A Museum of Langauge in the Vicinity of Art

She took one or two of them down and turned the pages over trying to persuade herself she was reading them. But the meanings of words seemed to dart away from her like a shoal of minnows as she advanced upon them, and she felt more uneasy still.

—Michael Frayn, Against Entropy

Ad Reinhardt: “The Four Museums are the Four Mirrors”

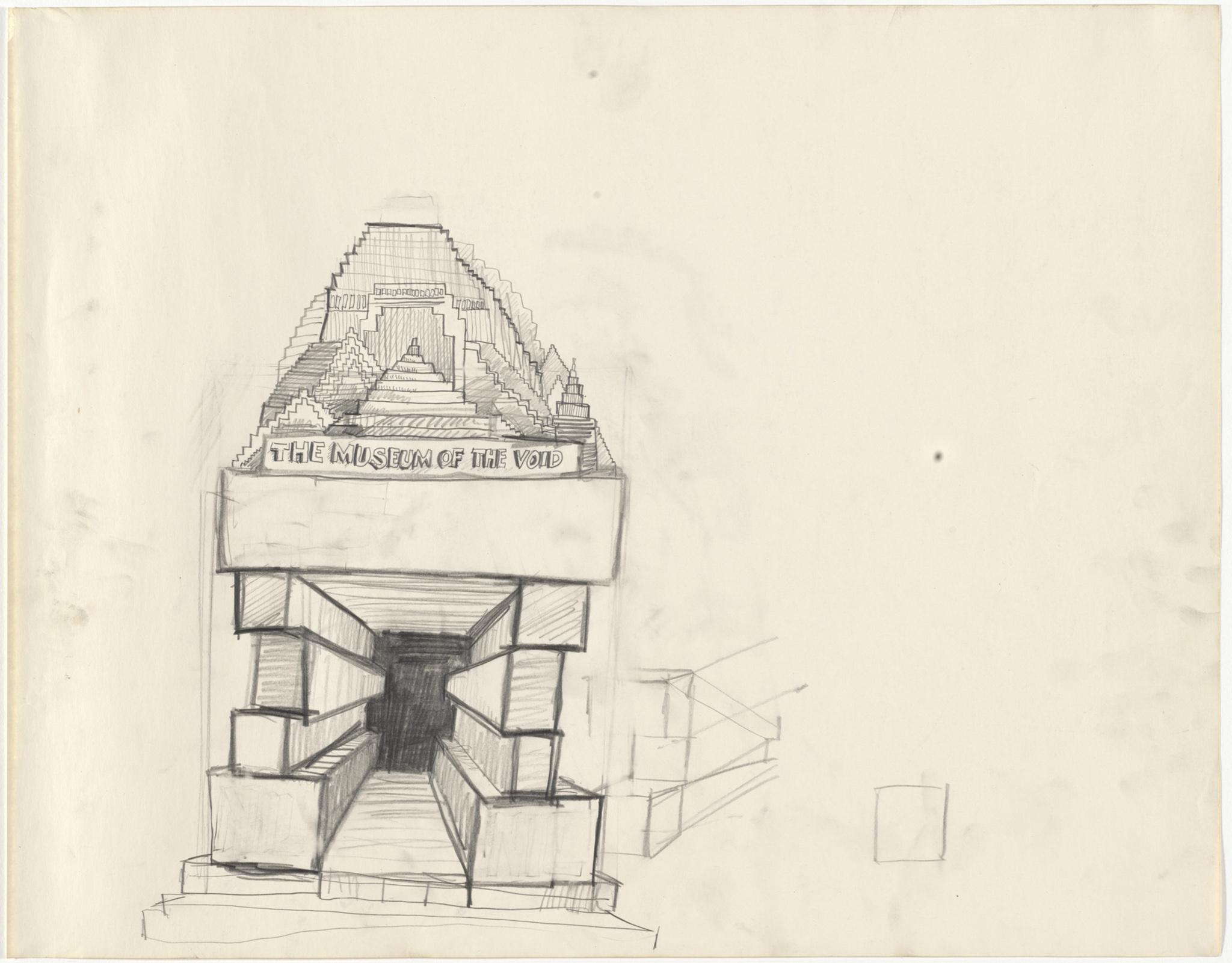

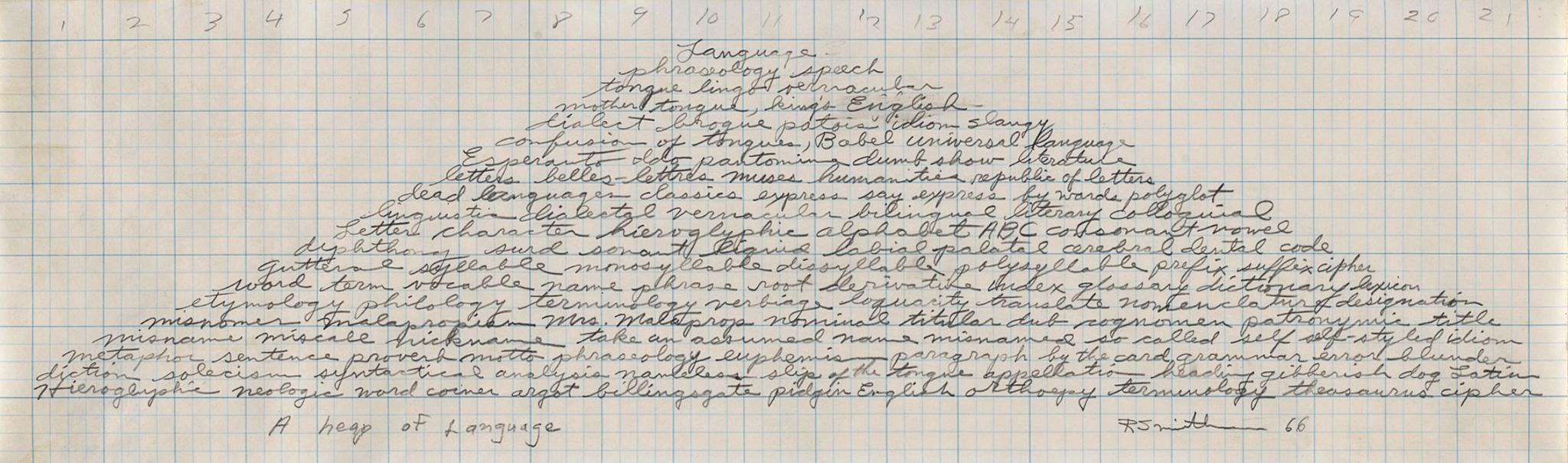

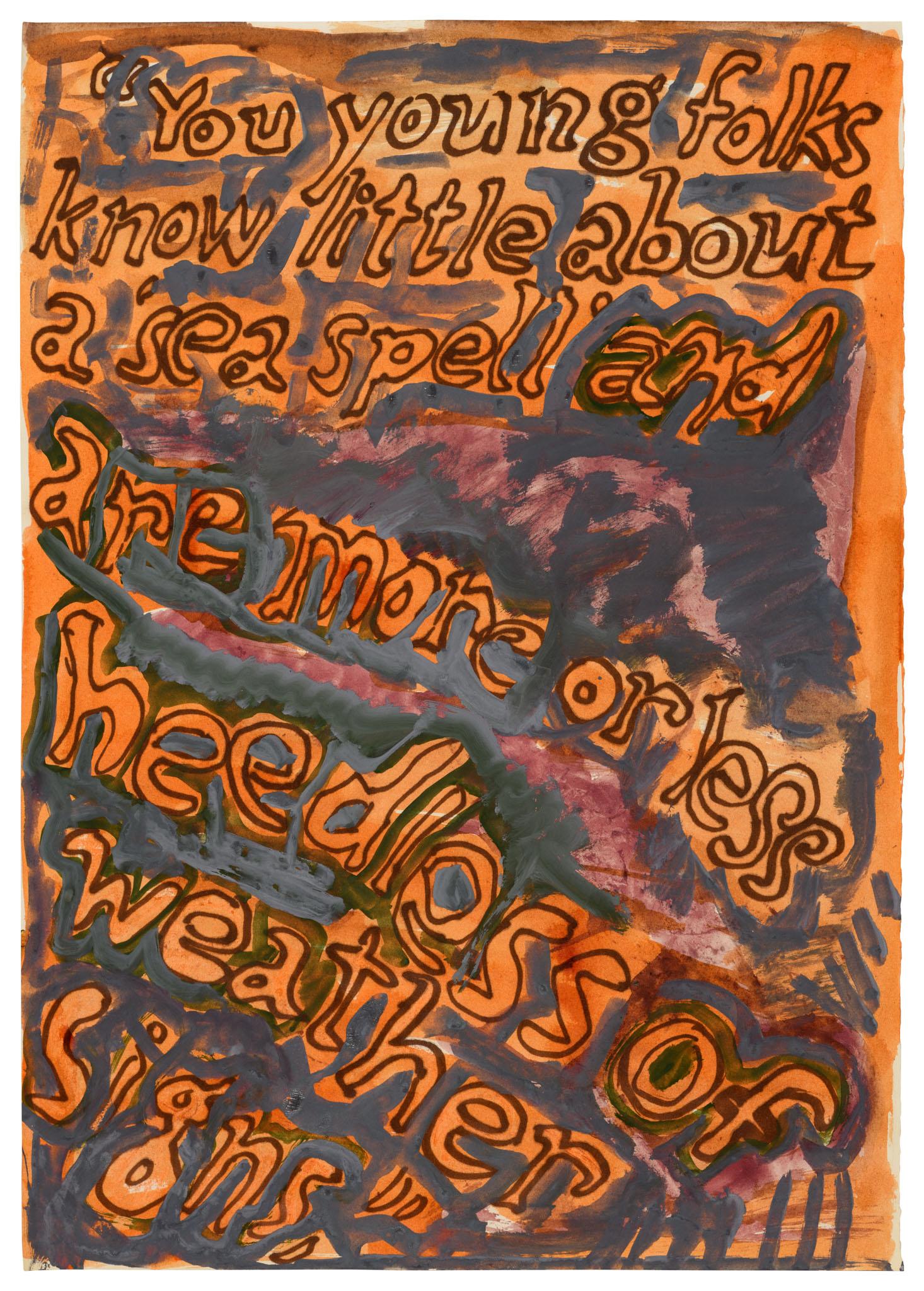

In the illusory babels of language, an artist might advance specifically to get lost, and to intoxicate himself in dizzying syntaxes, seeking odd intersections of meaning, strange corridors of history, unexpected echoes, unknown humors, or voids of knowledge… but this quest is risky, full of bottomless fictions and endless architectures and counter-architectures … at the end, if there is an end, are perhaps only meaningless reverberations. The following is a mirror structure built of macro and micro orders, reflections, critical Laputans, and dangerous stairways of words, a shaky edifice of fictions that hangs over inverse syntactical arrangements … coherences that vanish into quasiexactitudes and sublunary and translunary principles. Here language “covers” rather than “discovers” its sites and situations. Here language “closes” rather than “discloses” doors to utilitarian interpretations and explanations. The language of the artists and critics referred to in this article becomes paradigmatic reflections in a looking-glass babel that is fabricated according to Pascal’s remark, “Nature is an infinite sphere, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” The entire article may be viewed as a variation on that much misused remark; or as a monstrous “museum” constructed out of multi-faceted surfaces that refer, not to one subject but to many subjects within a single building or words – a brick = a word, a sentence = a room, a paragraph = a floor of rooms, etc. Or language becomes an infinite museum, whose center is everywhere and whose limits are nowhere.

MARGINALIA AT THE CENTER: INFRA-CRITICISM

