“The Last Nonsite”: Nonsite, Site Uncertain, Politics, and Prehistory

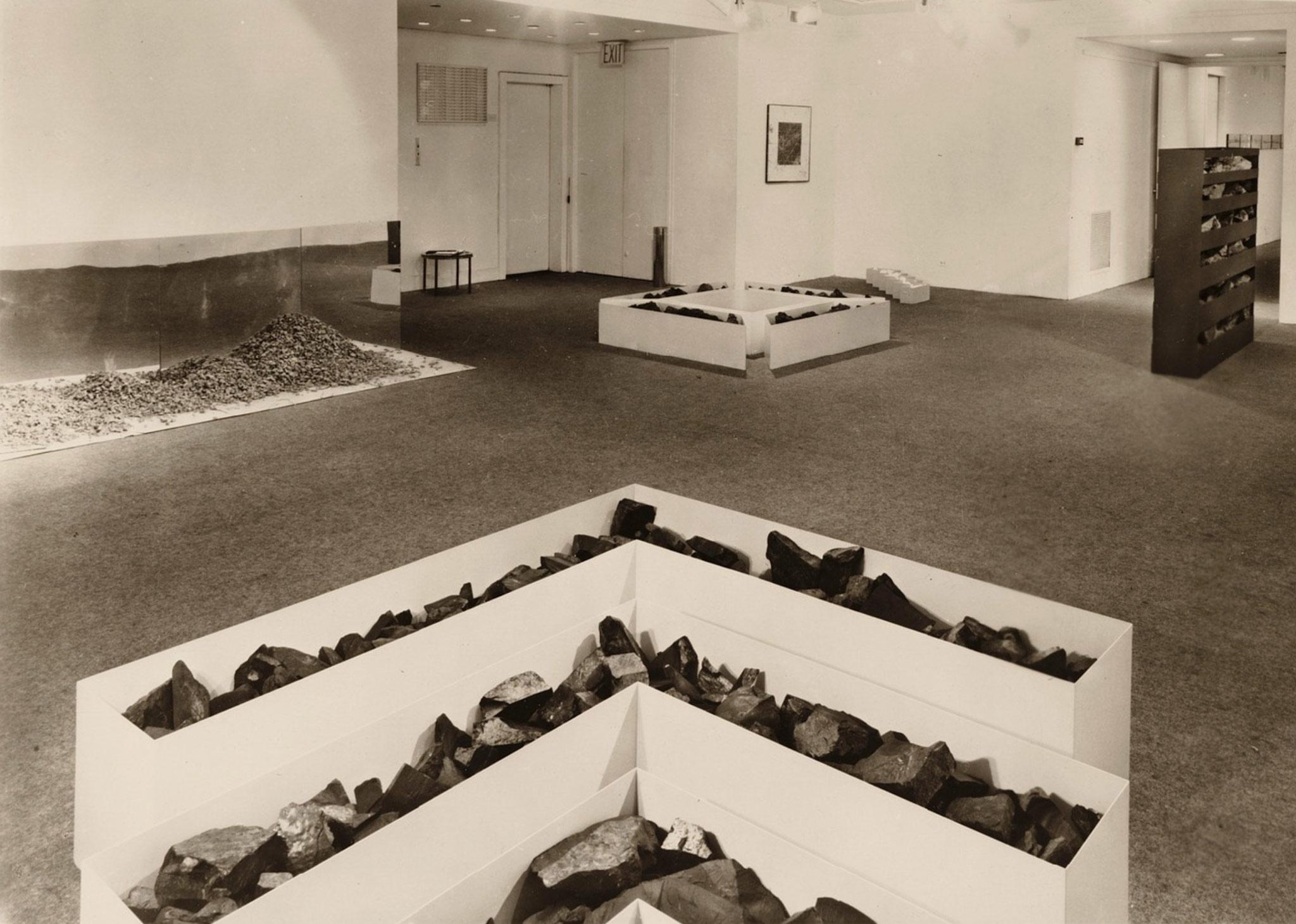

“Instead of putting something in the landscape I decided it would be interesting to transfer the land indoors, to the Nonsite,” Robert Smithson explained during the Earth Art Symposium at Cornell University in February 1969.1 He had recently completed Cayuga Salt Mine Project for the Earth Art exhibition at Cornell (“one of the most complex manifestations of Smithson’s Site/Nonsite dialectic,” Marin Sullivan has written) and an exhibition of his Nonsites had opened that month at the Dwan Gallery in New York City. The Nonsites are bin-like structures designed for gallery spaces—“rooms within rooms,” Smithson once said—containing materials collected on the artist’s perambulations, along with photographs and maps.2 Most Nonsites are named for the sites they abstract—Nonsite “Line of Wreckage,” Bayonne, New Jersey denotes the source of chunks of broken concrete, while Mono Lake Nonsite (Cinders Near Black Point) identifies the origin of volcanic cinders. “The site is a place you can visit and it involves travel as an aspect,” Smithson explained.3 Yet one Nonsite is an exception: Nonsite, Site Uncertain (1968) does not point to a specific geographic locale. If not a place one can visit, what site is abstracted by Nonsite, Site Uncertain and the coal that it contains?

