Haunted: Robert Smithson’s "My House is a Decayed House," 1962

“History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors.” If the sardonic analogy sounds like Robert Smithson, you’re close: it was written by his favorite poet, T.S. Eliot. The line could apply to the aged Renaissance and Baroque architecture jumbled on a dusky hillside that Smithson depicted in a gouache, ink and collage painting on paper in 1962. But to name it he took another assertion from that poem by Eliot, Gerontion: “My house is a decayed house.” Visually rich, given that enigmatic title—no residence is seen—yet rarely exhibited and never before analyzed, My House Is a Decayed House encapsulates Smithson’s artistic approach and personal concerns from late 1961-63 that radiate into his later work.

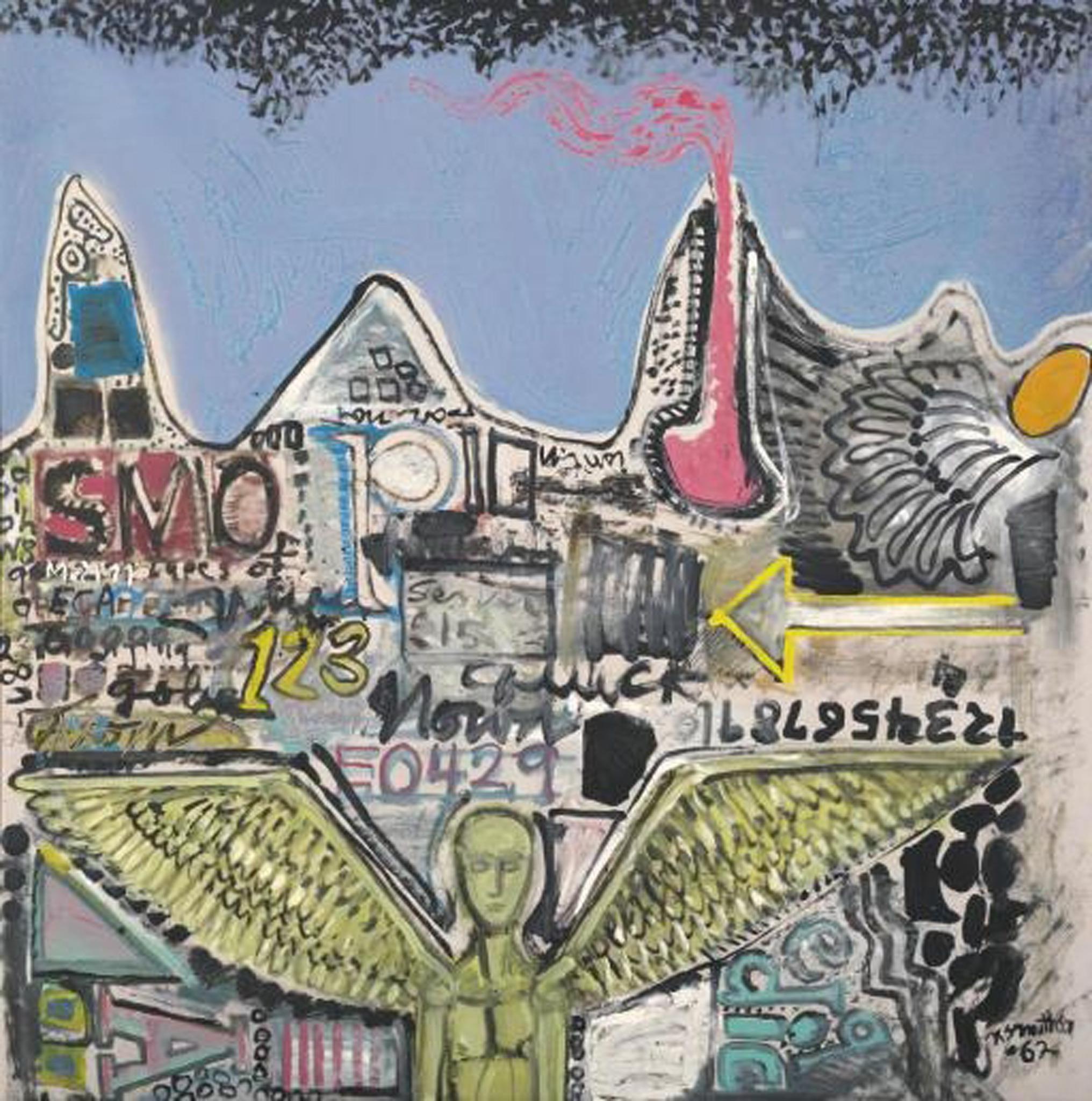

From the gloomy blue-gray-black terrain rising to about three-quarters of the paper’s twenty-four-inch height, three dark towers jut into a violet sky, its opacity and their skewed angles signaling something awry. Horizontal striations call up terraces and steps around the facade of a domed Baroque church with decorative flourishes. Pictures of architectural and statuary fragments cut from book illustrations and embedded within paint and overlaid with marking, reflect the popularity of collage following the previous fall’s international survey The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Repeated hatch marks and obscure arches and rectangles within the shadowy scene invoke Piranesi’s etchings of imaginary prisons. The view exaggerates what Smithson would have experienced the previous summer when in Rome for his show at Galleria George Lester.