Dan Flavin deploys writing as a pure spectacle of attenuation. Flavin’s autobiographical method is mutated into a synthetic reconstitution of memories, that brings to mind a vestigial history. “Now there are battered profiles of boxers with broken noses and Dido’s pyre on a wall in Carthage, its passionate smoke piercing pious Aeneas’ faithless heart outbound in the harbor below.” (…in daylight or cool white, “Artforum,” December 1965.) Flavin’s Carthage is an arsenal of expired metaphor and fevered reverie. His grandiloquent remembrances play on one’s poetic sense with a mournful giddiness. In his sentence we find disarming uselessness that echoes the outrages of Salammbô. “The walls were covered with bronze scales; and in the midst, on a granite pedestal, stood the statue of the Kabiri called Aletes, the discoverer of the mines in Celtiberia. On the ground, at its base, and arranged in the form of a cross, lay broad gold shields and monstrous silver vases with closed necks, of extravagant shape and of no possible use …” Flavin’s writings like Flaubert’s “vases” are of “no possible use.” Here we have a chronic case of mental immobilization that results in leaden lyrics. Language falls toward its final dissolution like the sullen electricities of Flavins “lights.” His slapstick “letters to the editor” also call forth the assorted humors of Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pecuchet –the quixotic autodidacts.

Carl Andre’s writings bury the mind under rigorous incantatory arrangements. Such a method smothers any reference to anything other than the words. Thoughts are crushed into a rubble of syncopated syllables. Reason becomes a powder of vowels and consonants. His words hold together without any sonority. Andrew doesn’t practice a “dialectical materialism,” but rather a “metaphorical materialism.” The apparent sameness and toneless ordering of Andre’s poems conceals a radical disorientation of grammar. Paradoxically his “words’ are charged with all the complication of oxymoron and hyperbole. Each poem is a “grave,” so to speak, for his metaphors. Semantics are driven out of his language in order to avoid meaning.

