Nancy Holt’s "Ventilation System" (1985–1992)

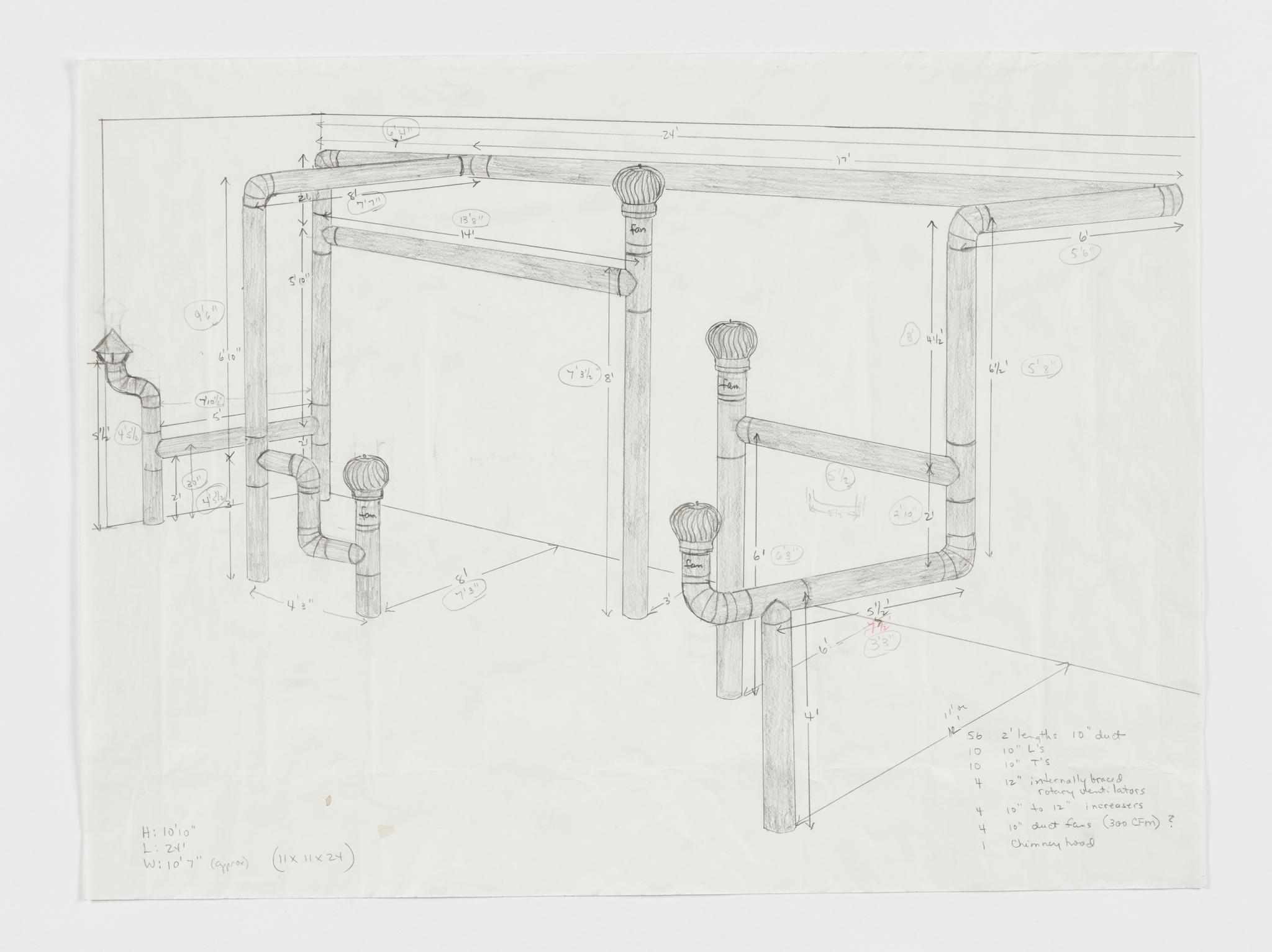

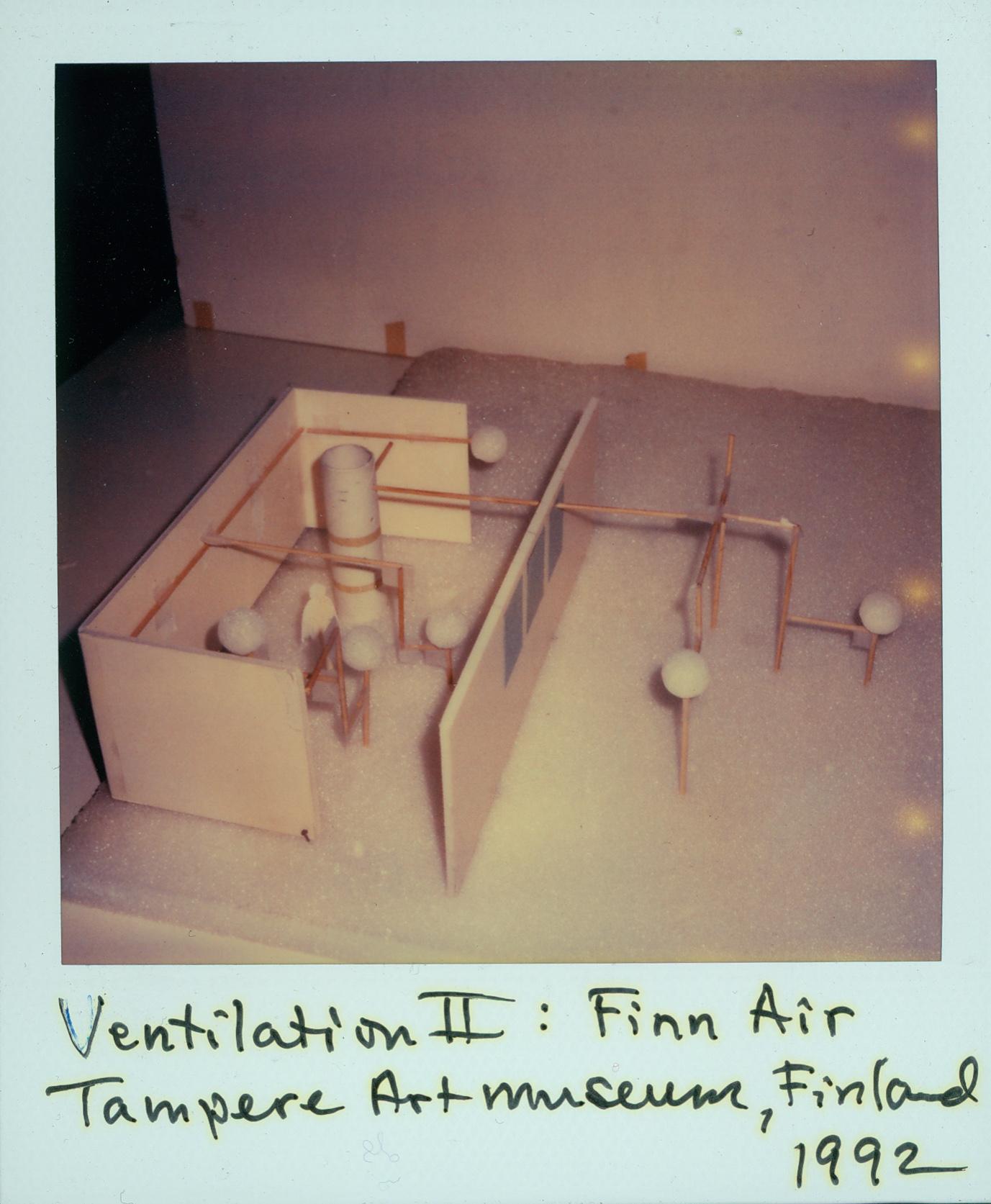

First conceived in 1985, Nancy Holt’s Ventilation System is a site-responsive installation in which interconnected industrial-scale stainless steel ducts channel airflow in and out of a gallery space. Holt’s intention for the work was for it “to be practical yet playful, functional yet not really necessary, a part of the architecture yet part of the outdoor environment as well”1 and such dualities are key to understanding the work’s tone.