[More illustrations and details are at the bottom of the page].

Eliot “had a big influence on me, of course, after going to Rome” Smithson later recalled, referring to his Catholic affiliation and “wrestling” with Eliot’s “Anglo-Catholicism.”1 More directly, he had tussled with Lester’s reluctance to exhibit his pictures of Christ’s Passion, pleading “Don’t be afraid of the word ‘religion’.”2 Now, several months later, Christ’s image has disappeared in favor of a house of worship’s façade. As Rome is the seat of the Vatican, My House is a Decayed House could be taken as a Roman Catholic’s critique of the Church. But ambivalently so, as it was exhibited in Smithson’s March 1962 solo show at the Richard Castellane Gallery, Manhattan, “Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings for Lent,” opening a week after Ash Wednesday.

My House is a Decayed House also links Smithson’s affiliation with deteriorated architecture. At 17 he drew a dilapidated fence before a multi-story construction site, Untitled (Ruined Building) (1955). In 1970, drawings pictured building fragments mired in mounds of earth; that year the trajectory of architectural ruination culminated in his dumping an avalanche of dirt atop the roof of Kent State University’s grounds storage cabin until its main beam cracked, creating Partially Buried Woodshed.

But Smithson’s adoption of Eliot’s plaint made the degradation intimate. “Gerontion” is Greek for "little old man" (English: “gerontology”); “My house is a decayed house” comes between two declarations that “I am an old man.” Eliot’s allusion to the body is affirmed by an analysis of Gerontion in Smithson’s book collection by the Eliot expert George Williamson, “The final separated lines [Tenants of the house, / Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season] again collapse man and house. . . Thus ‘house’ and ‘head’ present the physical and mental aspects of one comprehensive symbol.”3 At twenty-two he would seem to be too young to identify with the “old man in a dry month” narrating the poem, but then when Gerontion was published in 1920 Eliot was only a decade older, thirty-two. Both lamented losses; the year of My House is a Decayed House Smithson wrote of “unknown devastations” and “A terrible yearning for Innocence stares back over Original Sin into some impossible paradise.”4

In the painting, to the left of the church’s tall double doors is a collaged photograph of a small squat building. It is a lower portion of a photograph of a 14th century landmark in Prague, House of the Golden Well, made in the late 1930s by Czech photographer Karel Plicka.5 Smithson’s cropping of Plicka’s image to focus on its current occupant “Jos. Sucky Drogerie” emphasizes its identity as a drugstore. With its association with illness, and its upper reliefs of patron saints thought to protect from the plague, Smithson accentuated Eliot’s metaphor that the decay is not architectural but corporeal. That is what he had experienced in the “house of Smithson”: a year and a half earlier his paternal grandmother Lillian Smithson had died at seventy-seven; her son Harold had been lost at sea when a Merchant Marine during World War II in 1943 at thirty-six, when his nephew Smithson was five. Concurrent with this painting, Smithson’s partner Nancy Holt’s mother Louise Holt was suffering from cancer (she would succumb in April).

But Smithson’s choice of a Czech reference to illness specifically relates it to his own mother Susan’s family, the Dukes, who were “of middle European of diverse origins, I suppose mainly Slavic.”6 (At the time that would have been the state of Czechoslovakia, whose capital was Prague.) Susan had lost her father Alexander when she was eight months, her mother Mary when she was seventeen, and her older sister Julia, who had lived with the Smithsons since around the time of Smithson’s birth and with whom he was close, the previous year.7 Most intimately, Susan’s and his father Irving’s firstborn, Harold, had died at almost nine-and-a-half of leukemia, then an untreatable horrifically hemorrhaging death. Less than two years later the joyous birth of their successor only child Smithson was shadowed by premature and mortifying deaths.

