Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport Project, 1966-67

There’s no hurry here, Doctor. This is a landscape without time.

– The Crystal World, J.G. Ballard (1966)1

I think you have to find a site that is free of scenic meaning… I prefer views that are expansive, that include everything…

— Robert Smithson (1972)2

Robert Smithson consulted with the engineering and architectural firm Tippetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton (TAMS) from 1966 to 1967 on the design of Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport (DFW). This opportunity was spurred by a panel discussion featuring Smithson titled “Shaping the Environment: The Artist and the City” at Yale University in 1966.3 Audience member Walther Prokosch, who worked at TAMS, appears to have seen an analog in Smithson’s ideas around “crystalline networks” to the firm's interest in modular design and, following the discussion, he invited Smithson as artist consultant.4 Smithson took on the project with zeal, producing a dossier of proposal material that envisioned extensive earthworks installed between runways.5 In addition, Smithson also planned for a gallery in the airport which would feature a multimedia exhibition of didactics, photography, films, and television feeds showcasing live footage of the outdoor projects.

TAMS would eventually lose the bid for the DFW airport and, in turn, none of the proposals Smithson suggested would be realized. However, Smithson would draw deeply from this experience, propelling him toward his iconic sculptures, whose foreshocks are evident in the work produced during this period. In the TAMS proposals one will find paths, portals, fringes, dialectics, bulldozers, and spirals to nowhere—all quintessential Smithson. The singular form of Smithson’s unrealized TAMS airport proposal exists through a network of interconnected drawings, writings, sculptures, models, and interviews. Today we can peruse these ideas, craning our minds to imagine what glimpses could have been waiting for us in the empty fields of the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport.

The advent of the Jumbo Jet and the construction of the US Interstate Highway System in the post-war era proved to be an epochal transformation in mass travel. These advances bore technical and pragmatic implications that asked for fresh architectural paradigms of airports. At the time, the construction of the Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport was the largest in the world in terms of land area. Even as a folksy New York Times article hailed the airport as the “biggest public‐works project since the pyramids,”6 Thomas M. Sullivan (Executive Director of the Regional Airport Authority) coolly countered this sentiment in the same article by stating “we’re not building a monument, we’re building a tool.”7 It would prove to be a fitting tension for the artist.

