Britannia Beach Project

It was early in December 1969, while still in negotiations with the government of British Columbia over securing the Miami Islet site for his Island of Broken Glass proposal1 , when Smithson visited the Anaconda Copper Mine at Britannia Beach (just north of the city of Vancouver, British Columbia). What came out of that visit was a series of drawings that included Spill: Fluvial Discharge (Britannia Beach Project).

The artist’s time in Vancouver occurred during the heady, early days of the environmental movement. While pursued on many fronts, throughout the second half of the 1960s there was a persistent focus on the depletion of the earth’s resources, including an unsettling awareness of the entropic reality of the mining industry’s ever-accelerating extraction of the earth’s nonrenewable resources. In 1972, The Club of Rome sponsored and MIT published The Limits to Growth, a report forecasting the limits and dire consequences of the exponential growth in resource consumption which warned that the current trajectory was not sustainable.2 A thirty-year update of the original study offered one change, noting that humanity had already overshot the limits of the Earth’s resource capacity.3 A designated Earth’s Overshoot Day now marks the date each year when humanity’s depletion of the earth’s renewable raw resources in a given year exceeds the Earth’s regenerative capacity.4

From the beginning, the mining industry made a concerted effort to counter this discourse. Together with other extractionist industries they initiated a public relations drive intent on redirecting awareness away from the unsustainable extraction and resource depletion side of the debates. Regrettably, it was effective. By the early 70s, much of the public eco-discourse had shifted to reclamation and anti-pollution—remedial initiatives focused on managing the overburden and pollution side of the extracting industries.

Smithson was a player in all this, and it was during this time that the artist went through a similar shifting of focus. Along with spending less time in museum spaces, Smithson also moved away from the extraction of naturally-occurring solid material, which he had performed in his series of Nonsites in the late 60s, to a subsequent series of gravitational Pours in 1969-70. The Pours consisted of unconsolidated manufactured materials dumped down eroded slopes. As the poured material descended, they took on the geo-physical contours of the existing slope. While titled “pours” and not “spills”—a pour implies control, where as a spill connotes a lack of it—the series coyly mirrored industrial mishaps with the earth’s own process. What to make of that unresolved connection has been debated ever since.

