Everything and Nothing: On Nancy Holt’s "Sun Tunnels" (1973–76)

Let me tell you some things I like about Earthworks.1 I like that they are exposed. They are made and exist in the world and are subject to what the world does to them. Unlike artworks that dwell in archives or museum collections, they are not suspended from history; they persist in time. I like that they are unmarked. No signs posted, one finds them or doesn’t. I like their openness. There is not much to dictate my proper disposition toward them, except in the conditions that the site and the work allow. And I like that they are weak. Located within expansive and often extreme places, they are, by comparison, small, vulnerable, and crumbling. Photographs dramatize and mystify the works through skilled framing and isolation. In person, Earthworks are dwarfed by their environment, composed by absences, or made from mundane stuff. They are, in some fundamental sense, not even art-like, in the word’s earliest English meaning. There is little cunning to them or what they do.2

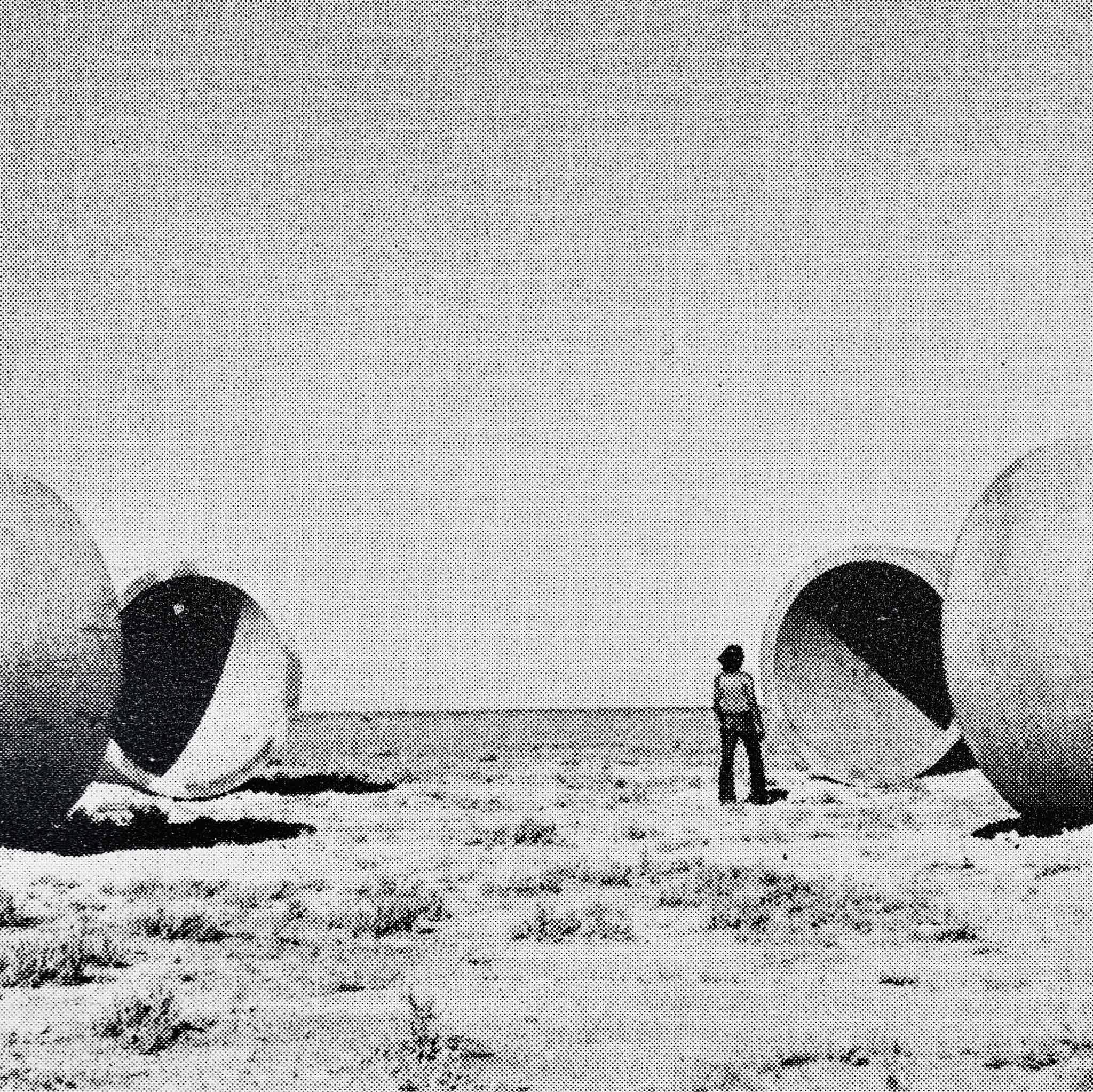

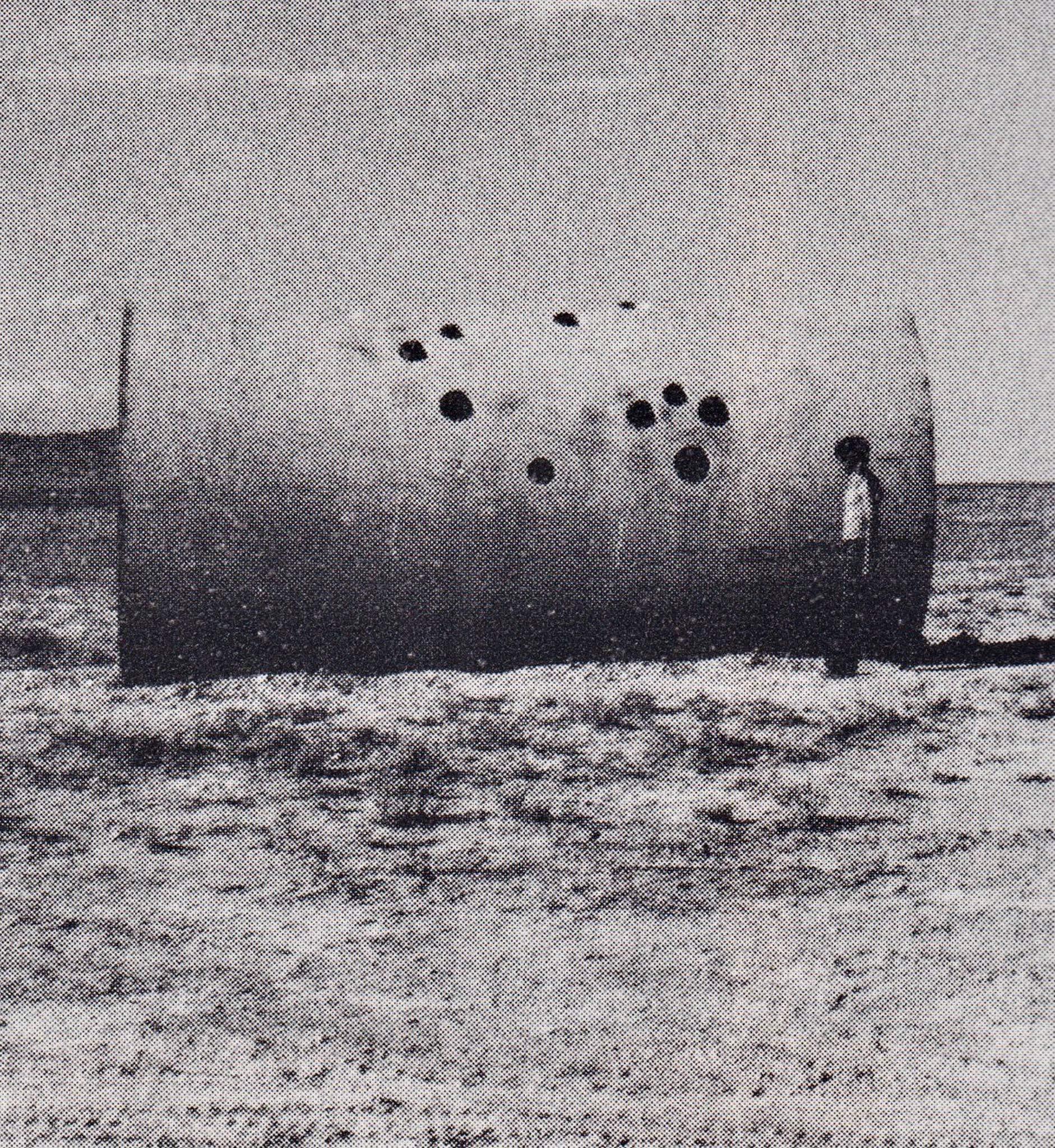

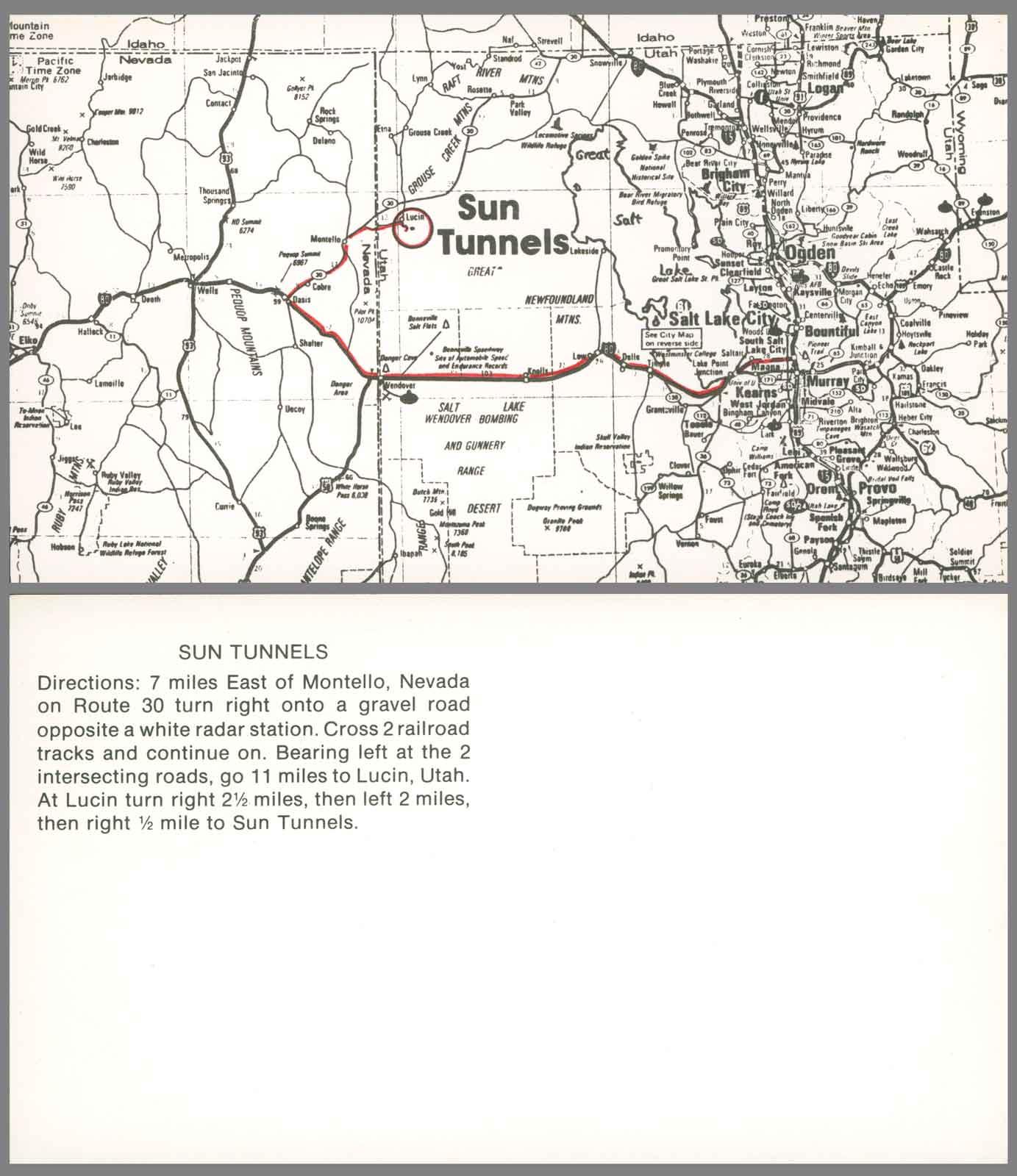