Bulky HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems, designed to regulate indoor temperature, air quality, and humidity, are typically the disguised and utilitarian respiratory tracts of a building. Architects often strive to render these services invisible, concealing them behind walls and ceilings, much like the water and gas piping and the electrical wiring flowing above our heads or under our feet in urban and rural landscapes alike. Yet Holt celebrates these networks that are often “relegated to the realm of the unconscious”2 by underlining our dependency on them, while subtly alluding to ecological concerns and the environmental damage caused by human technological advancements. In works related to Ventilation System, including Electrical Lighting for Reading Room (1985) and Pipeline (1986)—all part of Holt’s series of “System Works” exploring human-made infrastructures—she also repurposes readily available, mass-produced, and otherwise unremarkable materials from the building industry. Formally and materially, Ventilation System could be related to Charlotte Posenenske’s explorations of industrial components in the late 1960s, notably her galvanized sheet metal sculptures, such as Series D (1967), that resemble ventilation ducts. However, Posenenske’s modular sculptures pursued her artistic concerns around serial repetition; she delegated compositional agency to visitors and, ultimately, posed a critique of labor. Conceptually and practically, Holt’s concerns took a different pathway.

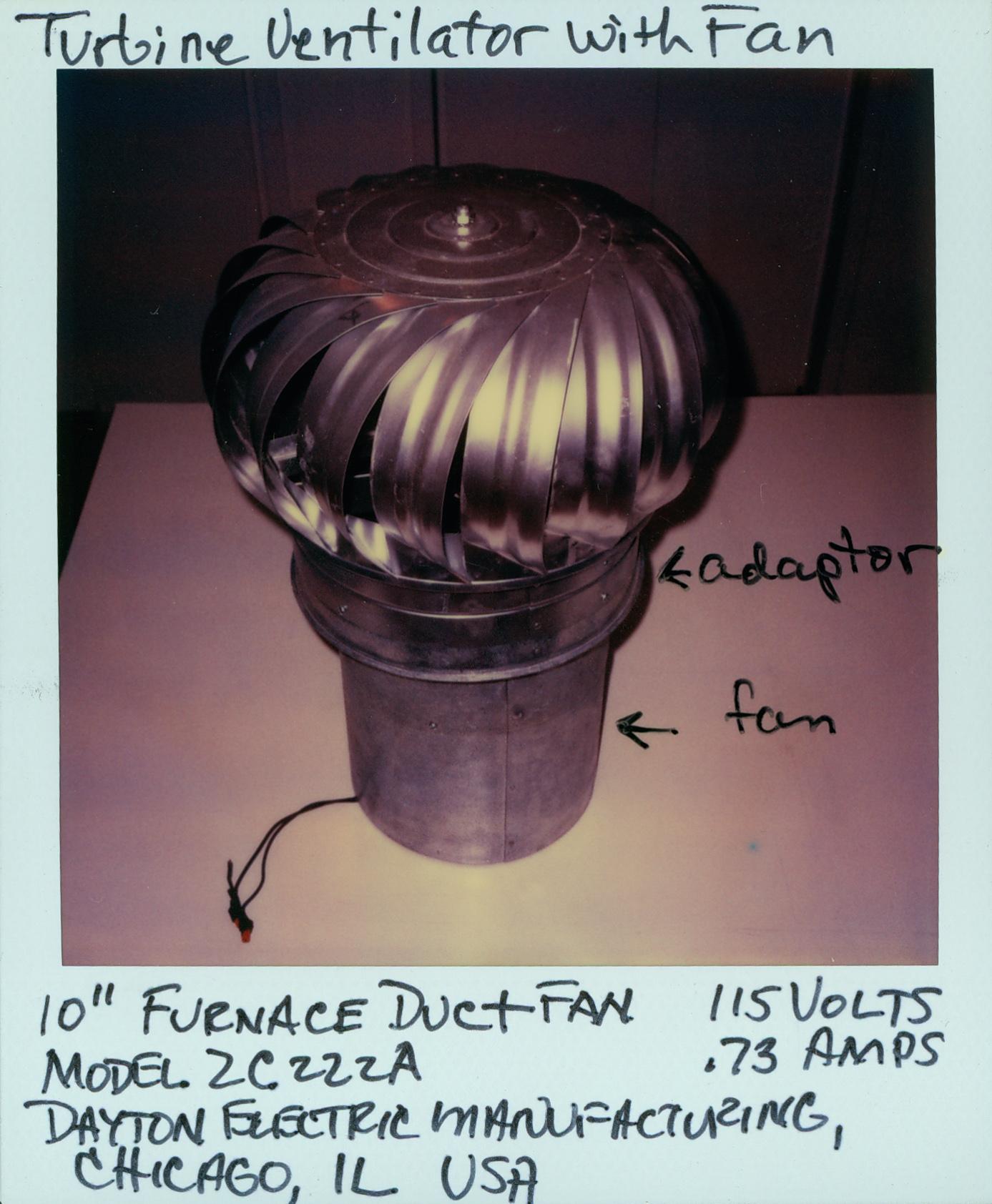

Fabricated with standard industrial components, Holt’s Ventilation System on the one hand seems to perform the “practical” and “functional” aspects of the hardware it references. The piece draws viewers’ attention to the invisible flows that circulate within the built environment, directing breezes through it and into the exhibition space, evidenced by the continuous spinning of the ventilator turbines atop each pipe, and accompanied by a subtle hum, as if it was almost imperceptibly breathing. Running in a perpetual “on” mode, Holt’s custom air systems are installed by specialized HVAC technicians rather than art installers, and they observe local building codes to replicate ventilation infrastructure. Yet, on the other hand, their “playfulness” and “unnecessary” nature lies in the fact that, although the gleaming silvery tubes may seem functional, they are merely a pretense.3 The often-awkward positioning of the ducts, seemingly disrupting the intended visitor flow, proudly highlights their non-essential and mischievous character. Ventilation System is, in essence, a sculpture of HVACs. The work in its various iterations plays with our perception4 and expectations of air circulation while disclosing a technology that is part of a system of services that sustain the very life of the modern city: ventilation systems maintain a comfortable indoor environment, both for people and works of art.

