Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan

Of the Mayan ideas on the forms of the earth we know little. The Aztec thought the crest of the earth was the top of a huge saurian monster, a kind of crocodile, which was the object of a certain cult. It is probable that Mayan had a similar belief, but it is not impossible that at the same time they considered the world to consist of seven compartments, perhaps stepped as four layers.

—J. Eric S. Thompson, Maya Hieroglyphic Writing

The characteristic feature of the savage mind is its timelessness: its object is to grasp the world as both a synchronic and a diachronic totality and the knowledge which it draws therefrom is like that afforded of a room by mirrors fixed on opposite walls, which reflect each other (as well as objects in the intervening space) although without being strictly parallel.

—Claude Levi-Strauss, The Savage Mind

Driving away from Merida down Highway 261 one becomes aware of the indifferent horizon. Quite apathetically it rests on the ground devouring everything that looks like something. One is always crossing the horizon, yet it always remains distant. In this line where sky meets earth, objects cease to exist. Since the car was at all times on some leftover horizon, one might say that the car was imprisoned in a line, a line that is in no way linear. The distance seemed to put restrictions on all forward movement, thus bringing the car to a countless series of standstills. How could one advance on the horizon, if it was already present under the wheels? A horizon is something else other than a horizon; it is closedness in openness, it is an enchanted region where down is up. Space can be approached, but time is far away. Time is devoid of objects when one displaces all destinations. The car kept going on the same horizon.

Looking down on the map (it was all there), a tangled network of horizon lines on paper called “roads,” some red, some black. Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Campeche, Tabasco, Chiapas and Guatemala congealed into a mass of gaps, points, and little blue threads (called rivers). The map legend contained signs in a neat row: archeological monuments (black), colonial monuments (black), historical site (black), bathing resort (blue), spa (red), hunting (green), fishing (blue), arts and crafts (green), aquatic sports (blue), national park (green), service station (yellow). On the map of Mexico they were scattered like the droppings of some small animal.

The Tourist Guide and Directory of Yucatan-Campeche rested on the car seat. On its cover was a crude drawing depicting the Spaniards meeting the Mayans, in the background was the temple of Chichén ltzá. On the top left-hand corner was printed “ ‘UY U TAN A KIN PECH’ (listen how they talk)—EXCLAIMED THE MAYANS ON HEARING THE SPANISH LANGUAGE,” and in the bottom left-hand corner “ ‘YUCATAN CAMPECHE’-REPEATED THE SPANIARDS WHEN THEY HEARD THESE WORDS.” A caption under all this said “Mayan and Spanish First Meeting 1517.” In the “Official Guide” to Uxmal, Fig. 28 shows 27 little drawings of “Pottery Found at Uxmal.” The shading on each pot consists of countless dots. Interest in such pots began to wane. The steady hiss of the air-conditioner in the rented Dodge Dart might have been the voice of Eecath—the god of thought and wind. Wayward thoughts blew around the car, wind blew over the scrub bushes outside. On the cover of Victor W. Von Hagen’s paperback World of the Maya it said, “A history that grew out of the jungles and wastelands of Central America.” In the rear-view mirror appeared Tezcatlipoca-demiurge of the “smoking-mirror.” “All those guide books are of no use,” said Tezcatlipoca, “You must travel at random, like the first Mayans, you risk getting lost in the thickets, but that is the only way to make art.”

Through the windshield the road stabbed the horizon, causing it to bleed a sunny incandescence. One couldn’t help feeling that this was a ride on a knife covered with solar blood. As it cut into the horizon a disruption took place. The tranquil drive became a sacrifice of matter that led to a discontinuous state of being, a world of quiet delirium. Just sitting there brought one into the wound of a terrestrial victim. This peaceful war between the elements is ever present in Mexico—an echo, perhaps, of the Aztec and Mayan human sacrifices.

The First Mirror Displacement:

Somewhere between Uman and Muna is a charred site. The people in this region clear land by burning it out. On this field of ashes (called by the natives a “milpa”) twelve mirrors were cantilevered into low mounds of red soil. Each mirror was twelve inches square, and supported from above and below by the scorched earth alone. The distribution of the squares followed the irregular contours on the ground, and they were placed in a random parallel direction. Bits of earth spilled onto the surfaces, thus sabotaging the perfect reflections of the sky. Dirt hung in the sultry sky. Bits of blazing cloud mixed with the ashy mass. The displacement was in the ground, not on it. Burnt tree stumps spread around the mirrors and vanished into the arid jungles.