Robert Morris enjoys putting sham “mistakes” into his language systems. His dummy File for example contains a special category called “mistakes.” At times, the artist admits it is difficult to tell a real mistake from a false mistake. Nevertheless, Morris likes to track down the “irrelevant” and then forget it as quickly as possible. Actually, he can hardly remember doing the File. Yet, he must have derived some kind of pleasure from preserving those tedious moments, those minute events, that others call “living.” He works from memory which is strange when you consider he has nothing to remember. Unlike an elephant, the artist is one who always forgets.

Donald Judd at one time wrote a descriptive criticism that described “specific objects.” When he wrote about Lee Bontecou, his descriptions became a language full of holes. “The black hole does not allude to a black hole,” says Judd, “it is one.” (Arts, April 1965.) In that article Judd brings into focus the structure of his own notion of “the general and the specific” by defining the “central hole” and “periphery” of her “conic scheme.” Let us equate central with specific, and general with periphery. Although Judd is “no longer interested in voids,” he does seem interested in blank surfaces, which are in effect the opposite of voids. Judd brings an “abyss”1 into the very material of the thing he describes when he says: “The image is an object, a grim, abyssal one.” The paradox between the specific and the general is also abyssal. Judd’s syntax is abyssal – it is a language that ebbs from the mind into an ocean of words. A brooding depth of gleaming surfaces – placid but dismal.

Sol LeWitt is very much aware of the traps and pitfalls of language, and as a result is also concerned with ennervating “concepts” of paradox. Everything LeWitt thinks, writes, or has made is inconsistent and contradictory. The “original idea” of his art is “lost in a mess of drawing, figurings, and other ideas.” Nothing is where it seems to be. His concepts are prisons devoid of reason. The information on his announcement for his show (Dwan Gallery, Los Angeles, April 1967) is an indication of a self-destroying logic. He submerges the “grid plan” of his show under a deluge of simulated handwritten data. The grid fades under the oppressive weight of “sepia” handwriting. It’s like getting words caught in your eyes.