Throughout her career, Holt presented four iterations of Ventilation System: at Temple Gallery, Philadelphia; and Palladium, New York (both in 1985); at the Tampere Art Museum, Finland; and at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York (both in 1992). Posthumously, the installation has been presented on three occasions: at Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden; Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia (both in 2022); and most recently at MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain (2023). Each occasion presented distinctive challenges, necessitating either adaptation of the tubular forms to suit the characteristics of each indoor and/or outdoor site and the coordination of international manufacturing from distance, vividly illustrated by handwritten notes scribbled on Polaroids made in preparation for its Finnish iteration. Moreover, skillfully navigating the diverse technical and financial capabilities of each venue was crucial. These factors significantly influenced the scale of the displays, variously imbuing them with an air of considerable ambition or tempered modesty.

Holt acknowledged the connection between the System Works and Sun Tunnels (1973–76), undoubtedly her best-known project. She conceived of the latter as being part of the solar system, and it reflected her lifelong interest in “bringing the universe to the human being.”5 A similar connection could also be drawn between Ventilation System and meteorological conditions. Its microclimate is ultimately part of global weather systems driven by solar energy. Holt’s inquisitive focus revolved around the pervasive presence, and readymade nature, of technological systems. By employing elements from the plumbing, electrical, drainage, heating, and ventilation industries, she aimed to cultivate a “greater awareness” of our “total dependence” on these systems, and their role in mediating “the channeling of the energy and elements of the earth.”6 Ultimately, her intent was to advocate for how these systems could be “intelligently” used “with the long-term benefit of the planet in mind.” And through such interventions, she pointed at a potential shift in humanity’s relationship with the natural world, from one of extraction to one of stewardship.