The year after painting My House is a Decayed House Smithson collaged a printed female eye and below it wrote in cursive the word “tear,” the pair repeated across the page as if endlessly weeping into a reddened ground. That elegy, Untitled (Tear) could apply to all of them, as the nexus of references to loss also reflects Smithson’s own sensitivities. Among the incantations—verses merging poetry, chant, and prayer—he wrote in 1961, some herald angels, suffering: To the Blind Angel; To the Dead Angel: “To this martyred Ghost . . .Blessed be the dead angel/For he is our Life;” and To the Flayed Angels: “There is the angel of God burning with blood.”8 Likewise, angels have alighted throughout his My House is a Decayed House; one atop the church’s dome prominently clasps a cross as would a martyr.9 Both the painting and the incantations literalize the idiom of consoling bereaved parents by speaking of a dead child as having become an angel in heaven; according to Luke 20:36, “Neither can they die any more: for they are equal to the angels, and are the children of God, being the children of the resurrection.”

Also in 1962, Smithson painted Buried Angel. The winged nude, developmentally between boyish and “built” (and who are numerous on the announcement of the Castellane Lenten show and in many drawings of the time), is underground midst another mishmash—rectangles, encrypted numbers and words, and scribbled marks. Yet this angel’s articulated pecs and taut wings indicate he is not at all dead. Unlike Eliot’s claim in Gerontion, “I have no ghosts,” Smithson’s hid in “cunning passages,” haunting.

Selected Bibliography

Anisfeld, Leon and A. D. Richards. "The replacement child, variations on a theme in history and psychoanalysis." Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 55 (2000): 301-318.

Eliot, T. S. The Complete Poems and Plays 1909-1950. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962

Flam, Jack. Robert Smithson, The Collected Writings, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Fraiberg, S., E. Adelson, and V. Shapiro. "Ghosts in the Nursery: A Psychoanalytic Approach to the Problem of Impaired Infant-Mother Relationship." Journal of American Academy of Child Psychiatry 14 (1975): 387-421.

Plicka, Karel. City of Baroque and Gothic. London, Lincolns-Prager 1946.

Smithson, Robert. Letters to George B. Lester [microfilm], 1960-1963. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. reel 5438.

Tsai, Eugenie. Robert Smithson: Unearthed, Drawings Collages, Writings. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Williamson, George. A Reader's Guide to T. S. Eliot: A Poem-by-Poem Analysis. New York: Noonday Press, 1957.

About the Author

Suzaan Boettger is an art historian, critic and lecturer based in New York City, and Professor Emerita of the History of Art at Bergen Community College. A scholar of environmental and environmentalist art, she is the author of Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties (University of California Press, 2003) as well as contributions to over a dozen books and catalogues including the 2004 Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s Robert Smithson survey exhibition, as well as numerous articles and reviews.

With support from Henry Moore Foundation

Holt/Smithson Foundation's Scholarly Text Program has been funded in part through the generosity of the Henry Moore Foundation Grants Program.

- 1Jack Flam, ed., Robert Smithson, The Collected Writings, “Oral history interview with Robert Smithson, 1972" Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996, 282.

- 2Robert Smithson letter to George B. Lester, 1960-1963. May 17, 1961 Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. reel 5438, frame 1270.

- 3George Williamson, A Reader's Guide to T. S. Eliot: A Poem-by-Poem Analysis. New York: Noonday, 1957, 112. Smithson’s ownership of that standard guide to Eliot’s work indicates the seriousness of his own study of the poet. At his death he owned seven books by Eliot and six of literary criticism about his work, the most in his book collection regarding any poet.

- 4Robert Smithson, "The Iconography of Desolation (ca. 1962)," Flam, 320, 322.

- 5Through the Consortium of Art and Architectural Historians, scholar of Czech architecture Kimberly E. Zarecor identified Karel Plicka as the photographer, and connected me with David Muhlena, Library Director, Skala Bartizal Library, National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, who identified the image. Among the many books of Karel Plicka’s photographs of Prague in which this image appears published before 1962 is City of Baroque and Gothic, London, Lincolns-Prager 1946, 148.

- 6Flam, Oral History interview, 278.

- 7Chronologies for Smithson's exhibitions at the New York Cultural Center (1974) and Cornell University (1981) describe Susan's age at her mother's death as thirteen. The New Jersey Death Index recorded Mary Miller Duke's death as October 1925 when Susan was seventeen.

- 8Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Reel 3834, frames 186, 188, 238. Discussing the Smithsons’ loss of their first son, Holt also used the “ghost” metaphor, one that psychologists also apply, “And then there’s probably always the ghost of that other child around.” My conversation with Nancy Holt, January 22, 1996.

- 9Some of the sculptured angels he cut from book illustrations resemble Bernini's angels in billowing drapery on the Ponte Sant Angelo over the Tiber River.

Boettger, Suzaan. "Haunted: Robert Smithson’s 'My House is a Decayed House' 1962." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 2 (October 2020). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/haunted-robert-smithsons-my-house-decayed-house-1962.