“You’ll be surprised at how nothing it is,” we are told by a resident of Montello, Nevada, the nearest settlement to Sun Tunnels, as we check into the Pilot Motel on our way to visit the work around the turn of the millennium.3 And early the next morning, when we follow the artist Nancy Holt’s faxed directions to her property across the state line in Utah, some thirty miles away, we find confirmation of the Nevadan’s appraisal. There is indeed something “nothing” about Sun Tunnels—a sense that is not dispelled by expectation or foreknowledge, by having planned, prepared, read, and traveled to see the work. Sun Tunnels engages an economy of means. Composed of four concrete pipes arranged on buried foundations in an open X formation, it is keyed to the extreme positions of the sun on the horizon at winter and summer solstices. To this simple arrangement, the artist added another element: holes bored into the sky-facing shell of each pipe in the shapes of the constellations Capricorn, Columba, Draco and Perseus.4

Located on land worn flat by the waters—long since dried up—of the ancient Lake Bonneville, the artwork has little inbuilt meaning. Unlike its sibling works—Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) or her partner Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970)—Sun Tunnels does not iconize the primordial. It appears instead as abandoned chunks of city infrastructure, massive drainpipes severed from urbanist purpose. Only incidentally sculptural, the artwork is primarily an instrument. And, like most tools, its form is structured by its intended use. On arrival, one uses the concrete pipes as sighting devices and spatial anchors in the vast bowl of scrub desert. Staring down the scope of the tunnels, one sees flattened, quasi-photographic views of the low ring of mountains that surround the lake basin. And, over time, a viewer begins to wander in orbits around the work—veering out before looping back as if under gravitational pull.

Sun Tunnels unfolded from a pair of realizations. The first came in 1968, when Holt flew with Heizer and Smithson into the Las Vegas airport. Stepping off the plane, she later explained, she had “an overwhelming experience of my inner landscape and the outer landscape being identical. It lasted for days. I couldn’t sleep.”5 A second realization proceeded from the first. Holt had begun, in the early 1970s, to make outdoor works, such as Missoula Ranch Locators: Vision Encompassed (1972), in Montana, or Views through a Sand Dune (1972), on Narragansett Beach in Rhode Island. Traveling with Smithson to Amarillo, Texas, to plot out Smithson’s earthwork Amarillo Ramp on the ranch of the millionaire Stanley Marsh 3, she found the oil tycoon was receptive to her building a work on his property.6 Holt had the idea of using concrete forms to construct a massive “locator”—her word for the sighting tubes that she had begun making and exhibiting in 1971—in the dry expanse of the Texas Panhandle.

The artist’s plan was forestalled by tragedy. While she was shopping in Amarillo for materials to build a model for her potential work, Smithson was surveying his earthwork’s site from the air in a light plane. The aircraft crashed, killing him, along with the pilot and photographer. After a period of mourning—which time included completing Amarillo Ramp, Smithson’s final work—Holt returned to her desert locator idea with new intensity.7 She began searching for a site in 1974, considering locations in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. “What I needed was flat desert ringed by low mountains,” she wrote, adding that it should be accessible by car.8 She finally found land in Box Elder County, Utah, near the vestiges of Lucin, a once-thriving railroad town.