In the context of a post-pandemic world characterized by a heightened awareness of the interdependence between the wellbeing of our species and planetary health, a salient argument can be made for revisiting Holt’s emphasis on ecological concerns.7 Amid unprecedented environmental challenges, compelling calls to action have continued to emerge, igniting waves of artistic and institutional responses that prioritize sustainability across operations. A prime example of such a call to action in the art sector is Getting Climate Control Under Control Declaration initiated in 2023, a campaign spearheaded by artists and museum professionals.8 It highlights the significant environmental impact of climate control systems in museums, and how they often account for 60% or more of an institution’s energy expenditure.9 By adjusting temperature and humidity conditions, the declaration points out, museums have the potential to save between 24% and 82% of their consumption. The unprecedented rise in energy costs and mounting pressure to reduce carbon footprints have compelled organizations worldwide to re-evaluate their energy policies.10 This has resulted in a recalibration of previously stringent loan agreements, allowing for the storage and exhibition of objects and artifacts at higher temperatures. This shift, however, has encountered resistance amongst risk-averse museum conservators and insurance companies concerned about potential damage to artworks. Paradoxically, this conversation around conservation and temperature control is occurring at a time when some art institutions in both colder and warmer latitudes have been designated as “climate shelters,” repurposing public facilities to provide thermal comfort to vulnerable citizens during extreme weather conditions.11

The high energy use of art institutions has also sparked a broader debate concerning building inefficiency. Frequently afflicted by outdated architecture—poor insulation or structures not purpose-built for climate control—the bricks-and-mortar of cultural institutions often require costly adaptations and continual maintenance. This financial burden is particularly acute at a time when resources are already strained or subject to cuts. In this context, the work of Chicago-based artist Nick Raffel offers a provocative contribution to this ongoing conversation on energy dynamics within art institutions. Raffel’s art adeptly interplays with its environs, modeling and intervening in the flow of air within buildings and prompting a critical reflection on their efficiency, sustainability, and health impacts.

In 2023, Raffel’s sculptural installation fan (Wesleyan) (2022) was exhibited in the Venetian venue of Fondazione Prada. Crafted from balsa wood and carbon fiber, Raffel’s high-volume, low-speed (HVLS) fan, strategically positioned in the ceiling of the 18th-century Ca' Corner della Regina palazzo, addressed the stagnant air flow while gently swaying the neighboring artist’s draping canvas paintings.12 Notably, its bi-directional design facilitated upward or downward air circulation depending on the season, showcasing its adaptability and efficiency in mitigating energy consumption by mixing stratified air. He employs computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations to model the intricate fluctuation of air circulation, acknowledging the caveat that no space is a pristine vacuum devoid of environmental influences. An earlier version of Raffel’s ventilation works, wind dial (Pied-à-Terre) was presented in 2021 at Pied-à-Terre in San Francisco. This venue lacked any thermal exchange, operable windows, or exhaust. Recognizing the building as a “convectible mechanism,”13 Raffel positioned a passive ventilator colloquially known as a whirlybird on its exterior. This strategic placement created pressure differentials, inducing the flow of air into the gallery space.

In the face of today’s pressing ecological challenges, Raffel’s artistic endeavors sensitize us to the significance of air quality for our collective welfare. Moreover, it could be argued that Raffel’s approach goes beyond Holt’s examinations around perceiving our own perception, to encompass a multifaceted exploration that posits art as a critical site of engagement to create material change. Curator Karen Archey has outlined the distinctions between what she has termed the first, second, and third waves of Institutional Critique artists spanning over sixty years of history—from the 1960s to today. It is intriguing to compare the generational parallels and differences between Holt who, generationally-speaking, would belong to the first wave, and Raffel, to the third. Broadly speaking, while the first wave recognized the ideological apparatus of the institution as a site where political, social, and economic interests are entangled, “the third wave posits the artist foremost as a person in relation to their surrounding material reality, which makes it possible, or not, to create artwork, be productive and live a fulfilling life. The sphere that earlier iterations of Institutional Critique considered is thus broadened to include the very conditions of life, while still examining systems and structures as objects of critique.”14

Ghislaine Leung’s art also navigates the material and structural circumstances that shape the “conditions of life,” particularly artistic labor, by exposing her vulnerability and limitations as an artist. Her practice is expressed through concise sets of conditions referred to as “scores,” outlining the terms of each artwork’s presentation, that the presenting institution interprets and performs in dialogue with the artist. Although the conceptual methodology of text-based scores might align with the first wave of Institutional Critique artists, she has notably adopted the term “constitutional critique” to describe her approach, thereby “dispensing with the pretense that it was possible to occupy a fully detached, reflexive critical position toward an institution while working within it.”15 Yet one can also interpret her method as a sustainable art-making policy as situations are created, sourced, and tuned locally. The score of Violets 2 (2018) states:

“All pipes removed for refurbishment reinstalled within the space of one room and bracketed fixed to the floor, using as much of the material as possible while keeping it all interconnected. Spare pieces that do not fit in this configuration are to be bracketed together in smaller formations. A welcome sign to be installed.”16

The work was first presented as an installation in the Belgian art center Netwerk Aalst, whose space is located on the floor above its original bar, a venue whose ventilation system had been removed after the imposition of a smoking ban rendered it obsolete. The pipes mirrored their former selves, although their ontological status had forever and decisively been altered from discarded aluminum conduits, brackets, screws, bolts, and dirt, to sculpture. Yet in doing so, the art object does not circulate around Holt’s idea of site-specificity but rather operates as being “context-contingent,”17 as Leung has described. Its execution has adapted to the institutional conditions and affordances that have shaped each further iteration, including presentations at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (2019), and Simian, Copenhagen (2023).

Holt’s Ventilation System presciently anticipated the critical urgency of responsible environmental practices, a notion currently gaining traction in the art world and broader societal discourse. Nevertheless, while Holt’s art and that of her contemporaries primarily had a symbolic relationship with such concerns, present and future generations of practitioners are compelled to create amidst a clearer and more present threat of ecosystem collapse. The climate crisis looms as a paramount consideration across all creative pursuits, exerting influence over everything from conceptualization to material choices, and extending to encompass the very frameworks of institutional production and presentation. As writer Amitav Ghosh articulates, “the climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.”18 In this deranged period of accelerating carbon emissions, surmounting deeply entrenched political and socioeconomic structures necessitates art’s capacity for reigniting and rejuvenating its forms, and for both technological innovation and symbolic action.

Selected Bibliography

Micky Donnelly, Nancy Holt Interview, Circa #11 (July/August 1983): 9.

Nancy Holt, “Ventilation Series.” In Nancy Holt: Sightlines, edited by Alena J. Williams, University of California Press, 2011, page 144. Originally published as “Nancy Holt: Ventilation Series” in Christina M. Strassfield, Volume 6, Contemporary Sculptors, exhibition catalogue, unpaginated, East Hampton, N.Y., Guild Hall Museum, 1992.

Nancy Holt, "Ecological Aspects of My Work," Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues catalog, Gail Gelburd, Council for Creative Projects, New York, 1993. Reprinted in Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre, ed.: Nancy Holt/Inside Outside, Monacelli Press, 2021, pp. 197-201.

Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre, ed.: Nancy Holt/Inside Outside, Monacelli Press, 2021.

Joan Marter, Systems: A Conversation with Nancy Holt, Sculpture Magazine vol. 32, no. 8 (October, 2013).

About the Author

Mariana Cánepa is a curator and co-founder, with Max Andrews, of Latitudes in Barcelona, Spain. Latitudes’ recent projects include exhibitions at MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (2021 & 2016); Fabra i Coats: Centre d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (2020 & 2018); and CAPC Musée d’art Contemporain de Bordeaux (2017). She is an Active Member of Gallery Climate Coalition.

With support from Henry Luce Foundation

This Scholarly Text is supported by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to further our public-facing research into the art and ideas of Nancy Holt.

- 1Nancy Holt, “Ventilation Series.” In Nancy Holt: Sightlines, edited by Alena J. Williams, University of California Press, 2011, page 144. Originally published as “Nancy Holt: Ventilation Series” in Christina M. Strassfield, Volume 6 Contemporary Sculptors, exhibition catalogue, unpaginated, East Hampton, N.Y.: Guild Hall Museum, 1992.

- 2Ibid.

- 3Ventilation III: Finn Air (1992) was the only iteration in which there was an actual interchange of indoor and outdoor air. As Holt explained “the Guild Hall piece [”Ventilation IV Hampton Air”, 1992] strongly evoked the inside/outside connection, but it didn’t penetrate the wall. In Finland, there was an interchange of indoor and outdoor air.” Marter, Joan. “Systems: A conversation with Nancy Holt,” Sculpture Magazine, vol. 32, no. 8 (October 2013), page 31.