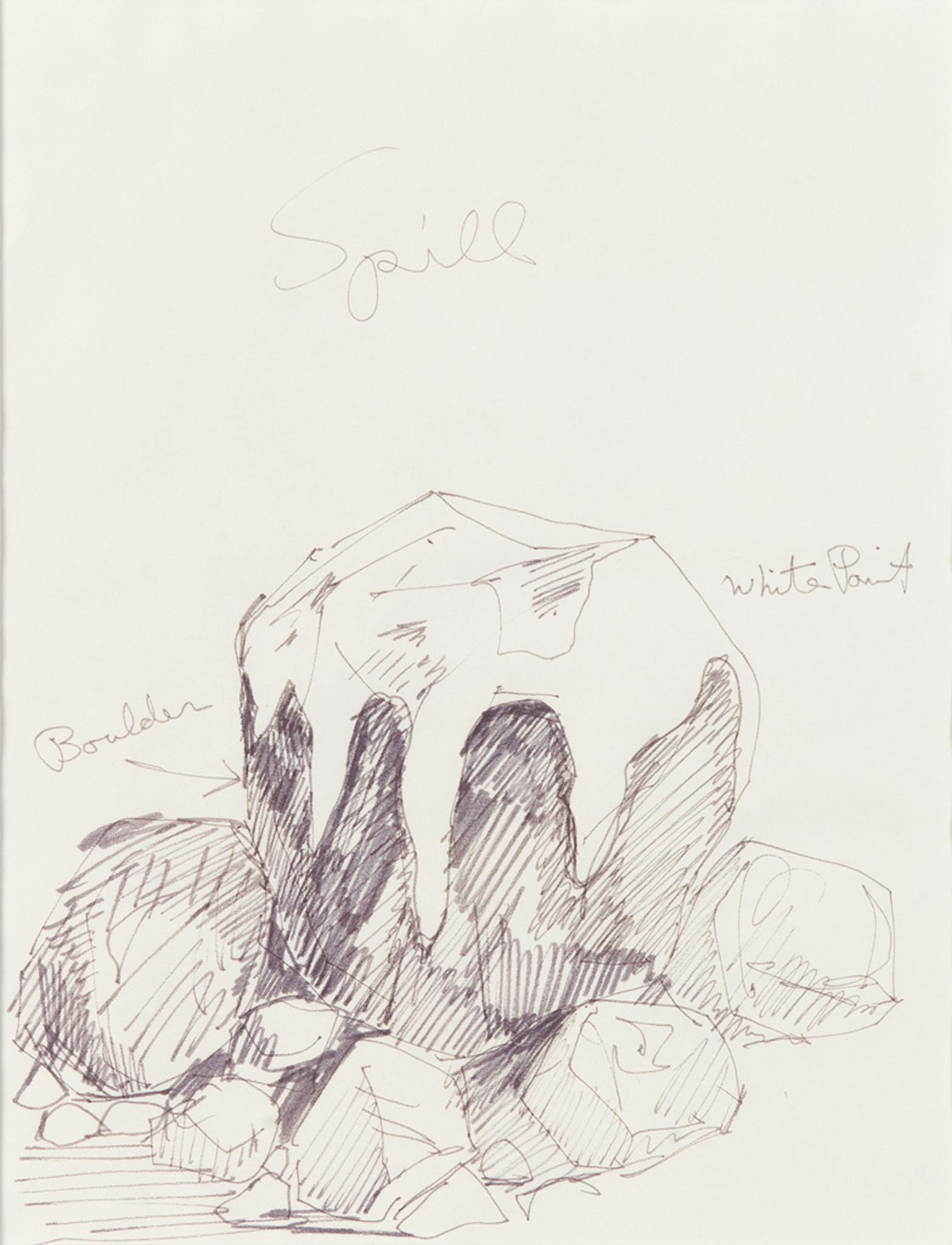

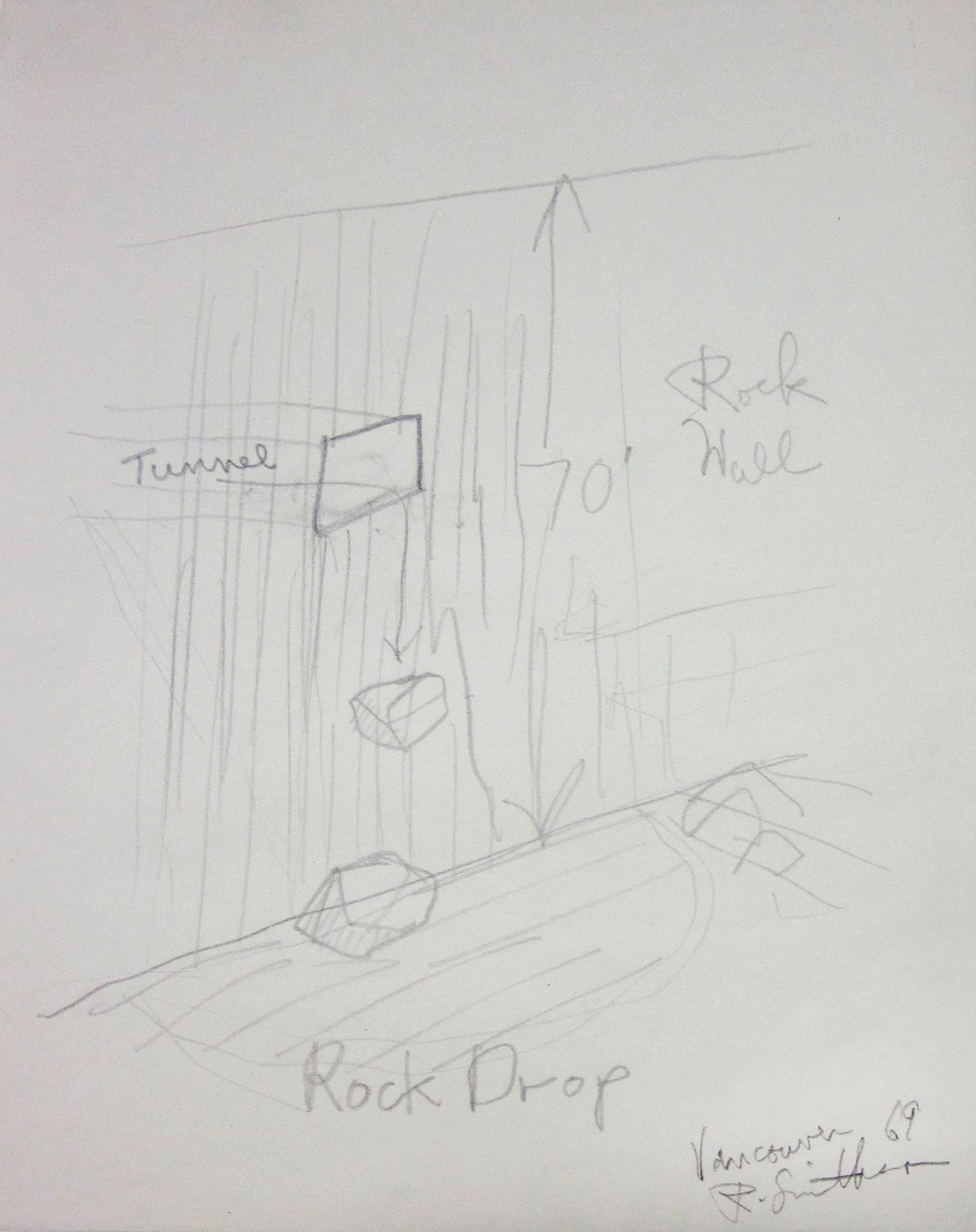

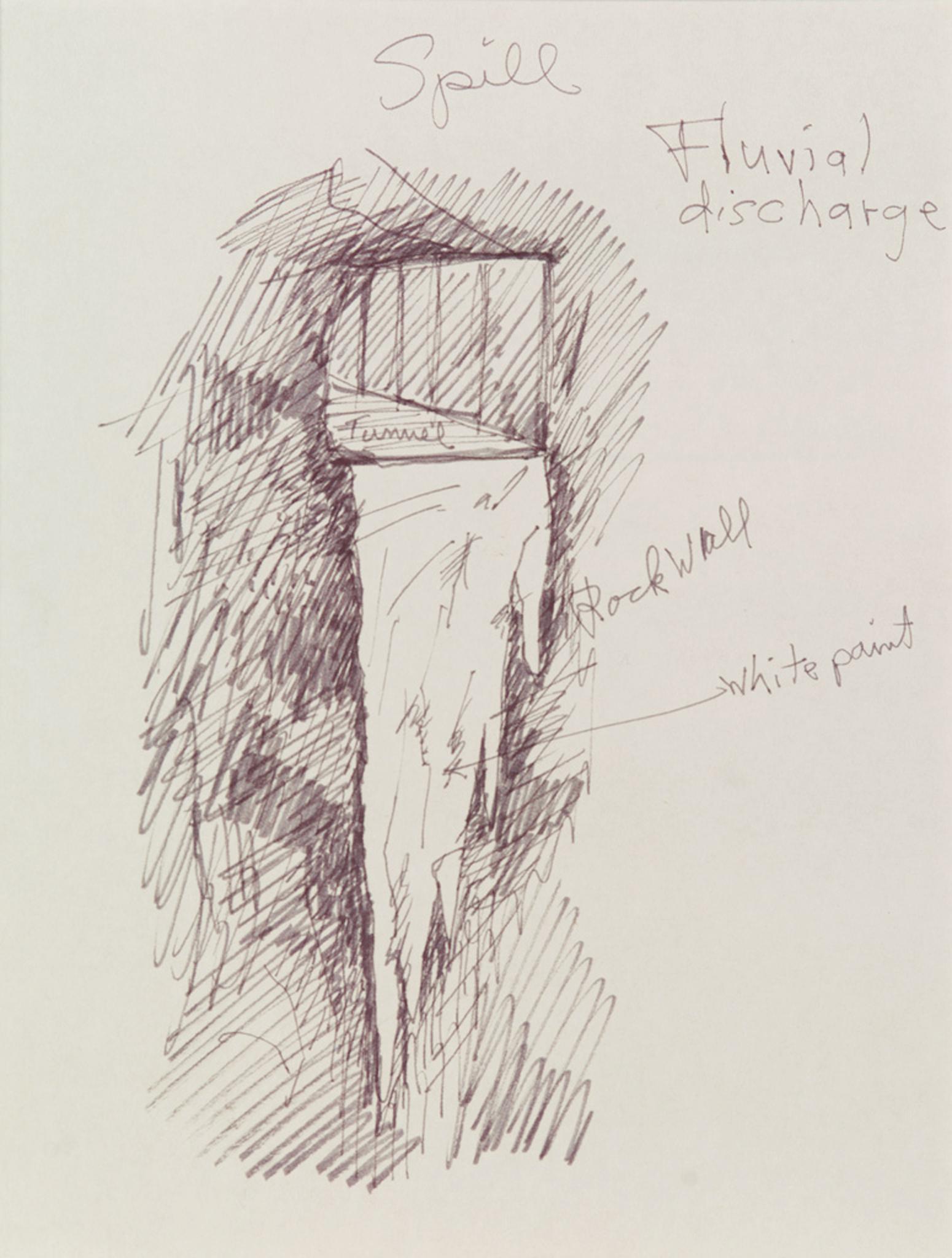

Smithson subsequently produced a series of drawings at Britannia Beach. Like most of Smithson’s chosen sites, the nearby Anaconda Copper Mine was going through its own entropic state.5 The artist planned to construct a cinema within the underground mine. The cinema screen was to be carved out of rock and painted white, and boulders would become theater seats.6 Although Smithson never followed through with his cinema proposal, it nonetheless played a deciding factor in his series of Britannia Beach drawings. The drawing Spill: Fluvial Discharge, along with another drawing in the series titled Rock Drop: (Britannia Beach Project), would have replayed the white paint on the cinema screen and the theater seats of rock as no longer contained material but as an entropic process. The same two drawings (with both materials exiting a rectangular opening at the end of a mining tunnel) explicitly associate a spill as both a fluvial discharge of manufactured white paint and falling boulders. In turn, a third drawing in the series, Spill: Boulder White Paint: (Britannia Beach Project) dialectically returns the process of dispersion performed in the other two drawings to processes contained or arrested processes. The drawing Spill: Boulder White Paint plays out another industrial spill mirroring nature’s own process, if one recognizes in the drawing a reference to the rock surface on Miami Islet that was splattered white with bird droppings.7 There was also the planned filming of the construction of the cinema. In describing his onsite experience, Smithson recalled “when one was at the end of the tunnel inside the mine, and looked back at the entrance, only a pinpoint of light was visible. One shot [Smithson] had in mind was to move slowly from the interior of the tunnel toward the entrance and end outside.”8 There is no way to know what might have transpired in the film’s shooting, but if the idea was to move from within the dark tunnel towards the light at the end of the horizontal tunnel and into the opening, it meant the culminating moment filmed would consist of blinding white light. It would represent maximum entropy—equilibrium—or a complete dispersal of Smithson’s entire Britannia Beach narrative.