The Second Mirror Displacement:

In a suburb of Uxmal, which is to say nowhere, the second displacement was deployed. What appeared to be a shallow quarry was dug into the ground to a depth of about four to five feet, exposing a bright red clay mixed with white limestone fragments. Near a small cliff the twelve mirrors were stuck into clods of earth. It was photographed from the top of the cliff. Again Tezcatlipoca spoke, “That camera is a portable tomb, you must remember that.” On this same site, the Great Ice Cap of Gondwanaland was constructed according to a map-outline on page 459 of Marshall Kay’s and Edwin H. Colbert’s Stratigraphy and Life History, It was an “earthmap” made of white limestone. A bit of the Carboniferous period is now installed near Uxmal. That great age of calcium carbonate seemed a fitting offering for a land so rich in limestone. Reconstructing a landmass that existed 350 to 305 million years ago on a terrain once controlled by sundry Mayan gods caused a collision in time that left one with a sense of the timeless.

Timelessness is found in the lapsed moments of perception, in the common pause that breaks apart into a sandstorm of pauses. The malady of wanting to “make” is unmade, and the malady of wanting to be “able” is disabled. Gondwanaland is a kind of memory, yet it is not a memory, it is but an incognito land mass that has been unthought about and turned into a Map of Impasse. You cannot visit Gondwanaland, but you can visit a “map” of it.

The Third Mirror Displacement:

The road went through butterfly swarms. Near Bolonchen de Rejon thousands of yellow, white and black swallowtail butterflies flew past the car in erratic, jerky flight patterns. Several smashed into the car radio aerial and were suspended on it because of the wind pressure. In the side of a heap of crushed limestone the twelve mirrors were cantilevered in the midst of large clusters of butterflies that had landed on the limestone. For brief moments flying butterflies were reflected; they seemed to fly through a sky of gravel. Shadows cast by the mirrors contrasted with those seconds of color. A scale in terms of “time” rather than “space” took place. The mirror itself is not subject to duration, because it is an ongoing abstraction that is always available and timeless. The reflections, on the other hand, are fleeting instances that evade measure. Space is the remains, or corpse, of time, it has dimensions. “Objects” are “sham space,” the excrement of thought and language. Once you start seeing objects in a positive or negative way you are on the road to derangement. Objects are phantoms of the mind, as false as angels. Itzpaplotl is the Mayan Obsidian Butterfly: “. . . a demonic goddess of unpredictable fate represented as beautiful but with death symbols on her face.” (See The Gods of Mexico by C. A. Burland.) This relates to the “black obsidian mirrorv used by Tezcatlipoca into which he gazed to see the future. “Unpredictable fate” seemed to guide the butterflies over the mirror displacements. This also brings to mind the concave mirrors of the Olmecs found at la Venta, Tabasco State, and researched by Robert Heizer, the archeologist. “The mirrors were masterpieces. Each had been so perfectly ground that when we rotated it the reflection we caught was never distorted in the least. Yet the hematite was so tough that we could not even scratch it with knives of hard Swedish steel. Such mirrors doubtless served equally well to adorn important personages or to kindle ritual fires.” (Gifts for the Jaguar God by Philip Drucker and Robert F. Heizer, N.G.M., 9/56.) “The Jaguar in the mirror that smokes in the World of the Elements knows the work of Carl Andre,” said Tezcatlipoca and Itzpaplotl at the same time in the same voice. “He knows the Future travels backwards,” they continued. Then they both vanished into the pavement of Highway 261.