Ad Reinhardt’s Chronology (Ad Reinhardt – Paintings by Lucy R. Lippard) is a somber substitute for a loss of confidence in wisdom – it is a register of laughter without motive, as well as being a history of non-sense. Behind the “facts” of his life run the ludicrous events of hazard and destruction. A series of fixed incidents in the dumps of time. “1936 Civil War in Spain.” “1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco.” “1964 China explodes atomic bomb.” Along with the inchoate, calamitous remains of those dead headlines, runs a dry humor that breaks into hilarious personal memories. Everything in this Chronology is transparent and intangible, and moves from semblance to semblance, in order to disclose the final nullity. “1966 One hundred twenty paintings at Jewish Museum.” Reinhardt’s Chronology follows a chain of non-happenings – its order appears to be born of a doleful tedium that originates in the unfathomable ground of farce. This dualistic history records itself on the tautologies of the private and the public. Here is a negative knowledge that enshrouds itself in the remote regions of that intricate language – the joke.

Peter Hutchinson, author of “Is There Life on Earth?” (Art in America, Fall 1966), uses the discards of last year’s future in order to define today’s present. His method is highly artificial and is composed of paralyzed quotes, listless theories, and bland irony. His abandoned planets maintain unthinkable “cultures,” and have tasteless “tastes.” In “Mannerism in the Abstract” (Art and Artists, September 1966) Hutchinson lets us know about “probabilities, contingencies, chances, and cosmic breakdown.” “Scientism” is shown to be actually a kind of Mannerist science full of obvious disguises and false bottoms. “Topology surely mocks plane geometry,” says Hutchinson. but actually his language usage deliberately mocks his own meaning, so that nothing is left but a gratuitous syntactical device. His writing is marvelously “inauthentic.” The complexity and richness of Hutchinson’s method starts with science fiction clichés, and scientistic conservations and ends in an extraordinary esthetic structure. To paraphrase Nathalie Sarraute on Flaubert, “Here Hutchinson’s defects become virtues.”

The attraction of the world outside awakens so energetically in me the expansive force that I dilate without limit … absorbed, lost in multiple curiosity, in the infinity of erudition and the inexhaustible detail of a peripheral world.

—Henri-Frédéric Amiel, Journal, 1854

Dan Graham is also very much aware of the fringes of communication. And it is not surprising that one of his favorite authors is Robert Pinget. Graham responds to language as though he lived in it. He has a way of isolating segments of unreliable information into compact masses of fugitive meaning. One such mass of meanings he has disinterred from the tombic art of Carl Andre. Some segments from Carl Andre (unpublished list) are as follows: “frothing at the mouth and from watertaps”; “misconceptions and canned laughter”; “difficulty in grasping.” This is the kind of depraved metaphor that Andre tries to bury in his “blocks of words.” Graham discloses the metaphors that everyone wants to escape.

Like some of the other artists Graham can “read” the language of buildings. (“Homes for America,” Arts, December-January 1967.) The “block houses “of the post-war suburbs communicate their “ ’dead’ land areas” or “sites” in the manner of a linguistic permutation. Andre Martinet writes, “Buildings are intended to serve as protection…” – the same is true of artists’ writings. Each syntax is a “light constructed ‘shell’ ” or set of linguistic surfaces that surround the artist’s unknown motives. The reading of both buildings and grammars enables the artist to avoid out of date appeals to “function” or “utilitarianism.”

Andy Warhol allows himself to be “interrogated”; he seems too tired to actually grip a pencil, or punch a typewriter. He allows himself to be beaten with “questions” by his poet-friend Gerard Malanga. Words for Warhol become something like surrogate torture devices. His language syntax is infused with a fake sadomasochism. In an interview he is lashed by Malanga’s questions (Arts, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1967):

Q: Are all the people degenerates in the movie?

A: Not all the people – 99.9% of them.

Serge Garvronsky writing in Cahiers du Cinema, No. 10, points out that Warhol employs a kind of self-inventing dialogue in his films, that resembles the sub-dialogue of Nathalie Sarraute. Garvronsky points out the “dis-synchronized talk,” “monosyllabic English,” and other “tropistic” effects. The language has no force, it’s not very convincing – all the pornographic preoccupations collapse into verbal deposits, or what is called in communication theory “degenerative information.” Warhol’s syntax forces an artifice of sadomasochism that mimics its supposed “reality.” Even his surfaces destroy themselves. In Conversation and Sub-conversation 1956 by Nathalie Sarraute we find out something about “pointless remarks,” and dialogue masses, that shape our experience “the slightest intonations and inflections of voice,” that become maps of meaning or antimeaning. Said Bosley Crowther (New York Times, July 11, 1967) in a review of My Hustler, “I would say that ‘The Endless Conversations’ would be a better title for this fetid beach-boy film.”

Edward Ruscha (alias Eddie Russia) collaborated with Mason Williams and Patrick Blackwell on a book, Royal Road Test, that appears to be about the sad fate of a Royal (Model “X”) typewriter. Here is no Warholian sloth, but rather a kind of dispassionate fury. The book begins on a note of counterfeit Russian nihilism, “It was too directly bound to its own anguish to be anything other than a cry of negation; carrying within itself the seeds of its own destruction.” A record of the deed is as follows:

Date: Sunday, August 21, 1966

Time: 5:07 p.m.