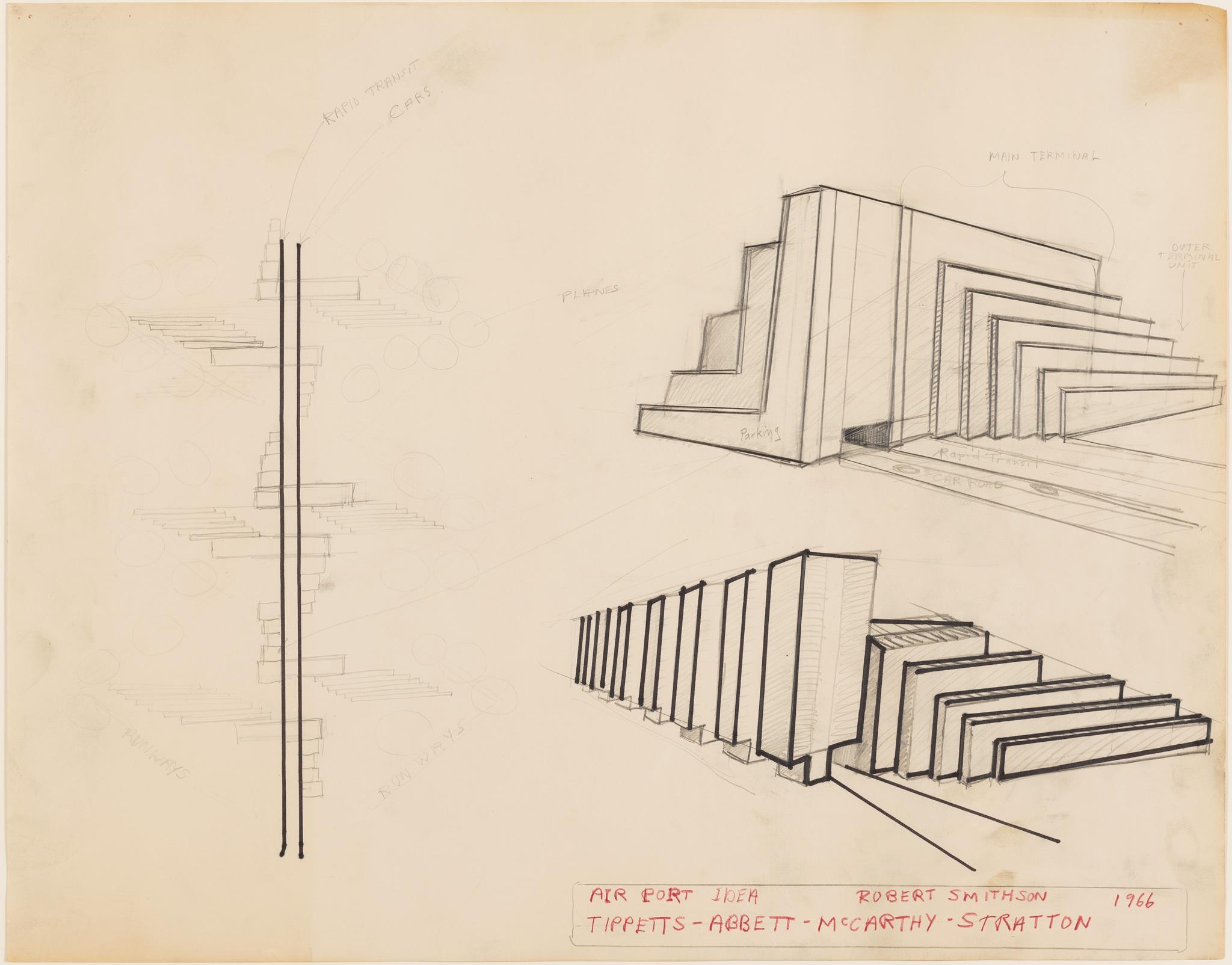

Early Smithson drawings and sculptures from his time as a consultant included architectural designs for the Dallas-Fort Worth airport terminals. These works, recalling ziggurats or temples with refracting and crystal-like motifs, seem to pay homage to both Minimalist sculpture and the science fiction narratives Smithson enjoyed and frequently referenced. However, as the TAMS project evolved, Smithson became less interested in the structures of the airport than he was in the periphery of the spaces the airport created. These “clear zones,'' as Smithson referred to them, were created by the 9 ½ miles of oblique runways, or “man-made geological networks of concrete”8 cutting through 17,500 acres of vacant pasture. This wholly “new landscape,”9 existed part and parcel to the infrastructure of jets, “between the center and the edge of things,”10 and was a place Smithson understood as terra nullius.

