Upside Down Trees: Terminal Transmissions

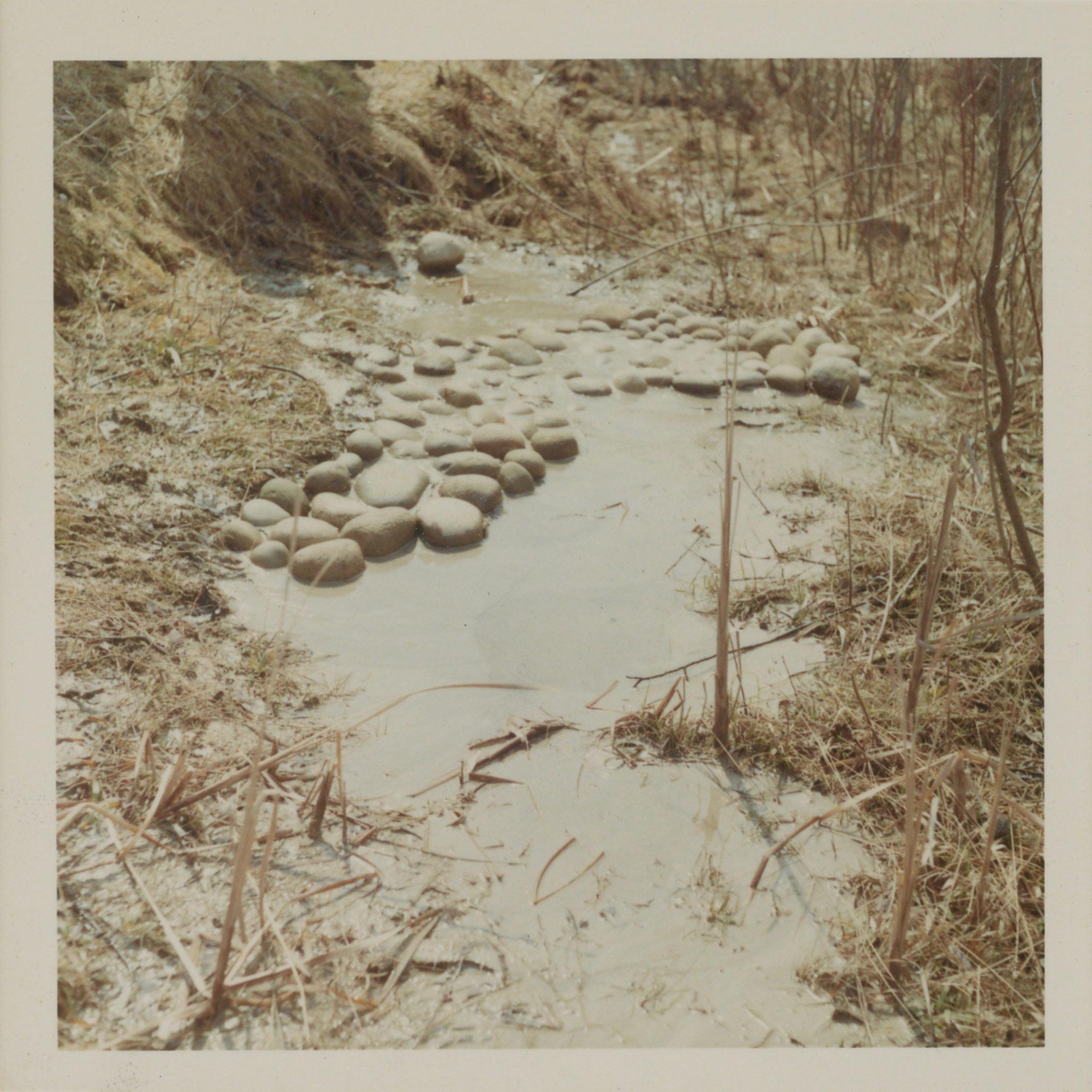

Robert Smithson’s Upside Down Trees (1969) form a circuit with the artist’s parallel series of earth maps, one that materializes and satirizes period visions of the growing informationalization of art and perception. The first Upside Down Tree was “planted,” its roots eerily reaching skyward, by students under Smithson’s guidance during his term as a visiting artist at the State University of New York at Alfred in April 1969.1 Another product of this time at Alfred was the ephemeral earth map Hypothetical Continent in Stone: Cathaysia (1969), which temporarily re-materialized the contours of the Late Paleozoic microcontinent as an appropriately entropic arrangement of stones deposited in quicksand.2 As recorded in his conversations with filmmaker Dennis Wheeler, the Hypothetical Continent in Alfred marked the first in a sequence of ephemeral earth maps that were projected to culminate in the artist’s unrealized proposal for the Island of Broken Glass to be sited on Miami Islet in the Strait of Georgia—a project thwarted by the protests of environmentalists.3

The second Hypothetical Continent, Hypothetical Continent in Shells: Lemuria (1969), was realized on the coast of Sanibel Island in Florida in conjunction with a second Upside Down Tree installed on the adjacent Captiva Island with the assistance of Robert Rauschenberg.4 The Sanibel Island earth map marked a fictive turn in this trajectory, bringing into visibility the theoretical continent of Lemuria, whose existence was disproved by the discovery of continental drift in the early twentieth century. Smithson executed these projects while visiting Rauschenberg during a stopover en route to the Yucatán Peninsula with Nancy Holt and gallerist Virginia Dwan in April 1969.

