Transient Materiality: Robert Smithson’s "Cayuga Salt Mine Project"

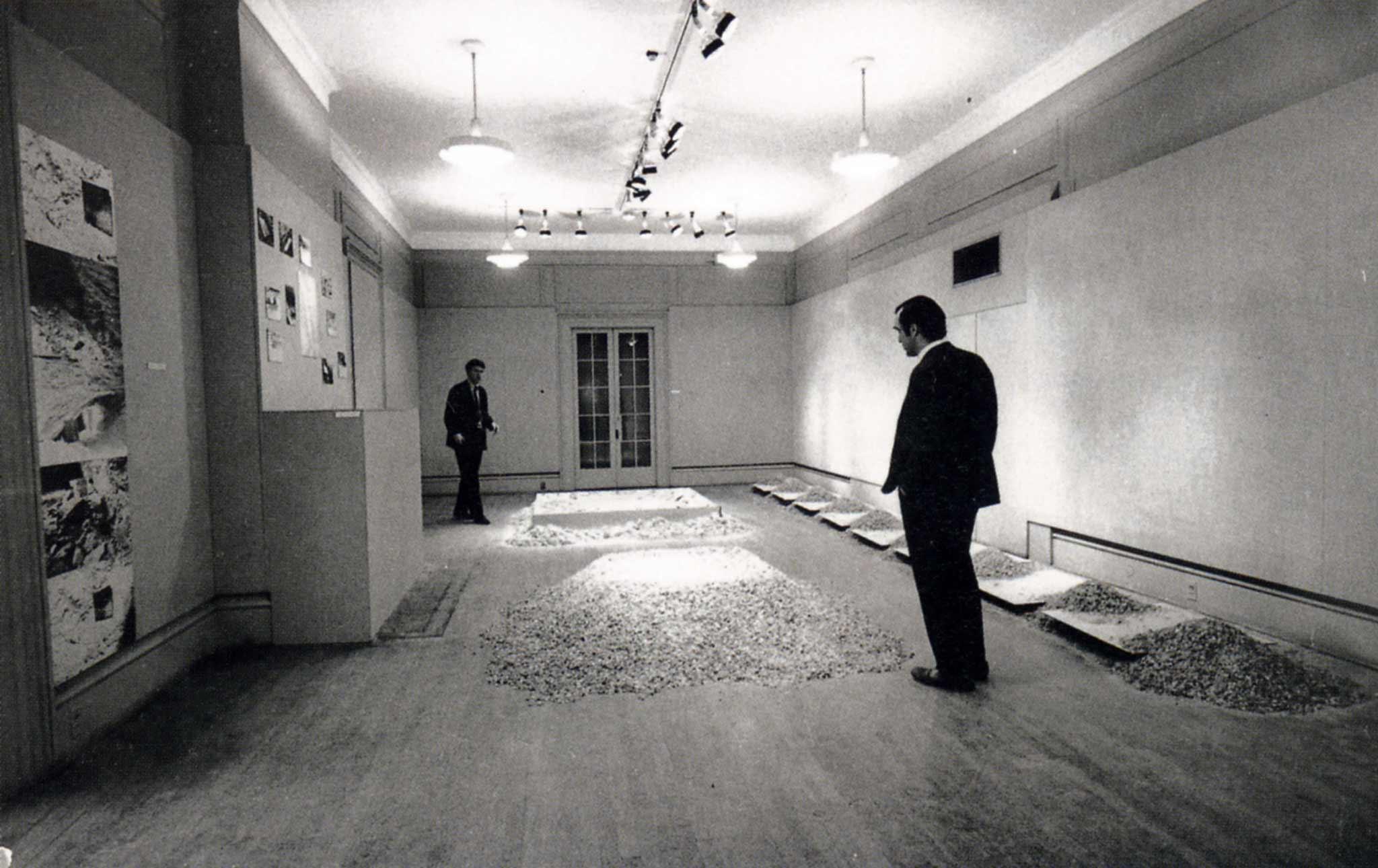

In February 1969, Robert Smithson created the Cayuga Salt Mine Project. The impetus for Smithson realizing the work was the landmark exhibition Earth Art at Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art in Ithaca, New York, and marks the only time it was shown in totality. The exhibition was one of the first to explore the so-called land art phenomenon, and brought together a significant roster of international vanguard artists to create works on-site, both in the galleries and across the environs of Cornell University.1 The Cayuga Salt Mine Project consisted of multiple components, all adapted to and made from local sites and materials. Though corresponding to Smithson’s other works and activities from the late 1960s, the project stands as something of a byzantine outlier within his practice. Perhaps owing to the incorporation of so many distinct elements comprising the project, critical analysis of the work has not been comprehensive and often misidentifies, segregates, or avoids aspects of the work. For Smithson, however, all of the components of the Cayuga Salt Mine Project constituted one total work united by the presence, and dialectically the absence, of the mirror.2

At the core of the Cayuga Salt Mine Project was one of the most complex manifestations of Smithson’s Site / Nonsite dialectic. This consistently involved the artist visiting a particular location, the site, and transporting some physical material from that place to an interior gallery space, the Nonsite.3 In this case the site was the Cayuga Salt Mine, located four miles north of Ithaca on the southeastern shore of Cayuga