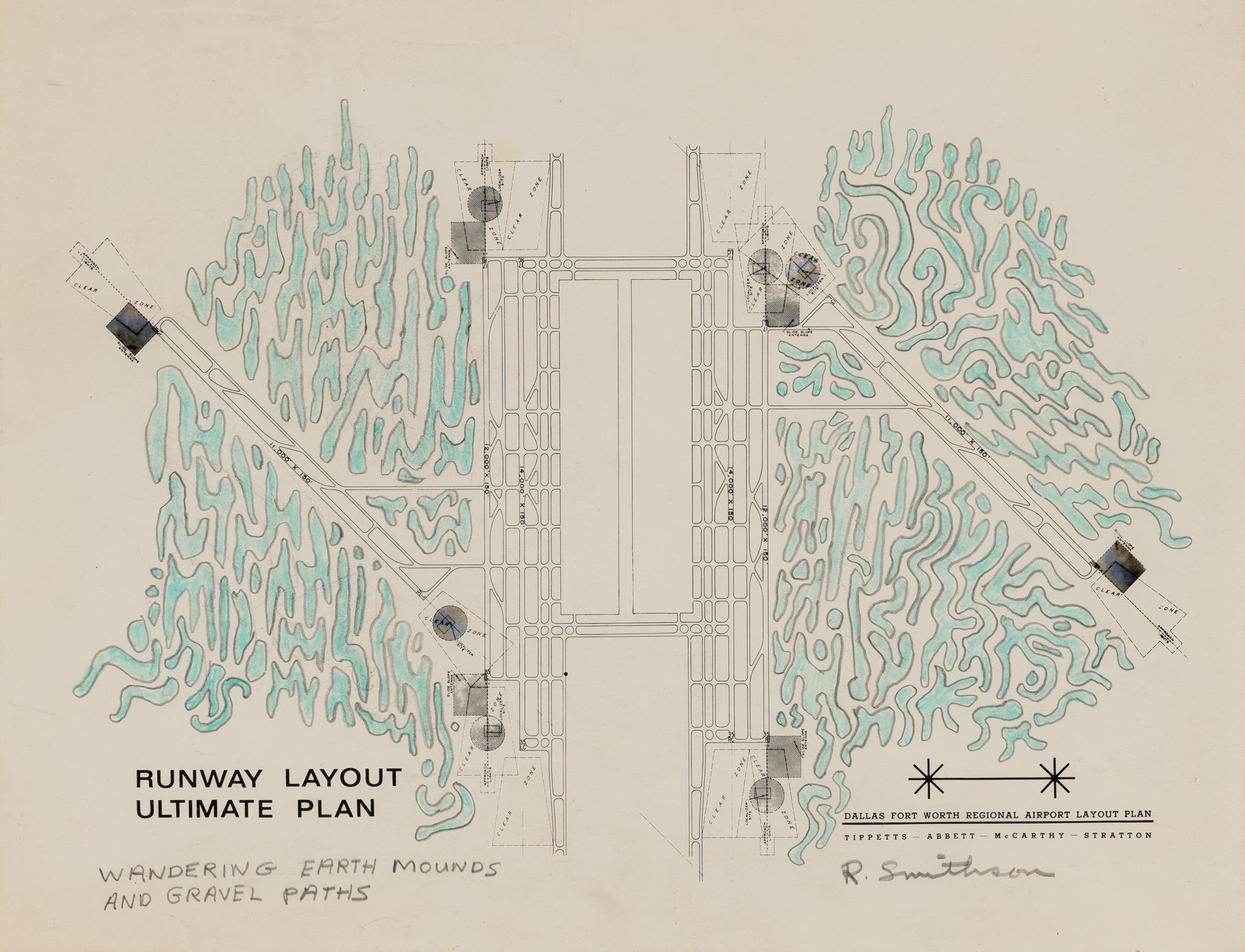

Smithson’s informal role at TAMS, which paid him roughly four hundred dollars a month,11 included site trips to North Texas, periodic meetings with Prokosch and other architects, and access to surveying and planning material. During this period, Smithson often communicated his ideas by drawing directly on provided maps. Drawings for these proposals tended to be economic in their execution and characterized by block text descriptions. On a runway layout plan, he drew a series of organic forms labeled “WANDERING EARTH MOUNDS AND GRAVEL PATHS” and another “A WEB OF WHITE GRAVEL (6’ WIDE) PATHS SURROUNDING WATER STORAGE TANKS.” The TAMS planning documents offered Smithson a bird's-eye view of the vast interstices between the airfield, terminals, and airport boundaries. This aerial perspective would become a catalyzing focus for what Smithson envisioned as large-scale interventions into the otherwise vacant landscapes whose total form could only be seen from above.12

The Photostat collage titled Aerial Map Proposal for Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport was included in his essay "Aerial Art," published in Studio International in 1969. The essay contained descriptions of a concrete spiral by Smithson, a mound work by Robert Morris, a buried cube by Sol LeWitt, and work comprising either a bomb crater or field of flowers13 by Carl Andre. Supergroup Smithson-LeWitt-Andre-Morris’s gestures seem to share a reference to the extractive and additive qualities of construction. These proposals point to the “preliminary aspects of building”14 and utilize the constituent parts of “pavements, holes, trenches, mounds, heaps” which, for Smithson, “have an esthetic potential.”15 In addition to referencing these “discrete stages”16 of airport construction—the mound and crater, inverted Towers of Babel17 and buried boxes—complement each other formally and provided for Smithson a “stasis within all this flux.”18