The Fourth Mirror Displacement:

South of Campeche, on the way to Champoton, mirrors were set on the beach of the Gulf of Mexico. Jade colored water splashed near the mirrors, which were supported by dry seaweed and eroded rocks, but the reflections abolished the supports, and now words abolish the

reflections. The unnameable tonalities of blue that were once square tide pools of sky have vanished into the camera, and now rest in the cemetery of the printed page—Ancora in Arcadia morte. A sense of arrested breakdown prevails over the level mirror surfaces and the unlevel ground. “The true fiction eradicates the false reality,” said the voiceless voice of Chalchihiuticue—the Surd of the Sea. The mirror displacement cannot be expressed in rational dimensions. The distances between the twelve mirrors are shadowed disconnections, where measure is dropped and incomputable. Such mirror surfaces cannot be understood by reason. Who can divulge from what part of the sky the blue color came? Who can say how long the color lasted? Must “blue” mean something? Why do the mirrors display a conspiracy of muteness concerning their very existence? When does a displacement become a misplacement? These are forbidding questions that place comprehension in a predicament. The questions the mirrors ask always fall short of the answers. Mirrors thrive on surds, and generate incapacity. Reflections fall onto the mirrors without logic, and in so doing invalidate every rational assertion. Inexpressible limits are on the other side of the incidents, and they will never be grasped.

The Fifth Mirror Displacement:

At Palenque the lush jungle begins. The palisade, Stone Houses, Fortified Houses, Capital of the People of the Snake or City of Snakes are the names this region has been called. Writing about mirrors brings one into a groundless jungle where words bun; incessantly instead of insects. Here in the heat of reason (nobody knows what that is), one tends to remember and think in lumps. What really makes one listless is ill-founded enthusiasm, say the zeal for “pure color.” If colors can be pure and innocent, can they not also be impure and guilty? In the jungle all light is paralyzed. Particles of color infected the molten reflections on the twelve mirrors, and in so doing, engendered mixtures of darkness and light. Color as an agent of matter filled the reflected illuminations with shadowy tones, pressing the light into dusty material opacity. Flames of light were imprisoned in a jumbled spectrum of greens. Refracting sparks of sunshine seemed smothered under the weight of clouded mixtures—yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. The word “color” means at its origin to “cover” or “hide.” Matter eats up light and “covers” it with a confusion of color luminous lines emanate from the edges of the mirrors, yet the surface reflections manifest nothing but shady greens. Deadly greens that devour light. Acrylic and Day-glo are nothing to these raw states of light and color. Real color is risky, not like the tame stuff that comes out of tubes. We all know that there could never be anything like a “color-pathos” or a pathology of color. How could “yellow is yellow” survive as a malarial tautology? Who in their right mind would ever come up with a concept of perceptual petit mal? Nobody could ever believe that certain shades of green are carriers of chromatic fever. The notion that light is suffering from a color-sickness is both repugnant and absurd. That color is worse than eternity is an affront to enlightened criticism. Everybody knows that “pathetic” colors don’t exist. Yet, it is that very lack of “existence” that is so deep, profound and terrible. There is.no chromatic scale down there because all colors are present spawning agglutinations out of agglutinations. It is the incoherent mass that breeds color and kills light. The poised mirrors seemed to buckle slightly over the uncertain ground. Disjointed square streaks and smudges hovered close to incomprehensible shadows. Proportion was disconnected and in a condition of suspense. The double allure of the ground and the mirrors brought forth apparitions. Out of green reflections came the networks of Coatlicue, known to the Mayans as the Serpent lady: Mother Earth. Twistings and windings were frozen in the mirrors. On the outskirts of the ruins of Palenque or in the skirts of Coatlicue, rocks were overturned; first the rock was photographed, then the pit that remained. “Under each rock is an orgy of scale,” said Coatlicue, while flashing a green snake from a nearby “killer tree” (parasite vines that smother a tree, till they become the tree). Each pit contained miniature earthworks—tracks and traces of insects and other sundry small creatures. In some beetle dung, cobwebs, and nameless slime. In others cocoons, tiny ant nests and raw roots. If an artist could see the world through the eyes of a caterpillar he might be able to make some fascinating art. Each one of these secret dens was also the entrance to the abyss. Dungeons that dropped away from the eyes into a damp cosmos of fungus and mold—an exhibition of clammy solitude.

The Colloquy of Coatlicue and Cbronos

“You don’t have to have cows to be a cowboy.”

—Nudie

Coatlicue: You have no future.

Chronos: And you have no past.

Coatlicue: That doesn’t leave us much of a present.

Chronos: Maybe we are doomed to being merely some “light-years” with missing tenses.