Lake, and the Nonsite was one of the galleries at the museum, which displayed maps, photographs of mirrors temporarily placed at the site, and five separate sculptures which all contained, in various forms, mirrors, and rock salt collected from the site and arranged on the floor.4 The work was bifurcated into two separate if mutually dependent parts. Cayuga Salt Mine Project was then complicated further by the demarcation and inclusion of a subsite / sub-Nonsite. This entailed additional mirrors placed above the mine in a nearby quarry and below the gallery in the museum’s basement.5 Cayuga Salt Mine Project is Smithson’s only work to include this element, as well as the first and only time he utilized subterranean sites.6

A mine was an especially apt space in which to explore and exploit the passage of time, especially one like the Cayuga Salt Mine that was still in use.7 With the slow extraction of salt the mine was in a constant, if imperceptible state of flux; it was a space embodying physical absence, where something once was, but is no longer. The reflections caught in Smithson’s mirrors, propped up by chunks of rock salt, and captured for posterity in photographs, show the remains and details of disintegrating surfaces that have been chipped, scraped, and cut away. As Smithson stated of the interior of the mine, “There you have an amorphous room situation…There are no right angles forming a rectilinear thing. So I'm adding the rectilinear focal point that sort of spills over into the fringes of the nondescript amorphousness.”8 Dimly lit, the mirrors enclosed and reflected a disorienting, fragmented, almost abstract space in what Smithson referred to as a “sort of rhythm between containment and scattering.”9