Things went badly for Smithson with his Miami Islet proposal. In late January with a crane already anchored off Miami Islet and a truck load of glass on its way, the British Columbian government stopped the project and withdrew permission. Shortly thereafter the artist left Vancouver, took a side trip to create his most recognized earthwork, Spiral Jetty, and began a series of reclamation proposals for post-mining sites. But with reclamation legislation in the US dragging on until 1976, Smithson only ran into delays and, ultimately, rejections.

A half-century later, the forecast made in The Limits of Growth of the dire consequences of exponential growth in the extraction the earth’s resources have become reality. And if Smithson’s unfinished Britannia Beach project has anything to offer on the matter, then I will add this. In the midst of the everchanging anthropocenic state of the earth, and our ongoing refusal to recognize never-ending capitalist growth as a primary culprit, the artist’s project remains a reminder of what will continue, what with the existential necessity for radical changes in our economic relationship with the earth. As sustainable development begrudgingly happens by social design, it will be in the midst of an ongoing entropic collapse of the Holocene.

Selected Bibliography

Arnold, Grant. Robert Smithson in Vancouver: A fragment of a greater fragmentation. Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2004.

Flam, Jack, ed. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

Kevin Griffin, “Art Seen: From approval to rejection: before Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson proposed Glass Island by Nanaimo.” Vancouver Sun, (Vancouver, BC) April 5th-May 5th, 2016.

Smithson, Robert. “Four Conversations between Dennis Wheeler and Robert Smithson,” edited by Eva Schmidt. In Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, edited by Jack Flam, 196-233. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

About the Author

Ron Graziani is an art historian and associate professor at East Carolina University. Graziani holds a Ph.D. from UCLA. His Ph.D. is an interdisciplinary degree, in political science, aesthetic theory, and the field of psychoanalysis. Graziani has been invited to present his research at professional conferences (Art Institute of San Francisco, Harvard University, George Mason University). He has published in peer-reviewed journals (Critical Inquiry, Art Criticism) and authored a book at Cambridge University Press.