- 4Holt often described herself as a perception artist. While she preferred to move away from categorizations, art literature often describes her as a pioneer of site-specific installation and the moving image, and as a key member of the earth, land and conceptual art movements.

- 5Ibid.

- 6 Nancy Holt, "Ecological Aspects of My Work", Creative Solutions to Ecological Issues catalog, Gail Gelburd, Council for Creative Projects, New York, New York, 1993, in Lisa Le Feuvre and Katarina Pierre, ed.: Nancy Holt/Inside Outside, Monacelli Press, 2021, p. 198.

- 7 In 2022, energy prices in the European Union soared to historic highs, driven by a global increase in wholesale energy costs exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and escalating international energy demands. Russia's military actions against Ukraine further intensified the situation, leading to a significant rise in gas prices and unprecedented pressure on electricity tariffs across the EU. Concurrently, heatwaves heightened energy demand for cooling while drought-induced limitations on hydropower generation constrained energy supply. These soaring energy costs highlighted the urgent need for sustainable energy strategies amidst the escalating challenges posed by climate change. See infographics https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/energy-prices-2021/ Last accessed April 28, 2024.

- 8Getting Climate Control Under Control was initiated in 2023 by artist Tino Sehgal, ART 2030, and Ki Culture to promote real climate action within museum practices to reduce carbon emissions by 50% by 2030 and was soon supported by organizations such as CIMAM or the Gallery Climate Coalition. More on https://www.art2030.org/projects/getting-climate-control-under-control Last accessed April 28, 2024.

- 9Ibid.

- 10Alex Marshall's New York Times article “As Energy Costs Bite, Museums Rethink a Conservation Credo” provides recent examples of museums suspending minimum temperature requirements for works. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/arts/design/museums-energy-climate-control.html, 1 February 2023. Last accessed April 28, 2024.

- 11 This practice was implemented in 2019 by the Barcelona City Hall and has been progressively adopted by different cities around the world. Smartphone apps such as Extrema use real-time satellite input, along with other city-specific data to estimate the temperature, humidity, and discomfort index in different cities.

- 12The work was included in the exhibition Everybody Talks About the Weather curated by Dieter Roelstraete at Fondazione Prada, Venice, May 20–November 26, 2023.

- 13Raffel in conversation with Benjamin Chaffee, December 8, 2021. Handout for “Nick Raffel: Airfoil” exhibition at the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University Center for the Arts, Middletown, Connecticut, September 6–October 16, 2022.

- 14Karen Archey, After Institutions, Floating Opera Press, 2022, p. 78.

- 15 Rachel Wetzler, “The art of Ghislaine Leung”, Artforum, vol. 62, No. 9, May 2024. Last accessed June 4, 2024.

- 16See https://netwerkaalst.be/en/exhibition/violets-2/ Last accessed June 4, 2024.

- 17Alan Ruiz, “Context Contingent: Ghislaine Leung Interviewed”, BOMB magazine, March 20, 2019. Last accessed June 4, 2024.

- 18Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, The University of Chicago Press, 2016, p. 9.

Cánepa Luna, Mariana. "Nancy Holt’s "Ventilation System" (1985–1992)." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 7 (October 2024). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/nancy-holts-ventilation-system-1985-1992.

![Ventilation III: Finn Air [indoor section] (1992)](/sites/default/files/styles/fullscreen_2048_x_y_/public/2024-10/Ventilation-III_01.jpg?itok=AVblxWSL)

![Nancy Holt, Ventilation IV: Hampton Air [indoor section] (1992)](/sites/default/files/styles/fullscreen_2048_x_y_/public/2024-10/Ventilation-IV_16.jpg?itok=_qdOTIJj)

![Nancy Holt, Ventilation IV: Hampton Air [outdoor section] (1992)](/sites/default/files/styles/fullscreen_2048_x_y_/public/2024-10/Ventilation-IV_01.jpg?itok=4WTHyDoE)