Nonsite, Site Uncertain is comprised of seven beige-enameled, L-shaped steel bins arranged by scale, staggered to form a chevron pattern. As Smithson told Vancouver art historian Dennis Wheeler in 1970, if the bins of Nonsite, Site Uncertain were pushed together, “they would form a square without a central square…a sense of the incomplete/complete is present so that the containment isn’t quite contained.”4 Though the dialectical logic of the Nonsite does not have a named geographic site in the case of Nonsite, Site Uncertain, the missing center is hinted at by the medium of coal. Coal, fossilized vegetation from the Carboniferous Period, is categorically distinct from the geological materials of Smithson’s other Nonsites, such as slag or gypsum. Smithson was specific about the type of coal chosen for Nonsite, Site Uncertain. “Cannel coal” is found in “southern Ohio, and Kentucky,” he told Wheeler, explaining that he had read about it in a handbook of rocks and minerals: “You can look that up and draw whatever you want.”5 (Wheeler’s notes from the conversation read: “draw inferences from material.”)6 As a particular variant of coal, cannel is most closely associated with home heating and illumination; it was familiar as “fireplace” coal in midcentury America, and it is thought that the name elides the word “candle.” Large beds of cannel coal are found in southern Ohio, as well as eastern Kentucky in the environs of Cannel City.7

Coal was the subject of intense debate in 1968, the year Smithson made Nonsite, Site Uncertain. In January of 1968, Life Magazine ran a feature on “the new earth-moving machines,” with aerial imagery of a surface coal mine glossed by the caption “strip miners in Kentucky are violently defacing the land and ruining lives.”8 This was one of many high profile media features in the late 1960s and early 1970s pairing aerial images of dizzyingly vast landscapes stripped by power shovels with close-up portraits of Appalachian poverty—families displaced by landslides, floods, and lost access to drinking water.9 Despite these calamities, the federal government urged abundant coal production, later to ease dependence on foreign oil throughout the energy crises of the 1970s.10 Appalachian coal was in demand to “fuel power plants that light the sprawling suburbs and the dying cores of American cities,” producing landscapes hostile to biological and economic vitality alike.11

Locating Nonsite, Site Uncertain in the Carboniferous, Smithson situated it within “the politics of prehistory” rather than the fraught contemporary social geography of “somewhere in the Ohio and Kentucky area.”12 Smithson had more to say on Nonsite, Site Uncertain and the matter of coal in an interview with Paul Cummings in 1972:

The last Nonsite actually is one that involves coal and there the site belongs to the Carboniferous Period, so it no longer exists; the site becomes completely buried again. There’s no topographical reference…The coal comes from somewhere in the Ohio and Kentucky area, but the site is uncertain. That was the last Nonsite; you know, that was the end of that. So I wasn't dealing with the land surfaces at the end.13