- 1On Dec 15 Smithson got approval for the project from Canada’s Deputy Minister, but Miami Islet would remain with the crown. Arnold Grant, Robert Smithson in Vancouver: A Fragment of a Greater Fragmentation. (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2004), 17.

- 2Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jorgen Randers, William Behrens lll, The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, (Universe Books: New York, 1972). The results were first presented at international conferences in 1971.

- 3Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jorgen Randers, The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update, (Chelsea Green Publishing: Hartford, VT, 2004).

- 4In 2021 Earth’s Overshoot Day was July 29. https://www.overshootday.org/.

- 5When the mine closed in 1974, the company did not clean up any of the chemical pollutants it had dumped over its history, despite the fact that acidic drainage at the site made it the worst point metal pollution in North America. As a result, it was remediation (not reclamation) that occurred at the site, which meant creating a national historical site and a museum that is now owned by the Britannia Beach Historical Society. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britannia_Mine_Museum.

- 6Smithson, Robert “A Cinematic Atopia (1971)” in The Collected Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Jack Flam (California: University of California Press, 1996), 142.

- 7Kevin Griffin, “Art Seen: From approval to rejection: before Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson proposed Glass Island by Nanaimo.” Vancouver Sun, (Vancouver, BC) April 5th-May 5th, 2016. https://vancouversun.com/news/staff-blogs/from-approval-to-rejection-before-spiral-jetty-robert-smithson-proposed-glass-island-by-nanaimo.

- 8Smithson, The Collected Writings, 142.

Graziani, Ron. "Britannia Beach Project." Holt/Smithson Foundation: Scholarly Texts Chapter 3 (February 2022). https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/britannia-beach-project.