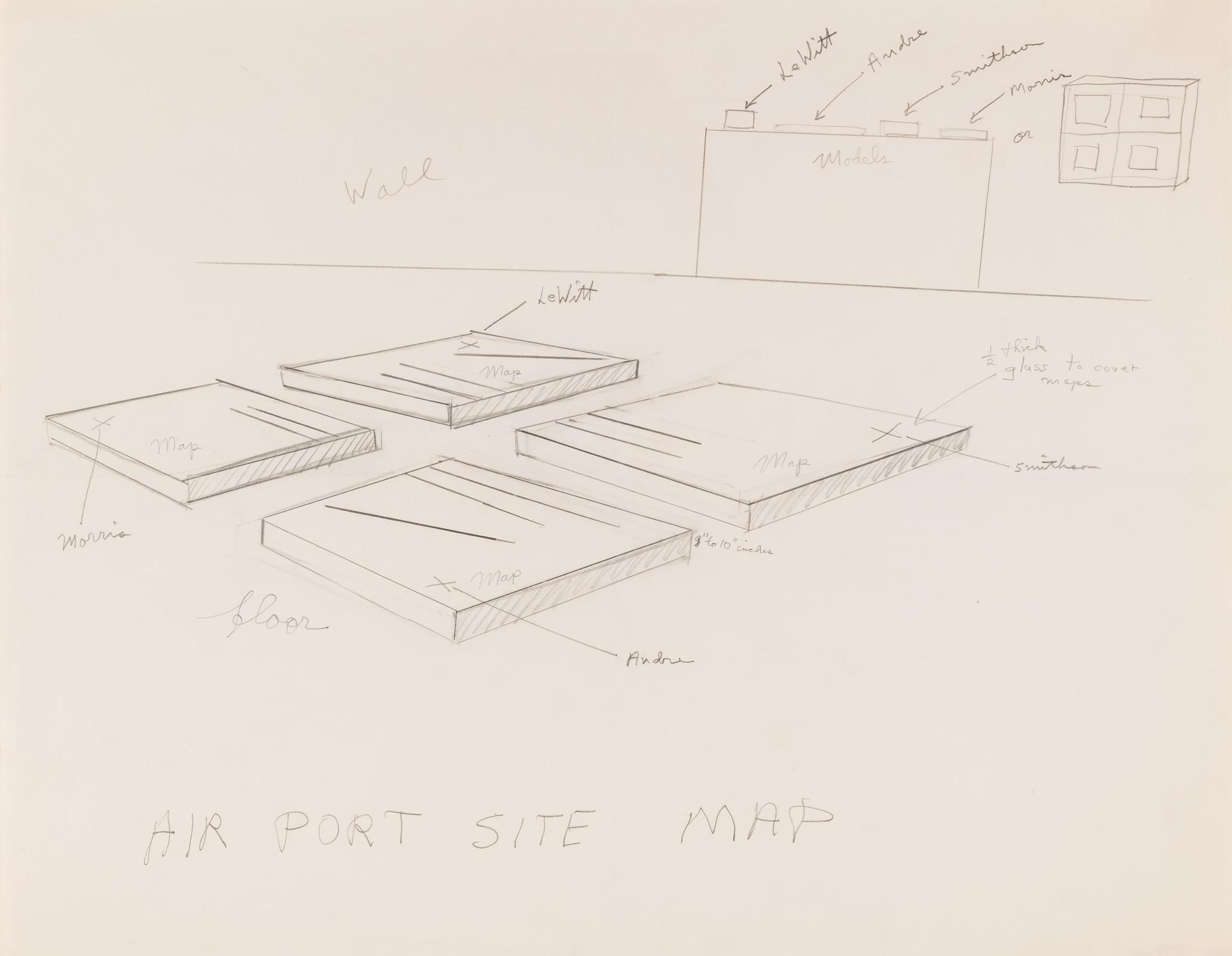

It is through these proposals in “Aerial Art” that Smithson recognized a necessity for a secondary exhibition space in the terminal as a “gallery” or “aerial museum.”19 In a drawing labeled “SITE MAP” Smithson planned an exhibition to explain scope and scale—with large maps encased in half-inch glass across the floor and scale models placed on pedestals. Smithson expands the possibilities of the exhibition design in “Aerial Art” to include diagrams, photographs, and films of the projects under construction. The remoteness of the “earthworks” presented a challenge between what was “out-there” and what could be communicated indoors. Central to Smithson’s proposal was a system of television cameras with live feeds of the works “transmitting these things back in.”20 It is important to highlight that this proposal for Smithson was the beginning of the Site/Nonsite dialectic and earthworks21 that would later define part of Smithson’s self-described “mature”22 period.

