems for Andre later in 1972 and 1973, engaging with celestial imagery and referring to Andre as “a guiding light, never waning or dimming in the arctic regions of the night.” Andre’s horizontal, floor-based sculptures offered viewers the opposite experience to gazing up at the Moon, as the girl in the title page’s illustration is doing, an image taken from the poetry volume Rhymes for Kindly Children (1916). For more information, see illustrations.

- 5While the pages of Moon Book are not numbered, Holt/Smithson Foundation has maintained the original order the artist kept in her studio.

- 6Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre, “Inside/Outside: Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre in conversation,” in Nancy Holt / Inside Outside, ed. by Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre (New York: Monacelli, 2022), 172-3.

- 7“Bingham Copper Mining Pit—Utah / Reclamation Project,” Holt/Smithson Foundation, accessed July 14, 2025, https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/bingham-copper-mining-pit-utah-reclamation-project.

- 8Holt’s interest in advertisements is also manifested in her photographic series California Sun Signs (1972). For more information, see https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/california-sun-signs.

- 9H.G. Wells, The First Men in the Moon, (London: George Newnes, 1901).

- 10As Holt notes in Moon Book, this postcard was acquired in Emmen, the Netherlands, the location of Smithson’s site-specific work Broken Circle/Spiral Hill (1971).

- 11“Nancy Holt Biography,” Holt/Smithson Foundation, accessed November 13, 2025, https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/biography-nancy-holt.

- 12Bastos opened factories in Dakar, Senegal and Cameroon following World War II and ceased all Algerian operations amid the Algerian War of Independence. Kingsly Awang Ollong, “Contentious Corporate Social Responsibility Practices by British American Tobacco in Cameroon,” Conjuntura Austral 8l, no. 41 (April/May 2017): 89. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/7441/744181010007.pdf.

- 13Holt interview with Saad-Cook, "Touching the Sky,” 123.

- 14Holt, interview with Saad-Cook, “Touching the Sky,” 127. The images of the constellation holes’ projections depict the work during the daytime, so envisioning the potentially softer, paler nighttime projections requires imagination.

- 15James Nisbet, Ecologies, Environments, and Energy Systems in Art of the 1960s and 1970s (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014), 93; and Holt, interview with James Meyer, in Nancy Holt: Sightlines, ed. by Alena J. Williams (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 231.

Eastman, Brooke. "Lunar Imaginaries and Realities in Nancy Holt’s Moon Book." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 9 (January 2026). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/lunar-imaginaries-and-realities-nancy-holts-moon-book-0.