Coatlicue: Or two inefficient memories.

Chronos: So this is Palenque.

Coatlicue: Yes; as soon as it was named it ceased to exist.

Chronos: Do you think those overturned rocks exist?

Coatlicue: They exist in the same way that undiscovered moons orbiting an unknown planet

exist.

Chronos: How can we talk about what exists, when we hardly exist ourselves?

Coatlicue: You don’t have to have existence to exist.

The Sixth Mirror Displacement:

From Ruinas Bonampak to Agua Azul in a single engine airplane with a broken window. Below, the jungle extinguished the ground, and spread the horizon into a smoldering periphery. This perimeter was subject to a double perception by which, on one hand, all escaped to the outside, and on the other, all collapsed inside; no boundaries could hold this jungle together. A dual catastrophe engulfed one “like a point,” yet the airplane continued as though nothing had happened. The eyes were circumscribed by a widening circle of vertiginous foliage, alldimensions at that edge were uprooted and flung outward into green blurs and blue haze. Butone just continued smoking and laughing. The match boxes in Mexico are odd, they are “things in themselves.” While one enjoys a cigarette, he can look at his yellow box of “Clasicos-De Lujo-La Central.” The match company has thoughtfully put a reproduction of Venus De Milo on the front cover, and a changing array of “fine art” on the back cover, such as Pedro Brueghel’s The Blind Leading the Blind. The sea of leaves below continued to exfoliate and infoliate; it thickened to a great degree. Out of the smoke of a Salem came the voice of Ometecuhtli—the Dual Being, but one could not hear what he had to say because the airplane engine roared too loudly. Down in the lagoons and swamps one could see infinite, isotropic, three-dimensional and homogeneous space sinking out of sight. Up and down the plane glided, over the inundating colors in the circular jungle. A fugitive seizure of “clear-air turbulence” tossed the plane about and caused mild nausea. The jungle grows only by means of its own negation—art does the same. Inexorably the circle tightened its coils as the plane gyrated over the landing strip. The immense horizon contracted its endless rings. Lower and lower into the vortex of Agua Azul, into the calm infernal center, and into the flaming spiral of Xiuhtecuhtli. Once on the ground another match was struck—the dugouts on the Rio Usumacinta were waiting.