An airport, with its coming and going-ness in a place of mass solitude and similitude, has been characterized by Marc Auge as a “non-place.”23 It seems Smithson thought about the airport in similar terms: “All dimension seems to be lost in the process. In other words, you are really going from some place to some place, which is to say nowhere in particular.”24 Even the name “Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport” has a built-in nowhere-ness. The site of DFW was the product of years of negotiation for federal aviation funding between the two rival cities of Dallas and Fort Worth. City leaders eventually agreed on the fuzzy average between themselves and chose to position the airport on “30 square miles of empty ranching land”25 . The site, liminal in the extreme, ended up straddling both Dallas and Tarrant County while also simultaneously occupying the towns of Irving, Grapevine, Coppell, and Euless.26 As if to mark the airport’s collapse into non-place, a photograph from the four-day dedication of the airport features a young boy mounted on a pony standing in the pasture outside the airport as the iconic Concorde jet takes off behind him.27 Smithson wrote, “Those nondescript regions at the circumference of the project led me to the earth itself. What was to be ‘the biggest airport in the world’ became a speck in the Texas prairie.”28

The region of North Central Texas, which envelops DFW, spent most of the Cretaceous Period at the edge of a shallow sea. Ancient waters repeatedly rose, covered, and retreated—printing layers of limestone, marl, shale, and sand across the surface.29 For Smithson, the “Earth is a jumbled museum,”30 and it is clear he understood that the subsequent soil formed by these Upper Cretaceous rocks once supported the vast Blackland prairies that covered the region in full panorama31 before they were hollowed out from farming and development to precarious levels.32 As Smithson remarks in the conclusion of his essay Towards the Development of an Air Terminal Site, the artist “does not impose, but rather exposes the site.”33