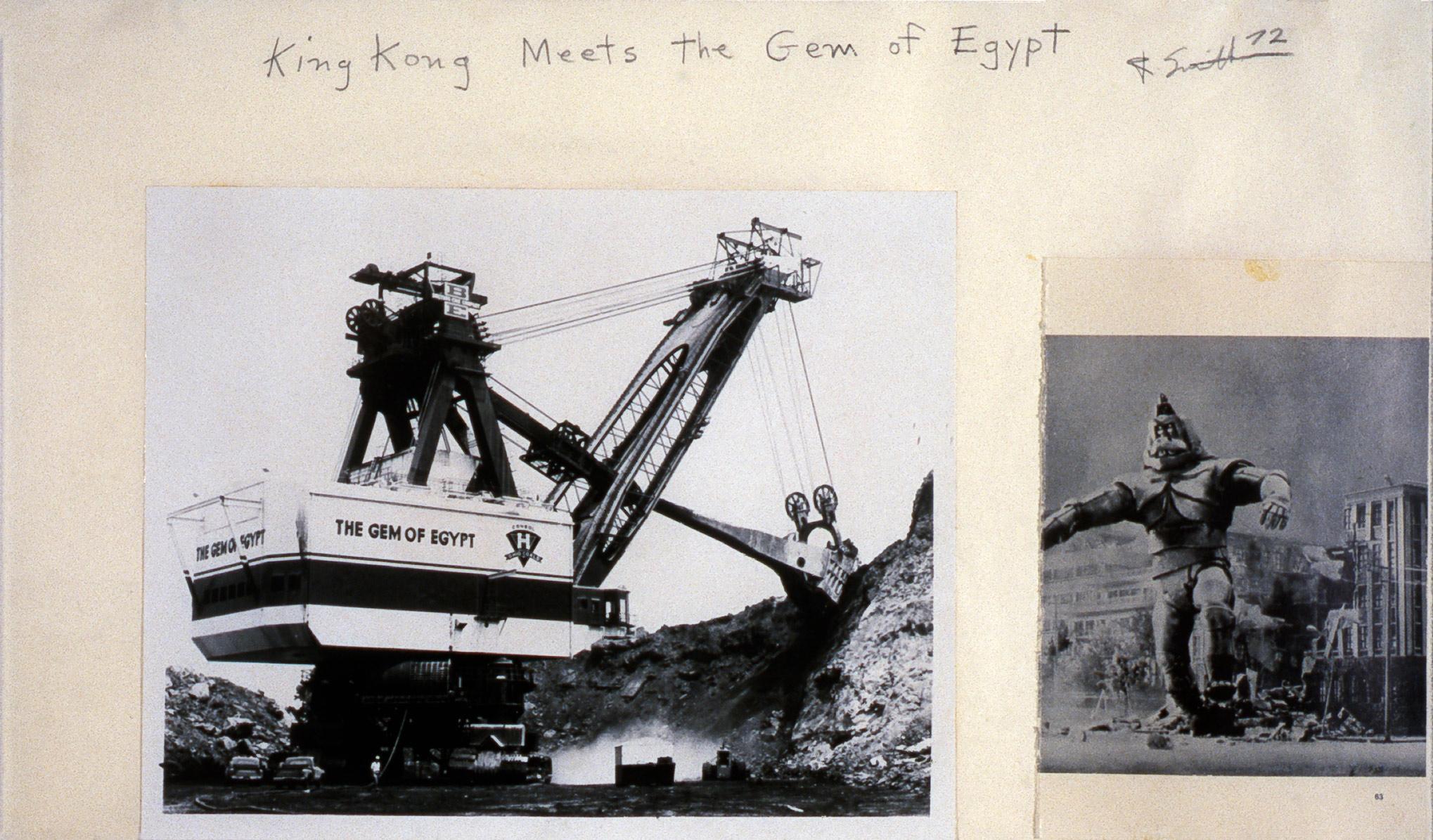

Nonsite, Site Uncertain was not actually the “last Nonsite” in a chronological sense, but it was something new: it pointed to sites of extraction at a moment when submerged Carboniferous matter was being uncovered with shocking efficiency by giant earth movers in the contested contemporary practice of strip mining. Though Nonsite, Site Uncertain references a “submerged” temporal site dating to the Carboniferous, Smithson could still point to “somewhere in the Ohio or Kentucky area” as the source of his cannel coal. This locale, specifically Egypt Valley in southeastern Ohio, had become a focus for Smithson by the 1970s. His collage King Kong and the GEM of Egypt (1972) likens the giant earth movers (GEMs) stripping the earth in Egypt Valley, Ohio, to King Kong ravaging Manhattan. He was closely attuned to the politics of environmentalism and mining— “a dialectic between ecologists and industrialists”— and understood the potential of earthworks as a form of land reclamation.14

By 1972, after completing his first permanent earthworks Spiral Jetty (1970) and Broken Circle/Spiral Hill (1971), Smithson actively sought to site earthworks on depleted coal mining sites. That year, he wrote a proposal for the reclamation of a strip mine in Egypt Valley, Ohio, arguing for the artist to address the fraught politics of coal mining: “The artist must accept and enter into all of the real problems that confront the ecologist and industrialist,” he wrote to the president of Hanna Coal.15 Smithson projected a grand vision for Ohio’s main coal mining region: “I know that I can make the Egypt Valley an important cultural asset to the whole world,” he promised.16 He might have been right, though this probably seemed preposterous to the mining industry that largely declined Smithson’s services. However, plans to redesign a devastated mining site in Creede, Colorado for the Minerals Engineering Company were underway at the time of his death in July, 1973. By then, Smithson had established that the next phase of his career would be dedicated to land reclamation and the development of public space.17 “What he wanted most, he never got—a chance to make a rehabilitative public art in these ‘disrupted areas’ on a truly grand scale, commensurate with the damage done by the industries,” wrote Lucy R. Lippard in 1980.18