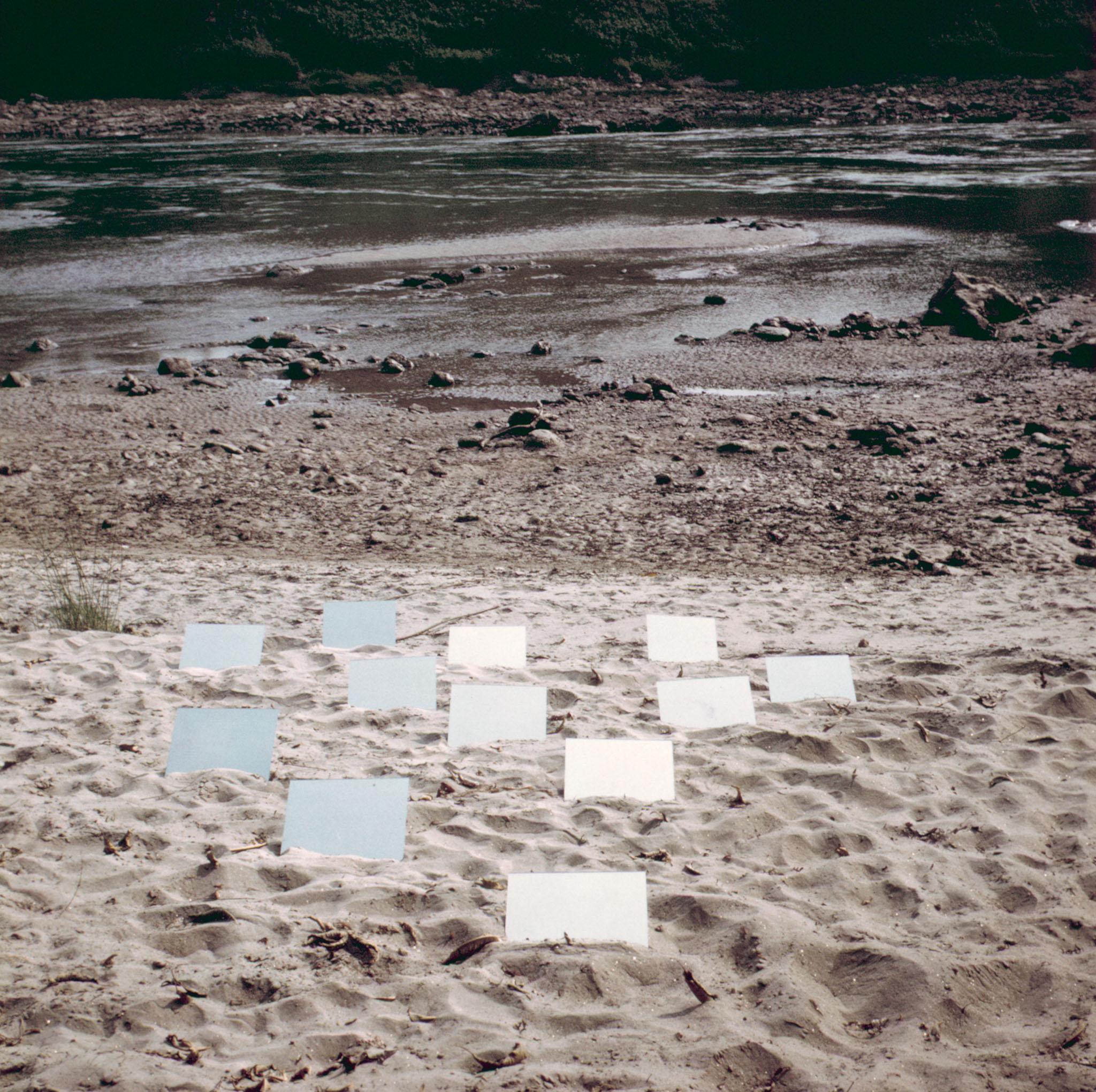

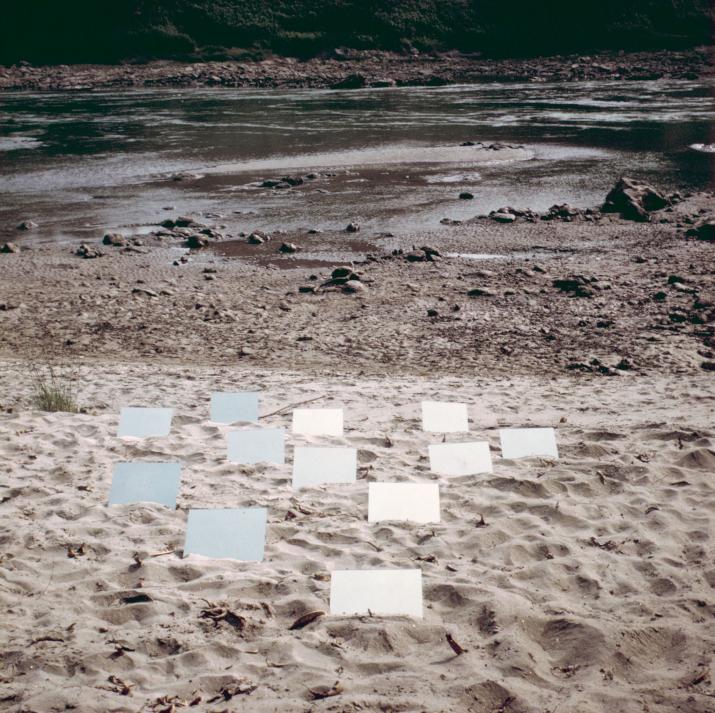

The current of the river carried one swiftly along. Perception was stunned by small whirlpools suddenly bubbling up till they exhausted themselves into minor rapids. No isolated moment on the river, no fixed point, just flickering moments of tumid duration. Iguanas sunning themselves on the incessant shores. Hyperbole touched the bottom of the literal. An excess of green sunk any upward movement. Today, we are afflicted with an inversion of hyperbole— gravity. Rivers of lead. Lakes of Asphalt. Heavy water. Generalized mud. The Caretaker of Dullness—habit—lurks everywhere. Tlazolteotl: Eater of Filth rules. Near a pile of rubble in the river, by what was once one of the Temples of Yaxchilan, the dugout stopped. On a high sandbank the mirrors were placed.