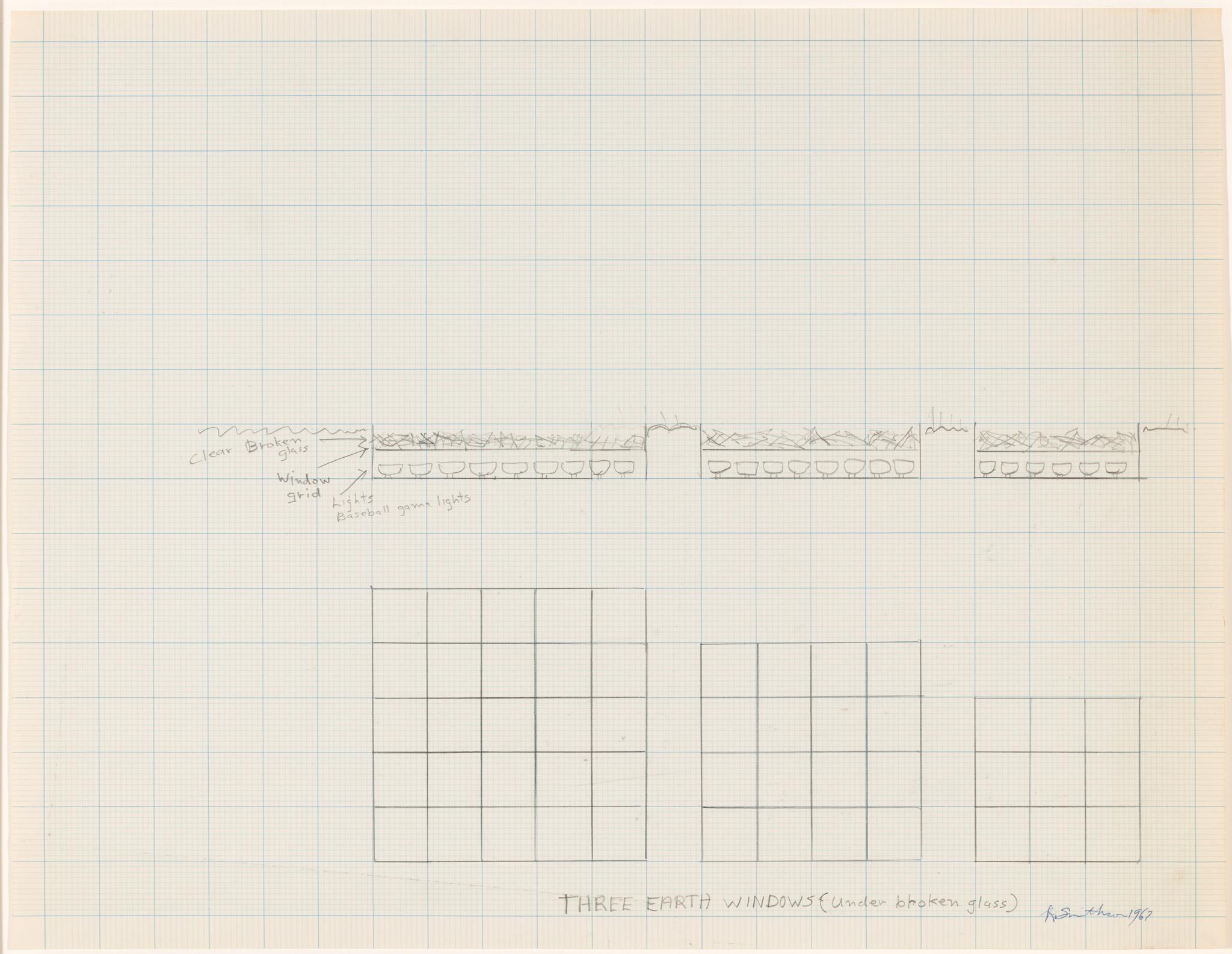

The proposal drawing, Three Earth Windows (Under Broken Glass), envisions a series of large-scale recessed squares cut into the ground, where rear-projected "baseball game lights" are directed upward through a horizontal grid and broken glass. In his essay Ultramodern, penned a year after his consultancy ended, Smithson intriguingly describes the "window" as a dual space, simultaneously open and closed, enigmatically observing that it “makes one aware of absolute inertia or the perfect instant, when time oscillates in a circumscribed place.”34 The drawing of Three Earth Windows conjures the image of gazing through an airplane porthole during the fleeting moments of arrival or departure. Here, the shimmering spectacle of lights illuminates a series of earth-time portals jittering between ground and sky, as well as between infrastructure and sculpture—a fitting sphinx for a nowhere prairie.

Selected Bibliography

Boettger, Suzaan. Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2002.

Flam, Jack, ed. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Lippard, Lucy R, ed. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

Piccardo, Emanuele and Amit Wolf, eds. Dialogues: Gianni Pettena and Robert Smithson In Beyond Environment. Barcelona: Actar Publishers, 2014.

Tsai, Eugenie with Cornelia Butler, eds. Robert Smithson. University of California Press, 2004.

About the Author

Trey Burns is an artist, writer, and educator currently working in the New Media department at the University of North Texas. Since 2018, he has been co-director of Sweet Pass Sculpture Park, a non-profit arts organization that provides space and support for experimental and large-scale outdoor works by emerging voices. In 2023 Sweet Pass received a Grants for Arts Projects award from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) for the alternative education and exhibition program Sculpture School, which invites artists to look more deeply at place.

- 1J.G. Ballard, The Crystal World, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), 10.

- 2Robert Smithson, “Dialogues: Gianni Pettena and Robert Smithson.” in Beyond Environment ed. Emanuele Piccardo & Amit Wolf (Actar Publishers, 2014), 70.

- 3To date, no recording of the talk has been located.

- 4Boettger, Suzann. Earthworks: Art and Landscape of the Sixties. (University of California Press, 2002), 52.

- 5At the time of the TAMS consultancy Smithson was referring to these works as “aerial art” and in a later interview clarifies “My first proposal was something called ‘aerial art’ which would be earthworks on the fringes of the airfield you would see from the air.” Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution (1972),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 291.

- 6Molly Ivins. “Texas Scale Airport.” New York Times, Sept 10, 1973.

- 7Ibid.

- 8This quote is from an article for Harper’s Bazaar written in 1966, the same year Smithson started his consultancy with TAMS. He is considering the highways in New Jersey suburbs as an artificial geographic feature. Robert Smithson. “The Crystal Land”, The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York University Press, 1979), 19.

- 9Robert Smithson, “Aerial Art,” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 116.

- 10“Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution (1972),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 296.

- 11RSNHP, microfilm reel, 3832, frames 902 and 906. Referenced in Robert Smithson ed. Eugenie Tsai with Cornelia Butler (University of California Press, 2004), 91.

- 12Smithson referred to earthworks in early writings as “aerial” art because for him it “connotes a certain kind of scale consciousness which I wanted to get across.” Robert Smithson, “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson (1969-1970),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 210.

- 13Andre’s proposal is titled “A crater formed by a one-ton bomb dropped from 10,000 feet. Or An acre of blue-bonnets (state flowers of Texas).”

- 14Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution (1972),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 291.

- 15Robert Smithson. “Towards the Development of an Air Terminal Site (1967),” The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York University Press, 1979), 44.

- 16Ibid.

- 17In a conversation with filmmaker Dennis Wheeler, Smithson explains that the spiral forms in his work are not “going up” but are more like “inversions of Tatlin’s Monument” or “the Tower of Babel.” Robert Smithson, “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson (1969-1970),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 200.