Place: U.S. Highway 91 (interstate Highway 15), traveling south-southwest approximately 122 southwest of Las Vegas, Nevada

Weather: Perfect

Speed: 90 m.p.h.

The typewriter was thrown from a 1963 Buick window by “thrower” Mason Williams. The “strewn wreckage” was labeled and photographed for the book.

INVERSE MEANINGS – THE PARADOXES OF CRITICAL UNDERSTANDING

Modern art, like modern science, can establish complementary relations with discredited fictional systems; as Newtonian mechanics is to quantum mechanics, so King Lear is to Endgame.

—Frank Kermode, The Sense of Ending

How can anyone believe that a given work is an object independent of the psyche and personal history of the critic studying it, with regards to which he enjoys a sort of extraterritorial status?

—Roland Barthes, Criticism as Language

Materialism. Utter the word with horror, stressing each syllable.

—Gustave Flaubert, The Dictionary of Accepted Ideas

When the word “fiction” is used, most of us think of literature, and practically never of fictions in a general sense. The rational notion of “realism,” it seems, has prevented esthetics from coming to terms with the place of fiction in all the arts. Realism does not draw from the direct evidence of the mind, but rather refers back to “naturalistic expressiveness” or “slices of life.” This happens when art competes with life, and esthetics is replaced by rational imperatives.

The fictional betrays its privileged position when it abdicates to a mindless “realism.” The status of fiction has vanished into the myth of the fact. It is thought that facts have a greater reality than fiction – that “science fiction” through the myth of progress becomes “science fact.” Fiction is not believed to be a part of the world. Rationalism confines fiction to literary categories in order to protect its own interests or systems of knowledge. The rationalist, in order to maintain his realistic systems, only ascribes “primary qualities” to the world.

The “materialist” Carl Andre calls his work “a flight from the mind.” Andrew says that his “poems” and “sculpture” have no mental or secondary qualities, they are to him solidly “material.” Yet paradoxically, Lucy Lippard writing in The New York Times, June 4, 1967, suggests that Andre’s sculpture in a show at the Bykert Gallery is “rebelliously romantic” because of “nuance” and “surface effects.” One person’s “materialism” becomes another person’s “romanticism.” I would venture to assert at this point, that both Miss Lippard’s “romanticism” and Andre’s “materialism” are the same thing. Both views refer to private states of consciousness that are interchangeable.

Romanticism is an older philosophical fiction than materialism. Its artifices are to a greater degree more decadent than the inventions of materialisms, yet at the same time it is more familiar and not as threatening to the myths of fact as materialism. For some people the mere mention of the word “materialism” evokes hordes of demonic forces. Romanticism and materialism if viewed with two-dimensional clarity have a transparence and directness about them that is highly fictive. Peter Brook recognized this esthetic in Robbe-Grillet. Says Brook, “If Robbe-Grillet has sought to destroy the ‘romantic heart of things,’ there is a sense in which he is constantly fascinated by the romanticism of surfaces, a preoccupation especially noticeable in the films Marienbad and L’Immortelle, and quite explicit in his new novel, La Maison de rendezvous.” (Partisan Review, Winter 1967.) The same is true of “materialism” when it becomes the esthetic motive of the artist. The reality of materialism is no more real than that of romanticism. In a sense, it becomes evident that today’s materialism and romanticism share similar “surfaces.” The romanticism of the 60s is a concern for the surfaces of materialism, and both are fictions in the chance minds of the people who perceive them. If scientism isn’t being used or misused, then what I will call “philosophism” is. Philosophism confuses realism with esthetics, and defines art apart from any understanding of the artifices of the mind and things.

Much modern art is trapped in temporality, because it is unconscious of time as a “mental structure” or abstract support. The temporality of time began to be imposed on art in the 18th and 19th centuries with the rise of realism in painting and novel writing. Novels cease being fictions, criticism condemns “humoral” categories, and “nature” acts as the prevailing panacea. The time consciousness of that period gave rise to thinking in terms of Renaissance history. Everett Ellin in a fascinating article “Museums as Media” (ICA Bulletin, May 1967), “The museum, a creation of the 19th century, quite naturally adopted the popular mode of the Renaissance for its content.” Time had yet to extend into the distant future (post-history) or into the distant past (pre-history) – nobody much though about “flying saucers” or an Age of Dinosaurs. Both pre- and post-history are part of the same time consciousness, and they exist without any reference to Renaissance history. I had a slight awareness of the sameness of pre- and post-history, when I wrote in “Entropy and the New Monuments” (Artforum, June 1966), “This sense of extreme past and future has its partial origin in the Museum of Natural History; there the ‘cave man’ and the ‘space man’ may be seen under one roof.” It didn’t occur to me then, that the “meanings” in the Museum of Natural History avoided any reference to the Renaissance, yet it does show ‘art” from the Aztec and American Indian periods – are those periods any more or less “natural” than the Renaissance? I think not – because there is nothing “natural” about the Museum of Natural History. “Nature” is simply another 18th- and 19th- century fiction. Says E.E. Cummings, “Natural history museum are made by fools unlike me. But only God can stuff a tree…” (“Letter to Ezra Pound,” Paris Review, Fall 1966.) The “past-nature” of the Renaissance finds its “future-nature” in Modernism – both are founded on realism.