Nonsite, Site Uncertain represents an inflection point as Smithson concluded his series of Nonsites, moving away from works conceived for gallery space to work directly in the landscape. The work was purchased shortly after its completion by the Vancouver architect Ian Davidson. In January 1970, Davidson commissioned Smithson to create Glass Strata with Mulch and Soil on the grounds of his home as Smithson waited to make Island of Broken Glass off the coast of Vancouver, a project that was never realized due to public outcry over potential injury to wildlife.19 Though Smithson made several subsequent Nonsites, Nonsite, Site Uncertain marked the end of the Nonsites— “that was the end of that”—and the beginning of deeper excavations in the landscape itself.

About the Author

Kirsten Swenson is a Massachusetts-based art historian and critic. She is currently writing a book entitled “Public Works: Land Art and Urban Redevelopment,” supported by a grant from the Graham Foundation and an American Council of Learned Societies Burkhardt Fellowship at the Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. She is the author of the books Irrational Judgments: Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt, and 1960s New York (Yale University Press, 2015) and, with Emily Eliza Scott, Critical Landscapes: Art, Space, Politics (University of California Press, 2015). Kirsten is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.

- 1Earth Art symposium transcript, Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Cornell University (February 6, 1969). Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 2, Folder 48. Referenced online: https://edan.si.edu/slideshow/viewer/?eadrefid=AAA.smitrobe_ref134

- 2“Fragments of an Interview with P.A. [Patsy] Norvell (1969,” in Jack Flam, ed. Robert Smithson: Collected Writings (Oakland: University of California Press, 1996) 192. First published in Lucy R. Lippard, Six Year: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966-1972.

- 3Earth Art symposium, ibid.

- 4Transcript of conversation between Robert Smithson and Dennis Wheeler at Sands Hotel, Side Two, page 2. Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://edan.si.edu/slideshow/viewer/?eadrefid=AAA.smitrobe_ref135

- 5Ibid.

- 6General correspondence, “Wheeler, Dennis,” Box 2, Folder 36. Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- 7Allan Sherman, et al. Facts about Coal (United States Department of the Interior, 1950).

- 8David Nevin, “These Murdered Old Mountains,” Life Magazine (Jan. 12 1968) 54. Photographs by Bob Gomel. View through Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=XkoEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA54&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

- 9Ibid. Photographs of Appalachian strip mines and displaced families, along with personal, pleading narratives were also the subject of Harry M. Claudel, My Land Is Dying (New York: Dutton, 1971), referenced by Robert Smithson in letters to strip mining executives as imagery to counteract with earth art reclamations.

- 10Increasing coal production was seen as a matter of national security during the Carter Administration. See President Jimmy Carter, Energy Address to the Nation, April 5, 1979. Loopholes in the Clean Air Act (1970) exempted existing coal-burning power plants and other industrial usages from regulation. See Richard Revesz and Jackie Lienke, Struggling for Air: Power Plants and the ‘War on Coal’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016) 3.

- 11James Branscome, “Appalachia: Like the Flayed Back of a Man,” New York Times Magazine (December 12, 1971).

- 12See Lucy R. Lippard, “Breaking Circles: The Politics of Prehistory,” in Robert Hobbs, Robert Smithson: Sculpture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981).

- 13Ibid.

- 14“Conversation with Robert Smithson (1972),” edited by Bruce Kurtz, in Flam, ibid. 265.

- 15Smithson, “Proposal (1972)” in Flam, ibid. 379-380.

- 16Robert Smithson, letter to Mr. Ralph Hatch, President, Hanna Coal Company (June 10, 1972). Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Box 5, Folder 29, “Proposed Mining Reclamation Projects Correspondence, 1972-1973.”

- 17According to Suzaan Boettger, Smithson had sent out fifty proposals to mining industries by the time of his death in 1973. Suzaan Boettger, Earthworks: Art and Landscape of the Sixties (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003) 232.

- 18Lippard, ibid. 40.

- 19Flam, ibid. 197. Also see Leah Modigliani, “Myth and the ‘home culture’ concept,” in Engendering an Avant-Garde: The Unsettled Landscapes of Vancouver Photo-Conceptualism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018).

Swenson, Kirsten. "'The Last Nonsite': Nonsite, Site Uncertain, Politics, and Prehistory." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 5 (October 2023). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/last-nonsite-nonsite-site-uncertain-politics-and-prehistory