- 18In the parlance of airport planners, “clear zones”, also called “Runway Protection Zones,” are set aside at the end of runways as these locations have a high potential for accidents. This quotation is from an interview where Smithson is speaking about the proposed earthworks, and he refers to them as “disasters but the disasters are sort of frozen.” Ibid. 212.

- 19Robert Smithson, “Aerial Art,” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 116.

- 20Robert Smithson, “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson (1969-1970),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 212.

- 21Robert Smithson stated “I got interested in the earthworks as a result of that airport project. The Nonsites came as a result of my thinking about putting large-scale earthworks out on the edge on the airfield, and then I thought how can I transmit that into the center?” “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson (1969-1970),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 211-212.

- 22Smithson describes in an interview with Paul Cummings that “I would say that I began to function as a conscious artist around 1964-1965. I think I started doing works then that were mature.” Interview with Robert Smithson for the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution (1972),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 283.

- 23There are undeniable similarities between the literary device used in the prologue to Non-Places, as we follow Pierre DuPont to the airport, to Smithson’s 1966 essay The Crystal Land, where Smithson appears to have an almost psychedelic experience while driving around with Donald Judd, Julie Finch, and Nancy Holt looking at rocks. This relationship between Augé’s “non-place” and Smithson’s work coalesces around their exploration of our evolving relationship with the built world and the resulting landscapes' both charged and alienating qualities. Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (London: Verso, 1995).

- 24Robert Smithson, “Fragments of an Interview with P. A. Norvell, April, 1969,” in Six Years, ed. Lucy R. Lippard (University of California Press, 1997), 90.

- 25Ivins, Molly. “Texas Scale Airport.” New York Times, Sept 10, 1973.

- 26The North Texas Commission (NTC), reacting to the awkward conurbation of “Dallas-Fort Worth” that the airport created, went so far as to try and rebrand the region. “Metroplex”, a portmanteau of metropolis and complex, was adopted in 1973. Both shiny and generic, it was never widely embraced and was tacked on to create the chimera term “Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex” as the megalopolis is frequently referred to today. Still, others refer to the region by the International Air Transport Association's (IATA) Location Identifier: DFW. "Our History." North Texas Commission - DFW. Accessed [July 28, 2023]. https://www.ntc-dfw.org/history.

- 27Photograph taken September 20, 1973. According to emails between the author and the Media and Communications Department at DFW, while this is a popular photograph often used in promotional materials both the subject in the photograph and photographer are unknown. The Concorde jet made its first flight to the United States for the commemoration of DFW airport in 1973. The form of the Concorde resembles the “pyramidal slabs, and flying obelisks” that Smithson describes in his essay “Towards the Development of an Air Terminal Site (1967)” as part of the futuristic crystalline structures that he envisions for the future of air travel. Bernabo, By Marc. "Concorde Takes Bow." Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Texas), September 21, 1973: 1.

- 28

Robert Smithson, letter of 31 July 1970 to Rolf-Dieter Herrmann in Rolf-Dieter Herrmann, “In

Search of a Cosmological Dimension, Robert Smithson’s Dallas-Fort Worth Airport Project,” Arts Magazine 3 no. 9, May 1978, 111.

- 29Diggs, George M., Barney L. Lipscomb, and Robert J. O'Kennon. Illustrated Flora of North Central Texas. (Fort Worth, TX: Botanical Research Institute of Texas Press, 1999), 21.

- 30Smithson, Robert, “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,” The Writings of Robert Smithson ed. Nancy Holt (New York University Press, 1979), 89.

- 31An early settler to the North Texas region describes vast seas of prairie as a “boundless plain scarcely broken by a single slope or valley” (Smyth, 1852) Diggs, George M., Barney L. Lipscomb, and Robert J. O'Kennon. Illustrated Flora of North Central Texas. (Fort Worth, TX: Botanical Research Institute of Texas Press, 1999), 34.

- 32The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has stated that less than 1% of the original Blackland prairie remains.

- 33Robert Smithson. “Towards the Development of an Air Terminal Site (1967),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 60.

- 34Robert Smithson. “Ultramodern (1967),” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings ed. Jack Flam (University of California Press, 1996), 64.

Burns, Trey. "Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport Project, 1966-67." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 6 (January 2024). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/dallas-fort-worth-regional-airport-project-1966-67.