RESTORATIONS OF PREHISTORY

The prehistory one finds in the Museum of Natural History is fugitive and uncertain. It is reconstructed from “Epochs” and “Periods” that no man has ever witnessed and based on the remains of “animated beings” from the Trilobites to Triceratops. We vaguely know about them through Walt Disney and Sinclair Oil – they are the dinosaurs. One of the best “recreators” of this “dinosaurism” is Charles R. Knight. In many ways he excels the Pop artists, but he comes closest to Claes Oldenburg, at least in terms of scale. Sinclair Oil ought to commission Oldenburg to make “the mating habits of the Brontosaurus” for children’s sex education. Knight’s art is never seen in museums outside of the M.N.H., because it doesn’t fit in with the contrived “art-histories” of Modernism or the Renaissance.

Knight is also an artist who writes. In Life Through the Ages, a book of 28 prehistoric “time” restorations, Knight can be seen as a combination Edouard Manet and Eric Temple Bell (the professor of Mathematics who wrote science fiction for Wonder Stories Magazine). Bell in The Greatest Adventure describes “brutes” that are “like no prehistoric monster known to science.” These monsters are “piled five and six deep” on a frozen beach in Antarctica. “They are like bad copies, botched imitations if you like of those huge brutes whose bones we chisel out of the rocks from Wyoming to Patagonia. Nature must have been drunk, drugged or asleep when she allowed these aborted beasts to mature. Every last one of them is a freak.” It is hard to say Knight’s monsters are “bad copies,” yet there is something odd and displaced about both his writings and art. He refers to his writings as “captions,” and to his art as “the more striking forms of Prehistoric times.” The following quote is from Knight’s “The Carboniferous or Coal Period” – “Great sprawling salamander-like creatures such as Eryops are typical of the period. No doubt these and many other species still passed their earlier life stages in the water. They were stupid smooth-skinned monsters some six feet long, with wide tooth-filled jaws and an enormous gape which enabled them to swallow their food at a single gulp.” He also has a way of evoking the prehistoric landscape – “Rancho La Brea – California Pitch Pools”: “Peaceful as the place looks now, tragedy, both dark and terrible, long hung about its gloomy depths.” The corollary of Knights’ artifice is immobilization. This heavy prehistoric time extends to the landscape: “slime-covered morasses” and “It was an era of swamps.” Death is suggested in the ever present petrifaction of forests and creatures; a predilection for the oppressive and grim marks everything he writes and draws. One senses an enormous amorphous struggle between the stable and the unstable, a fusion of action and inertia symbolizing a kind of cartoon vision of the cosmos. Violence and destruction are intimately associated with this type of carnivorous evolutionism. Nothing seems to escape annihilation – for the Brontosaurus, “starvation is their greatest bugaboo.” A kind of goofiness haunts these “big bulked and small-brained” saurians. Tyrannosaurus Rex is considered by Knight to be “just an enormous eating machine.” These “sinister beings” seem like reformulated symbols of total or original Evil. The battle between the Tyrannosaurus and Stegosaurus in Walt Disney’s Fantasia set to the music of The Rite of Spring evoked a two-dimensional spectacular death-struggle, quite in keeping with the entire cast of preposterous reptilian “machines.” No doubt, Disney at some point copied his dinosaurs from Knight, just as Sinclair Oil must have copied directly from Disney for their “Dino-the-Dinosaur.”

TERATOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

The Art World was created in 4 Days in 4 Sections, 40 years ago, and originally in 4004 B.C. Today minor artists have 400 Disciples and more favored mediocre Artists have 44,000 Devotees approximately.

—Ad Reinhardt, A Portend of the Artist as a Yhung Mandela

The immensity of geologic time is so great that is difficult for human minds to grasp readily the reality of its extent. It is almost as if one were to try to understand infinity.

—Edwin H. Colbert, The Dinosaur Book

The word “teratology” or “teratoid” when not being used by biology and medicine in an “organic” way has a meaning that has to do with marvels, portends, monsters, mutations and prodigious things (Greek: teras, teratos = a wonder). The word teratoid like the word dinosaur suggests extraordinary scale, immense regions, and infinite quantity. If we accept Ad Reinhard’s “portend,” the Art World is both a monster and a marvel, and if we extend the meaning of the word: a dinosaur (terrible lizard) – a lizard with its tail in its mouth. Perhaps, that is not “abstract” enough for some of the “devotees.” Perhaps they would prefer the “circular earth mound” by Robert Morris or even “a target” by Kenneth Noland. Organic word meanings, when applied to abstract or mental structures have a way of returning art to the biological condition of naturalism and realism. Science has claimed the word teratology and related it to disease. The “marvelous” meaning of that word has to be brought to consciousness again.