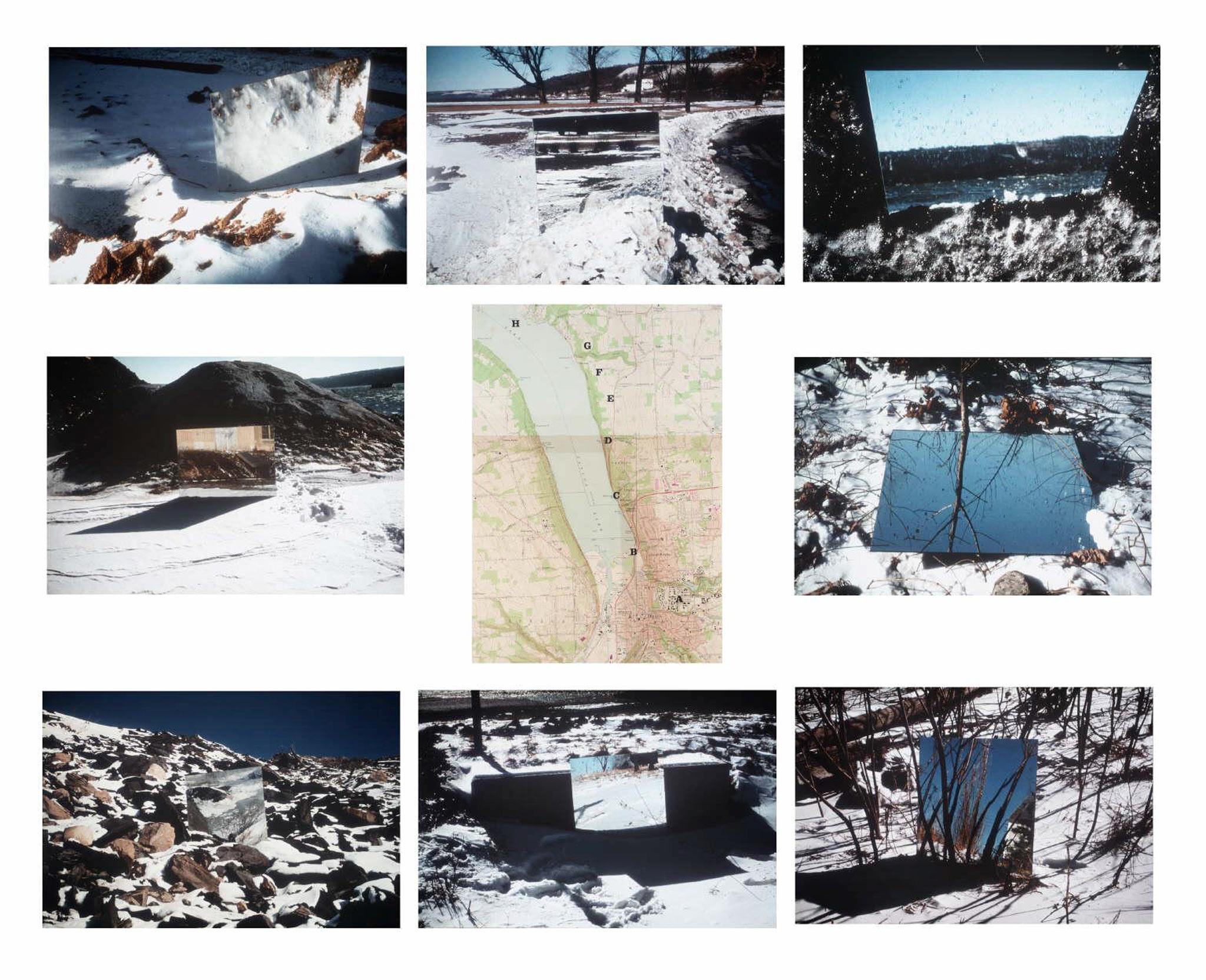

The Mirror Displacements in the mine were temporary, and related to a series of works Smithson created in 1968 and 1969 in which he set up mirrors in outdoor settings, photographed them, and then often reinstalled them in a gallery replicating their initial formations. The Mirror Displacements reflect a multitude of fleeting moments, while themselves they were physically ephemeral, being always dismantled and removed shortly after being photographed. The Mirror Displacements were predicated on the dislocation between the site, the object photographed, and the Nonsite where the elements were re-formed as sculpture In the case of the Cayuga Salt Mine Project Mirror Displacement, the additional creation of a Mirror Trail further emphasized the oscillation between presence and absence, as well as more explicitly connecting the site/subsite and Nonsite/sub-Nonsite.10 Unlike the Mirror Displacement, the Mirror Trail was an exercise in marking place and momentary reflections of presence. Beginning at the front of the A.D. White Museum, Smithson plotted eight points on a U.S. Geological Survey map and directly mimicked the interior Mirror Displacement using one of the same mirrors and photographing it at each point in succession from the museum to the mine. Subsequently marked A-H on a map that was displayed in the gallery Nonsite, these increments plot the distance between markers, as well as the time it would take to cover the distance, while the accompanying photographs mapped the transient time of the mirror’s presence at a particular location.11 For Smithson, the “route to the site was indeterminate” and a kind of oblivion, but Mirror Trail helped to bridge the abyss.12