After finding her site she spent weeks living in the isolated desert in her camper, feeling out the place, and meanwhile planning the work with collaborators whose expertise would allow it to function as intended: as a timepiece, aligned precisely to the sun’s rhythm. Doing so, she wrote, demanded that she become “more extended into the world” than she had ever been before.9 This self-extension licensed her sense of the work’s potent social and psychic function: “I wanted to bring the vast space of the desert back to human scale,” she explained.10 Human scale is indeed important to Sun Tunnels’ form. Holt resolved on a modest size for the pipes: big enough to walk inside, but not sizeable enough to intimidate or impress.11

Having said that, we should not overemphasize this aspect of the work. Sun Tunnels places its human viewers in contact with spaces and systems that are not at all human scaled, and that do dominate and overwhelm. Timekeeping and placemaking encounter the harsh, hallucinatory effects of sunlight in the Great Basin Desert. “When the sun beats down on the site,” Holt wrote, “the heat waves seem to make the earth dissolve, and the tunnels appear to lose their substance—they float like mirages in the distance.”12 Human existence is tentative in such a place—prone to unraveling under pressure of greater forces.13 What forces? Heat, distance, light, and the sun. The sun, Holt knew, is a star: the center of our existence, yet remote and indifferent to us. And the sun, she also argued, produces radical distortions in the mental frames we place on it. The desert is where this indifference and these distortions are laid most bare.

At Sun Tunnels, Holt writes, “the feeling of timelessness is overwhelming.”14 This adjective, overwhelming, is crucial, and links Sun Tunnels with her experience on the tarmac in Las Vegas, and with Amarillo, where the vastness of the horizon was characterized as “continuously overwhelming.”15 The repeated word conveys Holt’s attraction to the feeling it describes and her desire to negotiate that experience with her art. This sensation of openness and co-extension with space found recognition in the American desert and in her keen sense of humanity’s place on a rocky ball hurtling around a globe of flaming gases, in an expanding universe of trillions of such stars and orbs.16 The constellations on the concrete carapaces serve an aesthetic function, casting circles of light around the tunnels’ shaded interiors, but also remind us of human efforts to manage—to give form to—this otherwise unthinkable infinity. Sun Tunnels’ nothing, that is, opens onto everything. Holt stages the conditions wherein we may have the same sort of realizations, and thereby share in her arresting sense of serene overload.

Selected Bibliography

Holt, Nancy, “Sun Tunnels,” Artforum vol. XV no. 8 (April 1977): 32–37.

Holt, Nancy and Liza Béar. “Robert Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp,” Avalanche 8 (Summer/Fall 1973): 16–21.

Meyer, James, “Interview with Nancy Holt,” in Alena Williams, ed., Nancy Holt: Sightlines. University of California Press, 2011: 218–233.

Myers-Szupinska, Julian, “No-Places: Earthworks and Urbanism Circa 1970.” Dissertation. University of California, Berkeley, 2006.

Wagner, Anne M. “Being There: Art and the Politics of Place,” Artforum Vol. 43, No. 10 (Summer 2005): 264-269.

About the Author

Julian Myers-Szupinska is an art historian and editor based in Los Angeles. A scholar of contemporary art, exhibitions, and the politics of space, Myers-Szupinska was founding faculty in the Graduate Program in Curatorial Practice at California College of the Arts, the first program of its kind on the West Coast, from 2003 to 2020, and was senior editor of the Exhibitionist, a journal of exhibition making, from 2014 to 2017. Since 2011 Myers-Szupinska has worked with Joanna Szupinska in the critical collaboration grupa o.k. Their practices include editing, curating, criticism, and research, with a focus on the history and future of exhibition making and the forms and complexities of collective organization. Over the last decade, grupa o.k. has produced projects for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź, Poland, Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg, Canada, and other institutions. Myers-Szupinska’s edited volume of the writings by the curator and museum director Zdenka Badovinac, Comradeship: Art, Curating and Politics in Post-Socialist Europe, was published in 2019. Myers-Szupinska’s essays on contemporary artists and urban resistance include “Runaway Abstraction,” “Urban Fragments,” “After the Production of Space,” and an ongoing collaboration with the artist Edgar Arceneaux that manifested in the book Hopelessness Freezes Time, 2011.

- 1 I use the designation “Earthworks” advisedly. Holt referred to her work as “Land Art,” seeing the quasi-genre of Earth Art and Earthworks as belonging to an earlier group of male artists, despite them also being her contemporaries, peers, and fellow travelers. Yet there is something queasy and off-putting about “Land Art,” which conflates a reference to the surface of the planet not covered by water with other resonances: land as in country, land as possession and inheritance, land as in Woody Guthrie’s 1940 song “This Land is Your Land.”