Let us now examine Reinhardt’s “Portend” and take this “Joke” seriously. In a sense Reinhardt’s teratological Portend seems to approach some kind of pure classicism, except that where the classicist sees the necessary and true concept of pure cosmic order, Reinhardt sees it as a grotesque decoy. Near a label “NATURALIST-EXPRESSIONIST-CLASSICISM we see “an angel” and “a devil” – and a prehistoric Pterodactyl; Knight calls it “another kind of flying mechanism.” Reinhardt treats the Pterodactyl as an atemporal creature belonging to the same order as devils and angels. The concrete reptile-bird of the Jurassic Period is displaced from its place in the “synoptic Table of the Amphibia and Reptilia” of the “subclass Diapsida,” and transformed by Reinhardt into a demon or possibly an Aeon. The rim of Reinhardt’s Portend becomes an ill-defined set of schemes, entities half abstract, half concrete, half impersonal fragments of time or de-spatialized oddities and monsters, a Renaissance dinosaurism hypostatized by a fictional ring of time – something halfway between the real and the symbolic. This part of the Portend is dominated by a humorous nostalgia for a past that never existed – past history becomes a comic hell. Atemporal monsters or teratoids are mixed in a precise, yet totally inorganic way. Reinhardt isn’t doing what so many “natural expressive” artists do – he doesn’t pretend to be honest. History breaks down into fabulous lies, that reveal nothing but copies of copies. There is no order outside of the mandala itself.

THE CENTER AND THE CIRCUMFERENCE

The center of Reinhardt’s Joke is empty of monsters, a circle contains four sets of three squares that descend toward the middle vortex. It is an inversion of Pascal’s statement, that “nature is an infinite sphere, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere”: instead with Reinhardt we get an Art World that is an infinite sphere, whose circumference is everywhere but whose center is nowhere. The teratological fringe or circumference alludes to a tumultuous circle of teeming memories from the Past – from that historical past one sees “nothing” at the middle. The finite present of the center annihilates itself in the presence of the infinite fringes. An appalling distance is established between past and present, but the mandala always engulfs the present order of things – ART AND GOVERNMENT / ART AND EDUCATION / ART AND NATURE / ART AND BUSINESS – are lost in a freakish grandeur that empties one’s central gaze. Everything mad and grotesque in the outer edges encompasses the present “Art World” in an abysmal concatenation of Baals, Banshees, Beezleboobs, Zealots, Wretches, Toadies, all of which are transformed into horrors of more recent origin. From the central vortex, that looks like prophetic parody of “op art” – I can’t think of anything more meaningless than that – to the rectangular margin of parodic wisdom – “Everybuddie understands the Songs of Birds and Picasso,” one is aware of a conflict between center and perimeter. The excluded idle of this Joke plunges the mind into a simulated past and present without a future. The original and historical nightmare bordering the “void” destroys its own sanctuary. At the bottom of this well we see “nothing.” The center is encompassed by “The Human Vegetable, The Human Machine, The Human Eye, The Human Animal” – a human “prison house of grandeur and glory,” not unlike Edgar Allan Poe’s House of Usher, or even more precisely his A Descent into the Maelstrom – “Upon the interior surface of a funnel vast in circumference, prodigious in depth.” Poe’s “Pit” (center) is defined by the swing of the “Pendulum” from side to side, thus defining the circumference. Reinhardt’s “dark humor” resembles Poe’s “sheeted memories of the past.” Reinhardt maintains the same haunted mind that Poe did: “a dim-remembered story of the old time entombed.”

THE MOVIES OF ROGER CORMAN AND NEGATIVE ETERNITIES

The films of Roger Corman are structured by an esthetic of atemporality, that relates to Reinhardt and Poe more than most visual artists working at this time. The grammar of Corman’s films avoids the “organic substances” and life-forcing rationalism that fills so many realistic films with naturalistic meanings. His actors always appear vacant and transparent, more like robots than people – they simply move through a series of settings and places and define where they are by the artifice that surrounds them. This artifice is always signaled by a “tomb” or another mise en scéne of deathlessness. For instance, the Great Pyramid at the beginning of The Secret Invasion, or the Funeral at the end of The Wild Angels. Duration is drained, and the networks of an infinite mind take over, turning the “location” of the film into “immeasurable but still definite distances” (Poe). Corman brings the infinite into the finite things and minds that he directs. The suburban sites in The Wild Angels appear with a “gleaming and ghastly radiance” (Poe) and seem not to exist at all except in spectral cinematic artifices. The menacing fictions of the terrain engulf the creatures that pass as actors. “Things” in a Corman movie seem to negate the very condition they are presented in. A parodic pattern is established by the conventionalized structure or plot-line. The actors as “characters” are not developed but rather buried under countless disguises. This is especially true of The Secret Invasion, where nobody seems to be anybody. Corman uses actors as though they were “angels” or “monsters” in a cosmos of dissimulation, and it is in that way that they relate to Reinhardt’s world or cosmic view. Corman’s sense of dissimulation shows us the peripheral shell of appearances in terms of some invisibles set of rules, rather than by any “natural” or “realistic” inner motivation – his actors reflect the empty center.

SPECTRAL SUBURBS

Where have all the people gone today? Well, there’s no need for you to be worried about all those people. You never see those people anyway.

—The Grateful Dead, Morning Dew (Dobson-Rose)

… dead streets of the inner suburbs, yellow under the sodium lights.

—Michael Frayn, Against Entropy

In 1954, when they announced the H-Bom, only the kids were ready for it.