Smithson did not simply enact this temporary placement of mirrors as a performance or to produce a staged photograph. As he stated, the resulting images served as “memory-traces” of vanished reflections, and remembrances of “vacant memories constellating the intangible terrains in deleted vicinities. It is the dimension of absence that remains to be found.”13 For Smithson, the photograph was yet another dialectic, both a physical material and a trace of an “on-the-spot experience.”14 Unlike the photograph, however, the mirror is not a trace of anything; its surface is unable to hold anything, and its reflections too fleeting. Thus, the photographs of the mirrors taken in the mine site or along the Mirror Trail do not depict the visible, singular, fixed image, but rather what is invisible. The images caught in the photographed mirrors grant access to what are but traces; one passing, suspended reflection caught in an arrested moment. Smithson’s tendency to create sculpture that, in its very form, is dispersed rather than permanent and whole, operated in the same manner. All of Cayuga Salt Mine Project's multiple parts manipulate and amplify the transient materiality intrinsic to so much of Smithson’s work. He did not seek to erase the existence of the object nor time. The physicality of the mirror is relentless, especially when arranged into sculptural form, and yet it constantly reflects away from its own presence. A sentiment that perhaps takes on another level of poignancy when one considers that today this work is a fragmented absence of absences.

Following the brief two-month run of Earth Art, all of the elements were dismantled, dispersed, reused, or put away. Never again exhibited together in its complete form, Cayuga Salt Mine Project has now become itself a displacement of mirrors, known only through photographs. The most comprehensive reinstallation was staged, again at Cornell, for the exhibition Robert Smithson: Sculpture in 1980. By then though, the museum had changed buildings and become the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art. A concerted attempt was made to faithfully reconstruct the various elements of the work, but the complete project and its particular locations were unavoidably altered.

The photographs, drawings, maps, and mirror pieces have been dispersed to and separately “reconstructed” in museum collections from Cleveland to Copenhagen. Regardless of their form, the mirrors of Cayuga Salt Mine Project continue to accost viewers with fleeting fragments of rock salt and physical space. They still present reflections that appear and disappear in rapid succession over the spatial void or “abyss” which has only grown larger with the passage of time. With its numerous, seemingly endless, fragmented parts, Cayuga Salt Mine Project can be understood as an overwhelming conglomeration of site/Nonsite, subsite/sub-Nonsite, Mirror Displacements, and Mirror Trails; collapsing under the weight of too many good ideas. By utilizing the material and conceptual possibilities of the mirror across these elements, however, Smithson physically manifested time’s intrinsic transience and its endless suspension. The complete artwork no longer exists, and yet the sheer physical presence of matter remains.

Selected Bibliography

“Discussions with Heizer, Oppenheim, Smithson,” Avalanche, no. 1 (Fall 1970): 48-71.

Earth Art. Ithaca: Office of University Publications, Cornell University, 1970.

Hobbs, Robert C. Robert Smithson: Sculpture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981.

Junker, Howard. “Down to Earth,” Newsweek, March 24, 1969.

Kozloff, Max. “Review of Earth Art,” The Nation, March 17, 1969.

Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson: Slideworks. Edited by Guglielmo Bargellesi-Severi. Verona: Carlo Frua, 1997.

About the Author

Marin R. Sullivan (PhD, University of Michigan) is a Chicago-based art historian and curator. She is the Director of the Harry Bertoia Catalogue Raisonné, and is co-curator of Harry Bertoia: Sculpting Mid-Century Modern Life, organized by the Nasher Sculpture Center. She also is Curator of Modern and Contemporary Sculpture at Cheekwood in Nashville. Sullivan is the author of Sculptural Materiality in the Age of Conceptualism (2017), as well as numerous essays and articles in publications including American Art, Art History, History of Photography, the Journal of Curatorial Studies, and Sculpture Journal.

- 1Earth Art was organized by Willoughby Sharp, an independent curator and publisher, with the assistance of Thomas W. Leavitt (1930-2010, then director of the A.D. White Museum of Art), William C. Lipke, (then professor of art history at Cornell University, who worked to photograph the exhibition), and Marilyn Rivchin, (the assistant director of the museum who was also in charge of all the filming of the project). Participating artists were: Jan Dibbets, Hans Haacke, Günther Uecker, Richard Long, David Medalla, Neil Jenny, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim, and Smithson. Michael Heizer and Walter de Maria both briefly exhibited their work, but were not mentioned in the catalogue, which was published the following year. Carl Andre had also been invited, but declined to participate. Earth Art Exhibition Archives, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. See also, Earth Art (Ithaca: Office of University Publications, Cornell University, 1970).