Smithson’s Yucatán travels with Holt and Dwan resulted in his era-defining photo-essay, “Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan,” published in the September 1969 issue of Artforum International. Meandering through an improbable network of references ranging from Aztec mythology to pseudo-scientific accounts of Atlantis, another fabulated island continent, the text documents Smithson’s temporary installation of nine Mirror Displacements at various sites on the trio’s Yucatán itinerary. At an archaeological site in Yaxchilan, the artist placed an array of nine mirrors in the branches of a tree. For Smithson, this installation conjured a monstrous version of the classical figure of the arbor inversa—“a giant vegetable squid inverted in the ground,” as he described it.5 It may have been this recognition that prompted the artist to install his third and final Upside Down Tree at the same site, which in turn elicited the artist’s most extensive and illuminating meditations on this series. Proposing that “lines drawn on a map will connect” the three Upside Down Trees, Smithson speculated that these works betoken a non-rational mode of travel.6 The artist’s likening of the Upside Down Trees to non-linear forms of transit connects this series back to the point of origin for his Nonsites and later earthworks; namely, his role as artist-consultant to the architectural and engineering firm of Tippetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton (TAMS) on its design proposals for the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport.

Smithson’s conceptualization of the Nonsite—an area peripheral to the gallery space that supplies data and raw materials for exhibition within its walls—was the “direct outcome” of his involvement with TAMS.7 Smithson’s proposals for monumental “aerial art” projects intended to be viewed by airplane passengers approaching or departing from the airport encouraged him to explore “information feedback” as a means of relaying these environmental artworks to the terminal interior, where they would be viewable on TV screens.8 Following the completion of his year-long contract with TAMS, and the non-materialization of his aerial art proposals, Smithson would return to, and reformulate, the notion of information transmission, initially through the Nonsites, which substituted two-dimensional documentation and physical samples for the televisual link envisaged for the aerial art projects.9 The subsequent Earthworks enabled Smithson to extend these explorations, beginning with a metaphorical mapping of Atlantis in glass at Loveladies, New Jersey.10 If Smithson’s installation of white limestone at Uxmal during his Yucatán travels reprised this Atlantean theme, Upside Down Tree III can be understood as a figurative reworking of the airport terminal as a locus of information transmission. Indeed, all three of Smithson’s Upside Down Trees exist in relation to earth maps in feedback loops that reprise the projected informatic relay linking airfield and terminal in the artist’s TAMS sketches.

Art-historical interpretation of Smithson’s Upside Down Trees as arbores inversa has tended to focus on longstanding deployments of this rhetorical figure to manifest “topsy-turvy” social conditions; in Smithson’s case, the multiple upheavals of the 1960s.11 A.B. Chambers has documented the alternate meanings attaching to the upside-down tree in classical tradition, including Plato’s schematization of the soul.12 In the Timaeus—a work cited by Smithson’s “Yucatan” essay that also discusses Atlantis—the philosopher likens the human body to “a plant whose roots are not in earth, but in the heavens.”13 The staunchly anti-idealist Smithson performs a characteristic reworking of this Platonic symbol, describing his upturned tree at Yaxchilan as a locus for flies: “Flies would come and go from all over,” he writes, “to look at the upside-down trees, and peer at them with their compound eyes.”14

The dispersed gaze of Smithson’s hypothetical insects aligns them with the anti-Gestalt valence of the “Yucatan” essay as a parodic rejoinder to the “optical” simultaneity and holism celebrated by the writings of reigning formalist critics Michael Fried and Clement Greenberg.15 Smithson’s invocation of a fragmented mode of visuality also identifies the flies as avatars of that eminently McLuhanesque technology of information transmission, television. Marshall McLuhan influentially described the TV screen as a pointillist field that might well invite analogies to the compound structure of a fly’s eye. Given their airborne comings and goings, the televisual associations of Smithson’s flies notably recall the aerial and remote modes of beholding envisaged for his Aerial Art proposals. In effect, the artist’s reworking of the Platonic figure of the inverted tree transforms the linear models of transmission upheld by formalist discussions of opticality into a dispersed field of information flow commensurate with the conditions of pervasive mediation in the 1960s described by McLuhan.