The Seventh Mirror Displacement:

Yaxchilan may not be wasted (or, as good as waste. doomed to wasting) but still building itself out of secrets and shadows. On a multifarious confusion of ruins are frail huts made of sticks with thatched roofs. The world of the Maya and its cosmography has been deformed and beaten down by the pressure of years. The natives at Yaxchilan are weary because of that long yesterday, that unending calamitous day. They might even be disappointed by the grand nullity of their own past attainments. Shattered recesses with wild growths of creepers and weeds disclosed a broken geometry. Turning the pages of a book on Mayan temples, one is relieved of the futile and stupefying mazes of the tropical density. The load of actual, on-the-spot perception is drained away into banal appreciation. The ghostly photographic remains are sapped memories, a mock reality of decomposition. Pigs run around the tottering masses, and so do tourists. Horizons were submerged and suffocated in an asphyxiation of vanishing points. Archeologists had tried to transport a large stone stele out of the region by floating it on dugouts up the Usumacinta to Agua Azul, but they couldn’t get it into an airplane, so they had to take it back to Yaxchilan. There it remains today, collecting moss—a monument to Sisyphus. Near this stele, the mirrors were balanced in a tentacled tree. A giant vegetable squid inverted in the ground. Sunrays filtered into the reflections. The displacement addressed itself to a teeming frontality that made the tree into a jumbled wall full of snarls and tangles. The mirror surfaces being disconnected from each other “destructuralized” any literal logic. Up and down parallels were dislocated into twelve centers of gravity.

A precarious balance existed somewhere between the tree and the dead leaves. The gravity lost itself in a web of possibilities; as one looked more and more possibilities emerged because nothing was certain. Nine of the twelve mirrors in the photograph are plainly visible, two have sunk into shadow. One on the lower right is all but eclipsed. The displacement is divided into five rows. On the site the rows would come and go as the light fell. Countless chromatic patches were wrecked on the mirrors, flakes of sunshine dispersed over the reflecting surfaces and obliterated the square edges, leaving indistinct pulverizations of color on an indeterminate grid. A mirror on the third row jammed between two branches flashed into dematerialization. Other mirrors escaped into visual extinguishment. Bits of reflected jungle retreated from one’s perception. Each point of focus spilled into cavities of foliage. Glutinous light submerged vision under a wilderness of unassimilated seeing. Scraps of sight accumulated until the eyes were engulfed by scrambled reflections. What was seen reeled off into indecisive zones. The eyes seemed to look. Were they looking? Perhaps. Other eyes were looking. A Mexican gave the displacement a long, imploring gaze. Even if you cannot look, others will look for you. Art brings sight to a halt, but that halt has a way of unravelling itself. All the reflections expired into the thickets of Yaxchilan. One must remember that writing on art replaces presence by absence by substituting the abstraction of language for the real thing. There was a friction between the mirrors and the tree, now there is a friction between language and memory. A memory of reflections becomes an absence of absences. On this site the third upside-down tree was planted. The first is in Alfred, New York State, the second is in Captiva Island, Florida; lines drawn on a map will connect them. Are they totems of rootlessness that relate to one another? Do they mark a dizzy path from one doubtful point to another? Is this a mode of travel that does not in the least try to establish a coherent coming and going between the here and the there? Perhaps they are dislocated “North and South poles” marking peripheral places, polar regions of the mind fixed in mundane matter—poles that have slipped from the geographical moorings of the world’s axis. Central points that evade being central. Are they dead roots that haplessly hang off inverted trunks in a vast “no man’s land” that drifts toward vacancy? In the riddling zones, nothing is for sure. Nevertheless, flies are attracted to such riddles. Flies would come and go from all over to look at the upside-down trees, and peer at them with their compound eyes. What the fly sees is “something a little worse than a newspaper photograph as it would look to us under a magnifying glass.” (See Animals Without Backbones, Ralph Buchsbaum) The “trees” are dedicated to the flies. Dragonflies, fruit flies, horseflies. They are all welcome to walk on the roots with their sticky, padded feet, in order to get a close look. Why should flies be without art?