- 2Robert C. Hobbs, Robert Smithson: Sculpture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981), 132.

- 3In 1969, Smithson wrote a document outlining his Site/Nonsite dialectic, which was published in the catalog for Land Art, an exhibition curated by Gerry Schum for his Fernsehgalerie (Television Gallery). Gerry Schulm and Ursula Schum-Weavers, eds., Land Art (Hannover: Hartwig Popp, 1970), n.p. Occurring two months after Earth Art, Land Art included Smithson returning to the quarry across from the Cayuga Salt Mine to create another mirror piece for the exhibition which was filmed and only shown on German Public Television.

- 4The sculptural components are sometimes referred to by different, individual titles including Mirror Displacement; Slant Piece; and Closed Mirror Square.

- 5There is almost no information in any published work on the Subsite/Sub-nonsite. It is rarely mentioned by Smithson in interviews. One photograph included in Mirror Trail has been captioned as “Sub-site Fossil Quarry” with the help of Nancy Holt in Robert Smithson, Robert Smithson: Slideworks, ed. Guglielmo Bargellesi-Severi (Verona: Carlo Frua, 1997), 189. This suggests the sub-site was in the quarry on Portland Point directly across from the Cayuga Salt Mine. Additionally, both the sub-site and sub-Nonsite Mirror Displacements are captured in photographic proof sheets and show Smithson installing the work in the above-specified locations. (from the exhibition archives now at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art).

- 6Smithson created one other Mirror Trail in 1969, at the Paterson Quarry in Paterson, New Jersey. The Cayuga Mirror Trail is the only one, though, which was created in conjunction with a site/Nonsite project. Smithson would remain interested in sites of in-use and abandoned mines, but he would never again actually work in the interior of one. Smithson proposed the idea of a subterranean screening space in Towards the Development of a Cinema Cavern or the movie goer as spelunker (1971), but this was never realized.

- 7This salt mine, still in operation today under Cargill Inc., was dug in 1968 to 2,300 ft., running for miles at this level underground. The mine is one of the only industrial sites in the Ithaca area. It stretches for forty miles under the lake, and is the deepest rock-salt mine in North America.

- 8Robert Smithson, Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack D. Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 189.

- 9Ibid. Gary Shapiro takes this notion of the mine as a dark and disorienting place a step further by suggesting it is a place of complete blindness. While his statement that “The mirrors in the mine were blind or inoperative, because in normal conditions there was no illumination to allow visible reflections,” is gripping, it unfortunately seems to ignore the fact that as a functioning mine, Cayuga Salt Mine was lit. Though part of the power of Smithson’s subterranean mirror displacement comes from the fact that there is as much visible as invisible in this space, the photographs Smithson chose to represent it shows clear visible reflections. Gary Shapiro, Earthwards: Robert Smithson and Art after Babel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

- 10Lipke writes that the Smith called this part of the project “A Mirror Trail with Mirror Displacements from the White Art Museum to the Cayuga Salt Works.” William Lipke, “Notes,” courtesy of Holt/Smithson Foundation, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

- 11The eight locations were as follows: A: A.D. White Museum; B: U.S. Naval Reserve; C: McKinney’s Point; D: Esty Point; E: East Circle Drive/ Route 34; F: Teeter Rd./Portland Pt.; G: Sub-site Fossil Quarry; H: Cayuga Salt Works (the building you see reflected in the mirror). Smithson, Robert Smithson: Slideworks, 188-89.

- 12Smithson, Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, 191.

- 13 Hobbs, 132.

- 14Smithson wrote, “I am interested in the photograph as a material as well as on-the-spot experience. One is sensate and one is more an arrested moment.” Smithson, Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, 236.

Sullivan, Marin R. "Transient Materiality: Robert Smithson’s 'Cayuga Salt Mine Project.'" Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 1 (November 2019). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/transient-materiality-robert-smithsons-cayuga-salt-mine-project.