In a 1953 article for Shenandoah McLuhan invokes the Platonic soul to illuminate the perverse materialism informing the art and communication theories of his mentor, the British artist and author Wyndham Lewis—a persistent reference for Smithson as well.16 McLuhan observes that the dualistic oppositions structuring Lewis’s narratives and visual art—much like Smithson’s dialectic of Site/Nonsite—stage a satirical conflict between Plato’s aerial realm of ideal Forms and the terrestrial world of bodily appetite.17

Following Lewis’s example, McLuhan speculated that the growing ubiquity of media was transforming the planet into an interconnected “global village.”18 In his 1932 text Filibusters in Barbary, Lewis had invoked the “Sand-Wind” of the Sahara Desert described by French aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in Vol de Nuit (1931) as an ephemeral manifestation of Atlantis—Lewis’s favoured symbol for this planetary space.19 Surely Smithson, whose creative proposals for the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport remained such an enduring inspiration, would have found common cause with Lewis’s airborne Atlantis in his thinking about the earth maps.20 The arboreal lines of transmission linking Smithson’s Hypothetical Continents bring the information networks of McLuhan and Lewis’s planetary spaces into visibility. As Smithson declared, “the Earth is an island.”21

Selected Bibliography

Boettger, Suzaan. Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Chambers, A.B. “‘I Was But an Inverted Tree’: Notes Toward the History of an Idea.” Studies in the Renaissance 8 (1961): 291-99.

Flam, Jack, ed. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Reynolds, Ann. Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Ursprung, Philip. Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, and the Limits to Art. Translated by Fiona Elliott. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

About the Author

Adam Lauder graduated with a Ph.D. from the Department of History of Art at the University of Toronto. Lauder is the author of Out of School: Information Art and the Toronto School of Communication (2022), which includes a chapter on Robert Smithson’s Canadian connections, “Vancouver Vortex.” Lauder has also contributed articles to scholarly journals, including Afterimage, American Indian Quarterly, Canadian Journal of Communication, PUBLIC, and The Journal of Canadian Art History, as well as features and shorter texts to magazines including Border Crossings, Canadian Art, e-flux, esse, and Flash Art. In 2017-2019, Lauder was SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow at York University.

- 1See Suzaan Boettger, Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 221-22.

- 2See Robert Smithson quoted in P.A. Norvell, “Fragments of an Interview with P.A. [Patsy] Norvell [1969],” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 193.

- 3See Robert Smithson, “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson” [1969-1970], in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 200.

- 4See Virginia Dwan quoted in Sara Sinclair, “Excerpts from Interview with Virginia Dwan,” Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, 2014, https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/artist/oral-history/virginia-dwan; Holt/Smithson Foundation, “Smithson’s ‘Upside-down Trees’ at MoCA, Krakow,” April 19, 2019, https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/news/smithsons-upside-down-trees-moca-krakow; Ann Reynolds, Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 165.

- 5Robert Smithson, “Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan” [1969], in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 128.

- 6Ibid.

- 7Philip Ursprung, Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, and the Limits to Art, trans. Fiona Elliott (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 167.

- 8Robert Smithson quoted in Paul Toner, “Interview with Robert Smithson [1970],” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 234.

- 9Ursprung, Allan Kaprow, 167.

- 10Smithson, “Incidents of Mirror-Travel,” 133n1.

- 11Boettger, Earthworks, 223. See also Mark A. Cheetham, Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature Since the ’60s (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), 34.

- 12See A.B. Chambers, “‘I Was But an Inverted Tree’: Notes Toward the History of an Idea,” Studies in the Renaissance 8 (1961): 291-99.

- 13Plato quoted in Chambers, “‘I Was But,” 292.

- 14Smithson, “Incidents of Mirror-Travel,” 129. On Smithson’s anti-Idealism, see Boettger, Earthworks, 47.

- 15See Robert Linsley, “Mirror Travel in the Yucatan: Robert Smithson, Michael Fried, and the New Critical Drama,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 37 (2000): 7–30; Ann Reynolds, Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), Chapter 3.

- 16See Nico Israel, Spirals: The Whirled Image in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2015), 164; Gary Shapiro, Earthwards: Robert Smithson and Art after Babel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 29, 38; Eugenie Tsai, Robert Smithson Unearthed: Drawings, Collages, Writings (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 11.

- 17Marshall McLuhan, “Wyndham Lewis: His Theory of Art and Communication,” Shenandoah 4, nos. 2-3 (1953): 83.

- 18Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1962), 31. In America and Cosmic Man, Lewis proposed that “the earth has become one big village.” Wyndham Lewis, America and Cosmic Man (London: Nicholson and Watson, 1948), 16.

- 19Wyndham Lewis, Journey into Barbary: Morocco Writings and Drawings of Wyndham Lewis, ed. C.J. Fox (1932; repr., Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow, 1983), 173.

- 20Smithson’s library contains an anthology of writings by Lewis, including excerpts of Filibusters in Barbary. See Wyndham Lewis, A Soldier of Humor, and Selected Writings, ed. by Raymond Rosenthal (1932; repr., New York and Toronto: Signet, 1966).

- 21Smithson quoted in Paul Toner, “Interview with Robert Smithson,” 239.

Lauder, Adam. "Upside Down Trees: Terminal Transmissions." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 5 (October 2023). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/upside-down-trees-terminal-transmissions.