The Eighth Mirror Displacement:

Against the current of the Usumacinta the dugout headed for the Island of Blue Waters. The island annihilates itself in the presence of the river, both in fact and mind. Small bits of sediment dropped away from the sand flats into the river. Small bits of perception dropped away from the edges of eyesight. Where is the island? The unknowable zero island. Were the mirrors mounted on something that was dropping, draining, eroding, trickling, spilling away? Sight turned away from its own looking. Particles of matter slowly crumbled down the slope that held the mirrors. Tinges, stains, tints, and tones crumbled into the eyes. The eyes became two wastebaskets filled with diverse colors, variegations, ashy hues, blotches and sunburned chromatics. To reconstruct what the eyes see in words, in an “ideal language” is a vain exploit. Why not reconstruct one’s inability to see? Let us give passing shape to the unconsolidated views that surround a work of art, and develop a type of “anti-vision” or negative seeing. The river shored up clay, loess, and similar matter, that shored up the slope, that shored up the mirrors. The mind shored up thoughts and memories, that shored up points of view, that shored up the swaying glances of the eyes. Sight consisted of knotted reflections bouncing off and on the mirrors and the eyes. Every clear view slipped into its own abstract slump. All viewpoints choked and died on the tepidity of the tropical air. The eyes, being infected by all kinds of nameless tropisms, couldn’t see straight. Vision sagged, caved in, and broke apart. Trying to look at the mirrors took the shape of a game of pool under water. All the clear ideas of what had been done melted into perceptual puddles, causing the brain to gurgle thoughts. Walking conditioned sight, and sight conditioned walking, till it seemed only the feet could see. Squinting helped somewhat, yet that didn’t keep views from tumbling over each other. The oblique angles of the mirrors disclosed an altitude so remote that bits of “place” were cast into a white sky. How could that section of visibility be put together again? Perhaps the eyes should have been screwed up into a sharper focus. But no, the focus was at times cock-eyed, at times myopic, overexposed, or cracked. Oh, for the happy days of pure walls and pure floors!

Flatness was nowhere to be found. Walls of collapsed mud, and floors of bleached detritus replaced the flatness of rooms. The eyes crawled over grains, chips, and other jungle obstructions. From the blind side reflections studded the shore—into an anti-vision. Outside this island are other islands of incommensurable dimension. For example, the Land of Mu, built on “shaky ground” by Ignatius Donnelly in his book Atlantis, the Antediluvian World, 1882, based on an imaginative translation of Mayan script by Diego de Landa.1

The Ninth Mirror Displacement:

Some “enantiomorphic” travel through Villahermosa, Frontera, Cd. del Carmen, past the Laguna de Terminos. Two asymmetrical trails that mirror each other could be called enantiomorphic after those two common enantiomorphs—the right and left hands. Eyes are enantiomorphs. Writing the reflection is supposed to match the physical reality, yet somehow the enantiomorphs don’t quite fit together. The right hand is always at variance with the left. Villahermosa on the map is an irregular yellow shape with a star in it. Villahermosa on the earth is an irregular yellow shape with no star in it. Frontera and Cd. del Carmen are white circles with black rings around them. Frontera and Cd. del Carmen on the earth are white circles with no black rings around them. You say nobody was looking when they passed through those cities. You may be right, but then you may be wrong. You are caught in your own enantiomorph. The double aspect of Quetzalcoatl is less a person than an operation of totemic perception. Quetzalcoatl becomes one half of an enantiomorph (coati means twin) in search of the other half. A mirror looking for its reflection but never quite finding it. The morning star of Quetzal is apt to be polarized in the shadowy reflection of the evening star. The journeys of Quetzalcoatl are recorded in Sahagun’s Historia Universal de las Cosasde Nueva Espana, parts of which are translated into English in The Gods of Mexico by C. A. Burland. In Sahagun’s Book III, Chapter XIII, “Which, tells of the departure of Quetzalcoatl towards Tlapallan (the place of many colours) and of the things he performed on the way thither.” Quetzalcoatl rested near a great tree (Quanhtitlan). Quetzalcoatl looked into his “obsidian mirror” and said “Now I become aged.” “The name of that place has ever afterwards been Ucuetlatitlan (Beside the Tree of Old Age). Suddenly he seized stones from the path and threw them against the unlucky tree. For many years thereafter the stones remained encrusted in the ancient tree.” By traveling with Quetzalcoatl one becomes aware of primordial time or final time—The Tree of Rocks. (A memo for a possible “earthwork”—balance slabs of rock in tree limbs.) But if one wishes to be ingenious enough to erase time one requires mirrors, not rocks. A strange thing, this branching mode of travel: one perceives in every past moment a parting of ways, a highway spreads into a bifurcating and trifurcating region of zigzags. Near Sabancuy the last displacement in the cycle was done. In mangrove (also called mangrave) branches and roots mirrors were suspended. There will be those who will say “that’s getting close to nature.” But what is meant by such “nature” is anything but natural. When the conscious artist perceives “nature” everywhere he starts detecting falsity in the apparent thickets, in the appearance of the real, and in the end he is skeptical about all notions of existence, objects, reality, etc. Art works out of the inexplicable. Contrary to affirmations of nature, art is inclined to semblances and masks, it flourishes on discrepancy. It sustains itself not on differentiation, but dedifferentiation, not on creation but decreation, not on nature but denaturalization, etc. Judgments and opinions in the area of art are doubtful murmurs in mental mud. Only appearances are fertile; they are gateways to the primordial. Every artist owes his existence to such mirages. The ponderous illusions of solidity, the non-existence of things, is what the artist takes for “materials.” It is this absence of mailer that weighs so heavy on him, causing him to invoke gravity. Actual delirium is devoid of insanity; if insanity existed it would break the spell of productive apathy. Artists are not motivated by a need to communicate; travel over the unfathomable is the only condition.

Living beings dwell in their expectations rather than in their senses. If they are ever to see what they see, they must first in a manner stop living; they must suspend the will, as Schopenhauer put it; they must photograph the idea that is flying past, veiled in its very swiftness. —George Santayana, Scepticism and Animal Faith

If you visit the sites (a doubtful probability) you find nothing but memory-traces, for the mirror displacements were dismantled right after they were photographed. The mirrors are somewhere in New York. The reflected light has been erased. Remembrances are but numbers on a map, vacant memories constellating the intangible terrains in deleted vicinities. It is, the dimension of absence that remains to be found. The expunged color that remains to be seen. The fictive voices of the totems have exhausted their arguments. Yucatan is elsewhere.

- 1 This is just one of thousands of hypothetical arguments in favor of Atlantis. Conjectural maps that point to this non-existent site fill many unread atlases, It very well could be that the Maya writings that, alluded to “the Old Serpent covered with green feathers, who lies in the Ocean” was Quetzalcoatl or the Sargasso Sea: Every wayward geographer of Atlantis has his own curious theory, they never seem 10 be alike. From Plato’s Timaeus to Codex Vaticanus A the documents of the lost island proliferate. On a site in Loveladies, Long Beach Island. New Jersey a map of tons of clear broken glass will follow Mr. Scott-Elliot’s map of Atlantis. Other Maps of Broken Glass (Atlantis) will follow, each with its own odd limits. Outside in the open air the glass map under the cycles of the sun radiates brightness without electric technology. Light is separable from color and form. It is a shimmering collapse of decreated sharpness, poised on broken points showing the degrees of reflected incandescence. Color is the diminution of light. The cracked transparency of the glass heaps diffuses the daylight of the actual solar source—nothing is fused or connected. The light of exploding magma on the sun is cast on to Atlantis, and ends in a cold luminosity. The heat of the solar rays collides with the spheres of gases that enclose the Earth. Like the glass, the rays are shattered, broken bits of energy, no stronger than moonbeams. A luciferous incest of light particles flashes into a brittle mass. A stagnant blaze sinks into the glassy map of a nonexistent island. The sheets of glass leaning against each other allow the sunny flickers to slide down into hidden fractures of splintered shadow. The map is a series of “upheavals” and “collapses”—a strata of unstable fragments is arrested by the friction of stability. The memory of what is not may be better than the amnesia of what is.

Smithson, Robert. "Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan." Artforum, Vol. 8, no. 1, (September 1969).