- 2This paragraph’s brief description gives some indication of why I have little patience with the grandiose and macho formulations that are too frequently applied to these works—sometimes by the artists themselves. It also explains why my interest usually drains away when the same artists work in parks, plazas, traffic roundabouts, gardens, college campuses, museums, or large-scale exhibitions.

- 3 My first visit to Sun Tunnels was part of an Earthworks travel seminar at the University of California, Berkeley, organized by Professor Anne M. Wagner, visiting Double Negative and Spiral Jetty, as well as James Turrell’s Roden Crater—the latter under process of construction.

- 4 See Holt’s descriptions in “Sun Tunnels,” Artforum vol. XV no. 8 (April 1977): 32, 36–37.

- 5 James Meyer, “Interview with Nancy Holt,” in Alena Williams, ed. Nancy Holt: Sightlines. University of California Press, 2011: 222. Meyer asks Holt about the self and the landscape as part of an “inside/outside” binary. Holt replies, “Well, it’s interesting you say ‘the self,’ because the self is a construct, so it wasn’t really the self. It was me without a sense of self-identification. The landscape, the openness, was similar to the spaciousness I felt within. I was the land and sky and the land and sky was me… I was totally absorbed in my surroundings.”

- 6 Decades later, Marsh was indicted in Texas on 14 counts alleging coercive sex with underage boys. The case was quickly settled out of court. See “Stanley Marsh 3 settles teenagers’ lawsuits,” apnews.com (Feb. 16, 2013). Marsh died in 2014.

- 7 Amarillo Ramp was completed in August 1973 with a small team that included Richard Serra and Tony Shafrazi. Serra and Holt would produce two video artworks for KVII, an Amarillo television station and ABC affiliate owned by Marsh, including Boomerang and, in collaboration with the artist and musician Charlemagne Palestine, Match Match Their Courage, both 1974. Television Delivers People, a 1973 video by Serra and Carlotta Fay Schoolman, was also first broadcast on KVII.

- 8 “Sun Tunnels,” 34. “It was hard finding land which was both for sale and easy to get to by car.” Access by car was important for construction, but also for visitors. She wanted people to see the work.

- 9See also the discussion of Holt’s “self-extension” in Anne M. Wagner, “Being There: Art and the Politics of Place.” Artforum Vol. 43, No. 10 (Summer 2005): 264–269.

- 10 “Sun Tunnels,” 35.

- 11Compare Holt’s work to the fearsome sublimity of the Kennecott Copper Mine, west of Salt Lake City, or the solar evaporation ponds at Magcorp on the southern edge of the Great Salt Lake, or Utah’s many Superfund sites for radioactive waste disposal, or even just any urban highway, and find human-built structures of truly imposing, inhuman scale.

- 12 “Sun Tunnels,” 36.

- 13 In a recent conversation about Holt’s work, the video artist DeeDee Halleck, Holt’s close friend and a collaborator on the 1978 film of Sun Tunnels, recalled a frightening episode in which Holt suffered extreme heat exposure after visiting the work with Halleck and Richard Serra, requiring medical attention. See “On Nancy Holt’s Life and Art: A Conversation with DeeDee Halleck, Rachel Kushner, and Lisa Le Feuvre,” organized by The Contemporary Austin on April 5, 2021.

- 14 “Sun Tunnels,” 34.

- 15 Nancy Holt, “Robert Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp,” Avalanche 8 (Summer/Fall 1973): 16.

- 16 The number of stars in the observable universe can only be estimated, but it is in the order of many billions of trillions. And the “observable” part is a sticking point in any such estimation since it relies on current technology and human limitations. Some scientists suggest that there may well be an infinite number of stars. See also “Sun Tunnels,” 35. “Being part of that kind of landscape and walking on earth that has surely never been walked on before, evokes a sense of being on this planet, rotating in space, in universal time.”

Myers-Szupinska, Julian. "Everything and Nothing: On Nancy Holt’s 'Sun Tunnels' (1973–76)." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 3 (February 2022). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/everything-and-nothing-nancy-holts-sun-tunnels-1973-76.