—Kurt Von Meier, quoted in Open City

A dry wind blows hot and cold down from Chimborazo a soiled post card in the prop blue sky. Crab men peer out of abandoned quarries and slag heaps…

—William S. Burroughs, The Soft Machine

It seems that “the war babies,” those born after 1937-1938 were “Born Dead” – to use a motto favored by the Hell’s Angels. The philosophism of “reality” ended some time after the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the ovens cooled down. Cinematic “appearance” took over completely sometime in the late 50s. “Nature” falls into an infinite series of movie “stills” – we get what Marshall McLuhan calls “The Reel World.”

Suburbia encompasses the large cities and dislocates the “country.” Suburbia literally means a “city below”; it is a circular gulf between city and country – a place where buildings seem to sink away from one’s vision – buildings fall back into sprawling babels or limbos. Every site glides away toward absence. An immense negative entity of formlessness displaces the center which is the city and swamps the country. From the worn down mountains of North New Jersey to postcard skylines of Manhattan, the prodigious variety of “housing projects” radiate into a vaporized world of cubes. The landscape is effaced into sidereal expanses and contractions. Los Angeles is all suburb, a pointless phenomenon which seems uninhabitable, and a place swarming with dematerialized distances. A pale copy of a bad movie. Edward Ruscha records this pointlessness in his Every Building on the Sunset Strip. All the buildings expire along a horizon broken at intervals by vacant lots, luminous avenues, and modernistic perspectives. The outdoor immateriality of such photographs contrasts with the pale but lurid indoors of Andy Warhol’s movies. Dan Graham gains this “non-presence” and serial sense of distance in his suburban photos of forbidding sites. Exterior space gives way to the total vacuity of time. Time as a concrete aspect of mind mixed with things is attenuated into ever greater distances, that leave one fixed in a certain spot. Reality dissolves into leaden and incessant lattices of solid diminution. An effacement of the country and city abolishes space, but establishes enormous mental distances. What the artist seeks is coherence and order – not “truth,” correct statements, or proofs. He seeks the fiction that reality will sooner or later imitate.

MAPSCAPES OR CARTOGRAPHIC SITES

In the deserts of the West some mangled Ruins of the Map lasted on, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in the whole Country there are no other relics of the Disciplines of Geography.

—Suarez Miranda, Viajes de Varones Prudentes, Book Four, Chapter XLV, Lerida, 1658

… all the maps you have are of no use, all this work of discovery and surveying; you have to start off at random, like the first men on earth; you risk dying of hunger a few miles from the richest stores…

—Michel Butor, Degrees

From Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Orrelius (1570) to the “paint”-clogged maps of Jasper Johns, the map has exercised a fascination over the minds of artists. A cartography of uninhabitable places seems to be developing – complete with decoy diagrams, abstract grid systems made of stone and tape (Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt), and electronic “mosaic” photomaps from NASA. Gallery floors are being turned into collections of parallels and meridians. Andre in a show in the Spring of ’67 at Dwan Gallery in California covered an entire floor with a “map” that people walked on – rectangular sunken “islands” were arranged in a regular order. Maps are becoming immense, heavy quadrangles, topographic limits that are emblems of perpetuity, interminable grid coordinates without Equators and Tropic Zones.

Lewis Carroll refers to this kind of abstract cartography in his The Hunting of the Snark (where a map contains “nothing”) and in Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (where a map contains “everything”). The Bellman’s map in the Snark reminds one of Jo Baer’s paintings.

He had bought a large map representing the sea,

Without least vestige of land:

And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be

A map they could all understand.

Jo Baer’s surfaces are certainly in keeping with the Captain’s map which is not a “void,” but “A perfect and absolute blank!” The opposite is the case, with the map in Carroll’s Sylvie. In Chapter 11, a German Professor tells how his country’s cartographers experimented with larger and larger maps until they finally made one with a scale of a mile to a mile. One could very well see the Professor’s explanation as a parable on the fate of painting since the 50s. The Professor said, “It has never been spread out, yet. The farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So now we use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”

The Bound Sphere Minus Lune by Ruth Vollmer may be seen as a globe with a cut away Northern region. Three arcs in the shape of crescents intersect at the “bound” equator. The “lune” triangulation in this orb detaches itself and becomes secondary “sculpture.”

There are approximately 50 Panama Canals to a cubic mile and there are 317 MILLION cubic miles of ocean.

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Nine Chains to the Moon

R. Buckminster Fuller has developed a type of writing and original cartography, that not only is pragmatic and practical but also astonishing and teratological. His Dymaxion Projection and World Energy Map is a Cosmographia that proves Ptolemy’s remark that, “no one presents it rightly unless he is an artist.” Each dot in the World Energy Map refers to “I% of World’s harnessed energy slave population (inanimate power serving man) in terms of human equivalents,” says Fuller. The use Fuller makes of the “dot” is in a sense a concentration or dilation of an infinite expanse of spheres of energy. The “dot” has its rim and middle, and could be related to Reinhardt’s mandala, Judd’s “device” of the specific and general, or Pascal’s universe of center and circumference.

Yet, the dot evades our capacity to find its center. Where is the central point, axis, pole dominant interest, fixed position, absolute structure, or decided goal? The mind is always being hurled towards the outer edge into intractable trajectories that lead to vertigo.

- 1 Recently drama critic Michael Fried has been enveloped by this “literal” abyss. (See “Objecthood and Art,” ArtForum, June 1967.

Smithson, Robert. "A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art." Art International (March 1968).